After harrowing escape from Afghanistan, Purdue instructor brings her family to West Lafayette

While instructor and family endured unthinkable circumstances back home, colleagues at Purdue rallied to support their fresh start in America

With gunfire echoing all around them, Mariam (last name withheld) linked arms with her brother, Razeq, and sister, Fahima, as they waded through the massive crowd that had gathered outside the gates of the Kabul airport.

“The shells of bullets, they were like rain coming toward us from everywhere,” says Mariam, a native Afghan who was suddenly far removed from the life she built in West Lafayette as a language and culture lecturer at Purdue University.

This was the third consecutive day that Mariam had traveled to the airport in her hometown, attempting to catch a return flight to the United States and her job at Purdue. Like the previous two days, the streets were packed with frightened citizens attempting to flee after the Taliban re-entered Afghanistan’s capital city and U.S. military forces prepared to exit the country.

Some members of the crowd pushed and shoved violently, causing Mariam and her siblings to worry about their parents, Hayatuallah and Hameeda, who joined them in delivering Mariam to the airport. Eventually, however, a wave of momentum carried the five family members up against an entry gate, creating the opportunity they had sought for seven chaotic hours.

Fortunately, two U.S. soldiers stationed inside the gate noticed Mariam waving her passport within the sea of humanity.

“They said, ‘Let her come.’ So, we went there and we were able some to get to the gate and enter.” Mariam says.

The five family members didn’t know it at the time, but those steps inside the airport gate were their first in what would become a 50-day journey to West Lafayette. After brief stops at various military installations on their way to the U.S., Mariam’s family spent six weeks living in a tent at Fort Bliss — an Army base on the Texas-New Mexico border — alongside thousands of other Afghan refugees before gaining entry to the country.

