Boilermakers share dream of shaping America’s nuclear future

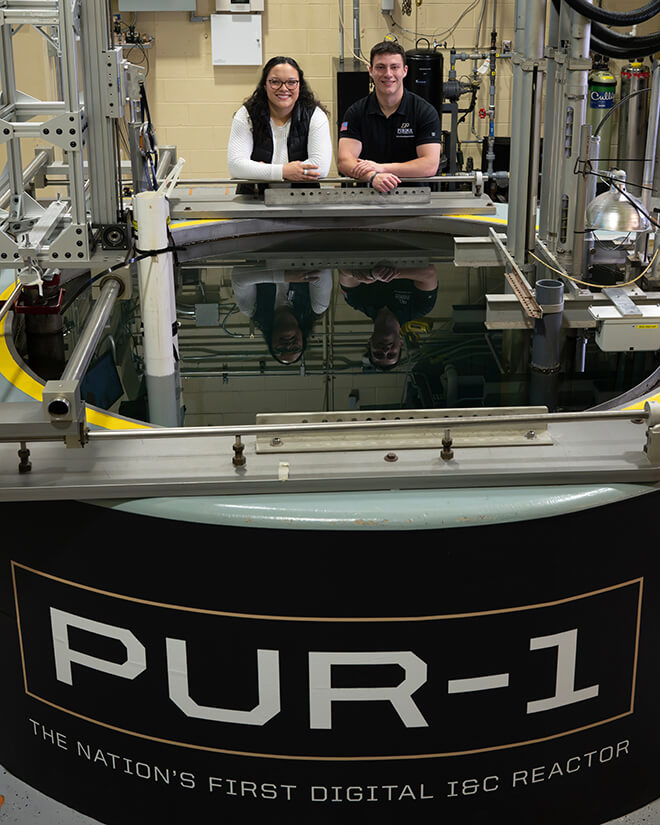

Purdue nuclear engineers Hannah Pike and Ryan Hogg have benefited from hands-on learning opportunities at unique facilities like PUR-1, the nation’s only all-digital nuclear reactor. (Purdue University photo/John Underwood)

No one in this high-tech world should live without a consistent flow of electric power to their homes.

However, that’s hardly the reality for millions of people across the globe. And it could become a nightmarish predicament even in the U.S. if new solutions to meet the exploding demand for electricity aren’t explored quickly enough.

Recent Purdue alum Ryan Hogg (MS nuclear engineering ’25) experienced firsthand the issues that an unreliable energy grid can create while on a family trip to visit his grandparents in Johannesburg during high school. Rolling blackouts created all sorts of inconveniences that changed how the family approached home life, whether it meant timing showers for when they’d have access to hot water or reducing the number of times they opened the refrigerator to prevent its contents from spoiling.

“You noticed things that you had never noticed before,” says Hogg, a U.S. Navy pilot who has observed similar issues with inconsistent power on other international trips.

It motivated Hogg to contribute to the re-emergence of an existing, but perhaps not fully tapped, power source — nuclear energy — that has the potential to satisfy the world’s growing needs. That motivation brought the 2024 U.S. Naval Academy graduate to Purdue, where a cooperative effort between the Navy and the Purdue Military Research Institute helped him complete a master’s degree in nuclear engineering in 18 months and then return to full-time military service.

His background as a nuclear engineer makes him something of a unicorn among Navy pilots.

“I might be the only one,” he says with a laugh. “I’m the only one I’ve ever met.”

‘I don’t think I could do this anywhere else’

Like Hogg, Purdue PhD student Hannah Pike (BS aeronautical and astronautical engineering ’23, MS nuclear engineering ’25) dreams of influencing the future of nuclear engineering — only she plans to go about it in a very different way.

A former captain of the World’s Largest Drum crew in the Purdue “All-American” Marching Band, Pike plans to become a college professor and continue her research that examines integrating AI and machine learning into nuclear operations.

Pike joined a research project with Purdue’s SCALE program during her junior year that convinced her to pursue a future in nuclear engineering. As a graduate student, opportunities to serve as a teaching assistant and as a research mentor for SCALE convinced her that this future would involve research and training the next generation of nuclear engineers.

