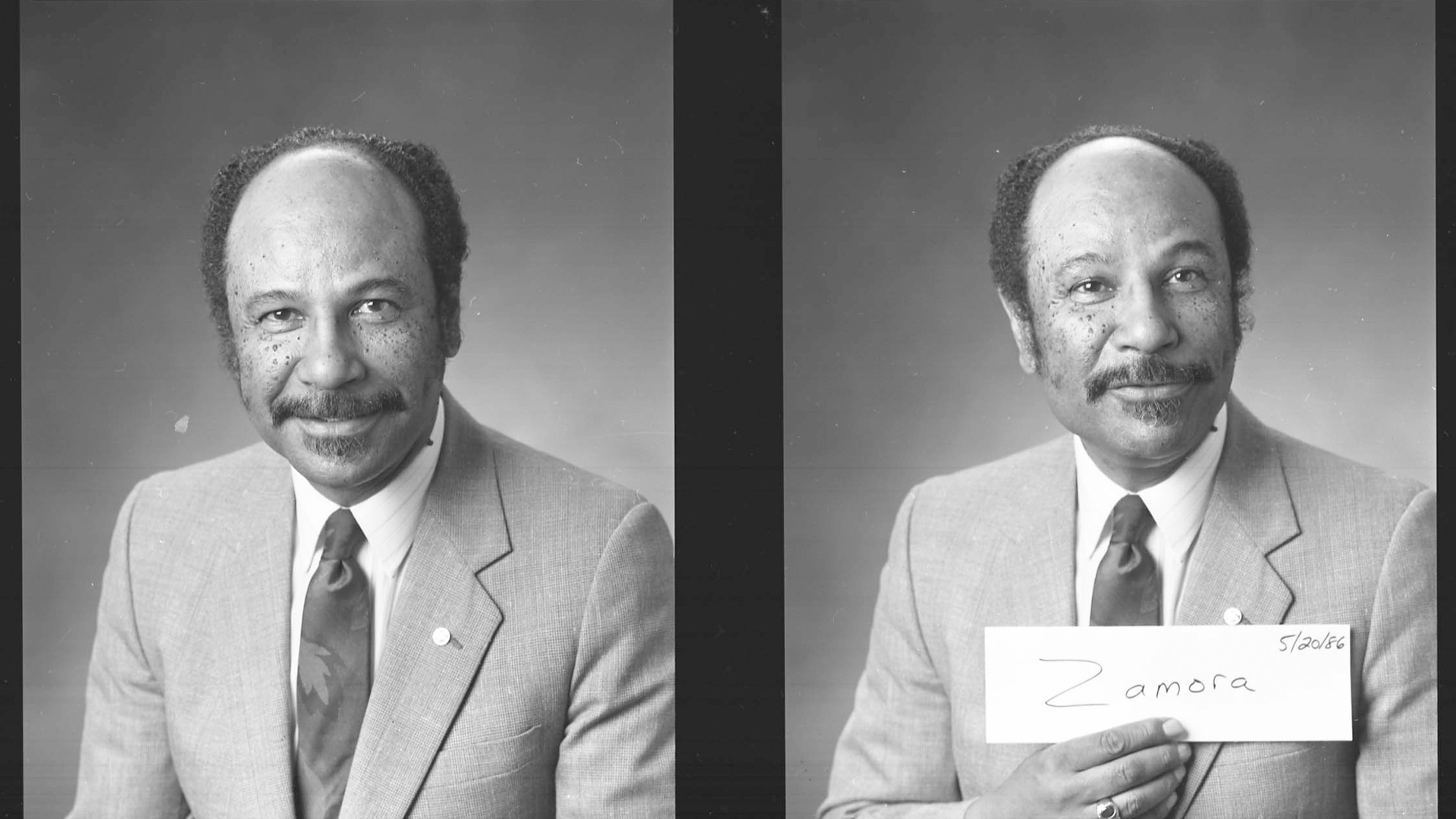

Tony Zamora: Purdue’s Renaissance man for 5 decades

Widely described as a friend, a mentor, a legend and an icon, Zamora served as director of the Black Cultural Center from 1973 to 1995 and retired as BCC director emeritus.

A determined driver and advocate of cultural and diversity programming. A persistent commitment to student success, human rights and the community’s arts scene. A tireless volunteer and supporter of service organizations, particularly youth programs in Indiana and Illinois. A lover of music, particularly jazz and that genre’s incredible power for connection and creativity.

“Mr. Zamora was an influential force on campus and was an advocate for Black student success,” says Renee Thomas, who succeeded Zamora at the BCC and remains its director. “I am forever grateful for his remarkable service over many years as director of the BCC. I will always remember the excellence Mr. Zamora demonstrated throughout his life and career at Purdue. As part of our 50th anniversary celebration in 2019, the BCC named the Antonio and Betty Zamora Performance Studio in his honor.”

Zamora died on July 2, 2020, after a courageous, 14-year battle against Parkinson Disease. He was 90.

During his 22-year tenure at the helm of the BCC, Zamora launched the Black Voices of Inspiration, a 100-member choir. He created the Jahari Dance Troupe, New Directional Players and the Haraka Writers, in addition to hosting many lectures and programs. He expanded the center’s library into a major collection of books, periodicals and videos with a focus on African American culture and history. In addition, he initiated an artist-in-residence program and led an effort to create a University scholarship named for Helen Bass Williams, Purdue’s first African American professor.

“He was an icon and a man of great stature, and his wisdom was often sought after by many of us. His was a singular good soul,” says Johnny Brown, a longtime Purdue mathematics professor. “He leaves us with good thoughts, many accomplishments, and, of course his great music.”