Her research, which uses AI and machine learning to gauge radiation levels throughout nuclear facilities, has the potential to improve nuclear safety while taking measurements that humans can’t take.

“As I started working on my project, I became very interested in the topic, and I don’t think I could have this experience anywhere else,” Pike says. “Just thinking about where that research is going to go is very exciting.”

The interdisciplinary nature of nuclear engineering is another aspect of the field that appeals to Pike, who came to Purdue planning to someday become a NASA engineer.

“My interest in nuclear started when I learned about nuclear propulsion and potentially using nuclear energy to power rockets or something further down the line,” she says. “But then I learned that it also applies to agricultural engineering, has strong ties for electrical engineering and even mechanical. It just kind of interested me how it could relate to so many different disciplines. I could tell that nuclear engineering was one of those degrees where you could really make a big impact in a lot of different ways.”

I don’t think I could have this experience anywhere else. Just thinking about where that research is going to go is very exciting.

Hannah Pike

Nuclear engineering doctoral student, on her research that investigates AI and machine learning applications in nuclear reactor operations

Purdue’s unique features

There are many reasons why Hogg and Pike elected to pursue graduate studies in Purdue’s highly ranked nuclear engineering program.

They view nuclear facilities — particularly small modular reactors (SMRs), which are smaller, easier to build and less expensive than traditional nuclear power plants — as the obvious choice to meet America’s energy needs. And they have benefited from Purdue’s unique portfolio and focus on this emerging technology that continues to evolve.

The university comes equipped with essential facilities to create solutions and meet the demand for a nuclear workforce that will need to nearly quadruple in size by 2050, according to U.S. Department of Energy projections. Those facilities include PUR-1, the nation’s only all-digital nuclear reactor, and the Purdue University Multidimensional Integral Test Assembly facility, which is being revitalized for SMR research, education and training.

PUR-1 is the only nuclear reactor in Indiana, and its digital controls and operations enable research that is not possible anywhere else in the U.S. And because of its limited capacity — it generates power equivalent to that of approximately 10 microwaves — Boilermaker students can gain useful hands-on experience in a relatively low-stakes environment.

“Coming from a school, at Navy, where we didn’t have that research nuclear reactor readily available for education, maybe I have a different appreciation for it than the people at Purdue who have always had it,” says Hogg, who completed a mechanical engineering degree at the Naval Academy. “Now it’s not just, ‘OK, the teacher told me I was right, so I know my chart is right and my graph is right.’ Now I can see it in real life and say, ‘We were close, but were we close enough for what real life should be?’ We’re making assumptions all the time, but it’s hard to prove those assumptions until we actually see it in person.”

Influencing the future

While the Boilermaker engineers have grand visions about how they can contribute to the nation’s nuclear future, they will not have to wait for some far-off date to make a significant impact within their chosen field. They’ve already done it, having contributed to an influential Purdue-led study that proposed using SMR technology to meet Indiana’s spiking energy needs and drive economic activity.

Hogg, Pike and fellow grad student William Richards were among the collaborators who visited the Indiana Statehouse to hear legislators deliberate on how to effectively add nuclear to the state’s energy portfolio, and they were unanimously thrilled by what they heard.

“It was very exciting to see that something I did was reaching out to so many different people, and they were actually using it to form opinions and viewpoints on nuclear issues,” Pike says. “Those who referenced our report really did use it to justify how right now is the time for nuclear to come to Indiana because it is the future of energy.”

The process is only beginning, however.

Hogg points out that an increased emphasis on nuclear power will introduce an array of regulatory, logistical, geopolitical and safety complications that will not be easy to solve. And yet he remains motivated to ensure that energy challenges will not prevent the U.S. from enjoying a bright, tech-driven future.

“Having that power would increase productivity as a whole for society,” Hogg says. “But to stifle it so early and then to change our minds later and say, ‘We actually do need power,’ it would be more than five years before we can get it up and running. I think that’s why we need advocates now: to prevent future issues from arising.”

Having that power would increase productivity as a whole for society. But to stifle it so early and then to change our minds later and say, ‘We actually do need power,’ it would be more than five years before we can get it up and running. I think that’s why we need advocates now: to prevent future issues from arising.”

Ryan Hogg

MS nuclear engineering ’25