Zamora’s biggest thrill was coordinating the 1975 campus event that featured heavyweight boxing champion and Olympic gold medalist Muhammad Ali, who filled Elliott Hall of Music with spectators eager to hear the legend speak about friendship and other issues. In describing that event, Zamora told The Exponent in 2016 that Ali’s visit was “one of the most tremendous experiences” of his life.

Other luminaries Zamora brought to campus included Maya Angelou, Julian Bond, Dick Gregory, Gwendolyn Brooks and James Baldwin.

Speaking in connection with Zamora’s 1995 retirement celebration, then-Purdue political science professor Floyd Hayes III noted that Black cultural centers were fairly uncommon when Zamora arrived at Purdue in 1973. There was no blueprint to leading such a center here. “Without written scripts or scores, Tony employed an historical Africanist tradition of improvisation as a foundation for leading the BCC,” Hayes said in 1995.

“Tony Zamora’s contributions to the Black community and others extend well beyond the BCC,” Brown adds.

Tony invited many distinguished African-American activists, speakers, writers, athletes and entertainers, and he always welcomed the wider community to join us on campus to experience these events and, in many cases, meet these people. This helped to forge a close link between the town-and-gown Black community and beyond.

Johnny Brown

Challenges growing up in Chicago

Born on Feb. 16, 1930, Zamora was educated in Chicago and raised by a single mother, Aldonia F. Lewis. When Tony’s mother died when he was just 9 years old, loving foster parents Mr. and Mrs. Raymond Dennis raised him to adulthood. In the 1950s, he moved to Champaign, Illinois, where he met Betty Smith. They were married on July 16, 1959.

A widely respected saxophonist, Zamora formed jazz bands in Champaign. Living near the campus of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, he interacted with the music faculty and international students from Africa. Aided by a group of U of I students and the local American Federation of Musicians union, Zamora created a program to provide free music lessons and instruments for children in the community.

As his work became publicly known, Zamora was asked to be director of U of I’s African American Cultural Program, becoming its second director in 1970. Zamora, however, believed Illinois at that time was not committed to the program and resigned after just one year.

Zamora was selected as the third director of Purdue’s BCC when he arrived in 1973, just a few years after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and he quickly becoming a leader and mentor for Black Boilermakers. One student who found what he called a “home-away-from-home” at the BCC through Zamora was Joe Barry Carroll. Starting his Purdue career in 1976, Carroll studied economics, became an All-American basketball player, led Purdue to the NCAA Tournament Final Four, and was the top NBA draft pick in 1980.

“The center Tony developed was crucial for any student of color on campus. It was an oasis of nurturing,” Carroll, who played 10 seasons in the NBA, told the BCC. “Many of us came from environments totally different from Lafayette and West Lafayette. He was always looking out for us. He knew what we were up against, and he felt like it was his purpose to help us get through everything. I would go there to study. Also, when things came up, the annual controversy around race, the challenges of people coming from different cultures, he was there for us. He would have us covered. He would talk us out of our frustrations.”

After leading the BCC through the early days at its first location, Zamora retired in 1995. But he made sure of one thing before stepping away from the BCC — gaining assurance that the Purdue administration would follow through on his years-long effort for a new center. One of the most architecturally distinctive buildings on campus, BCC’s new home on Third and Russell streets was dedicated in 1999.

The BCC established the Antonio Zamora Endowment Fund to promote student leadership at the cultural center. While at the BCC, Zamora also showcased his talent with his Jazz Ensemble, making frequent appearances at the Taste of Tippecanoe Festival, the Riverfront Jazz and Blues Festival, Purdue Convocations and the Purdue Memorial Union Summer Concerts.

A legacy that lives on today

Zamora also created a series of free jazz concerts for Purdue and the surrounding community. A number of nationally famous musicians took part, including Ahmad Jamal, Phyllis Hyman, Patrice Rushen, Roy Merriweather and Freddie Hubbard. And his commitment to student success and jazz music lives on through the Tony Zamora Scholarship, an annual award given to Tippecanoe County high school students who share Zamora’s musical passions.

Brent Laidler, a Greater Lafayette musician and music instructor, first met Zamora 30 years ago when he trusted Laidler to be personal repairman for his prized instruments. In time, Zamora turned out to be more than just another customer to Laidler, who operates Brent’s Bench music shop. “Tony became a mentor and was very supportive — almost like a second father to me,” Laidler says. “He was everything I wanted to be growing up.”

In 2019, when the BCC renamed its multipurpose room the Antonio and Betty Zamora Performance Studio, the center partnered with the Art Museum of Greater Lafayette to host an exhibit featuring pieces from the Zamoras’ art collection. A complementary exhibit included works by Carroll, who was named trustee of the Antonio and Betty Zamora Trust of African Art, which covered more than 300 pieces. In opening the exhibit, Zamora highlighted why art was such an important part of the mission in his life.

“I feel that art is revolution, and any real education has to include art,” Zamora wrote. “It is as important to students of color matriculating at a major university as it is to all people of color as we navigate a larger world that sometimes treats us like foreigners in our own land. You just cannot plant students in what is essentially foreign to them and expect them to do well without nurturing their spirit. As people of color, we need our art and color to properly nourish our spirit, our soul in all places.”

Speaking to the current state of race relations in our nation and the protests in response to the civil and social unrest, Professor Brown says Zamora would have been a supporter of the movement, with an emphasis on healing. “His calm, deliberate, thoughtful demeanor would have been welcomed by all,” Brown says. “Because of his pure goodness and the way he lived his own life and treated others — all others — he was worthy of respect when you were in his presence.”