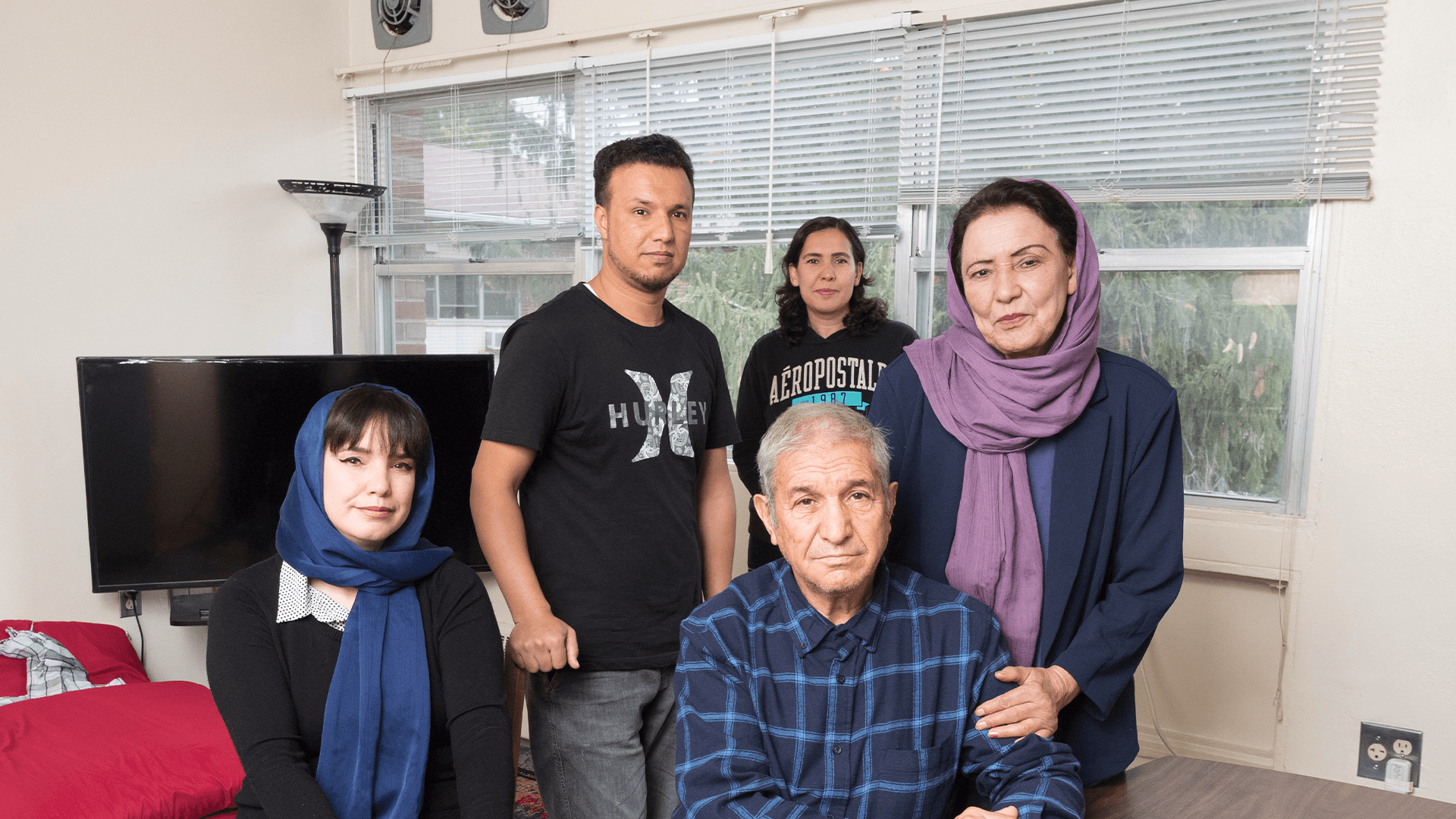

With support from Mariam’s Purdue colleagues and many other members of Greater Lafayette, the family finally arrived in West Lafayette in October to start over in America. Mariam hopes this is where they will choose to remain.

“They are new here, so they haven’t made their decision yet, but that’s what I want for them because I think that in the past 40 years it never got stable in Afghanistan,” Mariam says. “I really want them to like it here and be able to live and work the way they want. One thing that I’ve learned about the U.S. is there is a lot of opportunity here.”

Quick decision to flee

Mariam’s parents and siblings did not initially accompany her to the airport with plans to flee. They made that spur-of-the-moment decision while they watched their homeland rapidly crumble as the Taliban swept back into power.

“The Taliban took over, and they started to make this situation very chaotic. People were very lost. They didn’t know what they were supposed to do,” Mariam says. “I think my siblings were in a similar situation. They were very lost and shocked by what happened. I think it was a very quick decision.”

They were well aware of the fundamentalist regime’s attitude toward highly educated women — especially those like Mariam who worked at and partnered with American universities — and had heard rumors that Taliban fighters were going house-to-house in Kabul City and abducting family members of those with U.S. ties.

With those fears weighing heavily into their decision, the family left behind all their belongings and even a freshly prepared meal on the counter as they departed for the airport. They also left Mariam’s three other siblings and their families, whose safety remains a pressing concern.

“I have been trying to find ways to help them to come here or at least help them get out of Afghanistan, but it has been so hard.

mariam

An unexpectedly long journey

It was concern for family that brought Mariam back to Afghanistan after residing in the U.S. for most of the last decade.

According to Afghan cultural tradition, it is improper to tell someone in a faraway locale that a family member is sick or the extent of their illness “because they don’t want you to be worrying about them,” Mariam says.

Mariam learned in June, however, that her father was seriously ill. She fully understood why Purdue colleague April Ginther advised against returning to Afghanistan, but she was concerned about her father, Hayatuallah, a Type 2 diabetic.

“April was really worried,” Mariam says, “because the Taliban started in the past two years to kill those who had really high education, those who were activists or trying to support women’s education or if they worked with foreigners or Americans.”

Mariam is all those things. She completed a master’s degree and a PhD in second language studies/English at Purdue and was the first woman from Kabul University to obtain a doctorate in English. She also had worked on projects funded by the U.S. government, assisting in Afghan women’s efforts to escape violence or pursue higher education.

Nonetheless, she learned upon returning to Afghanistan that her father had contracted a severe case of COVID-19 during a wave of the pandemic that ravaged the country. Alongside one of her brothers, a nurse, she helped attend to Hayatuallah as he fought for survival.

“There was a time that he got really, really sick and we just thought that we were losing him because he had high blood pressure and, with his diabetes, his glucose level was going up and down so quickly,” Mariam says.

Her father eventually recovered, but he had lost a significant amount of weight and struggled to walk more than a few feet at a time. While Mariam had initially traveled home with expectations that it would be a short trip, she decided to postpone her return flight while helping her father regain his health and mobility.

She rescheduled a flight back to the U.S. on Aug. 15, which turned out to be the worst possible day to have travel plans in Kabul.

In the days leading up to her flight, Mariam heard news that the Taliban had overtaken other Afghan cities. She searched for earlier flights out of the country but was unable to find anything. The Taliban re-entered Kabul the very same day she was scheduled to depart, and Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s regime soon made a stunning decision to escape rather than defend the capital city.

Mariam worried that she was stranded. Her colleagues back at Purdue were worried, too.

“Mariam texted me and told me that her flight had been canceled, and we started texting back and forth,” says Ginther, professor of English and director of Purdue’s Oral English Proficiency Program and the Purdue Language and Cultural Exchange (PLaCE). “I couldn’t figure out what was going on with her. It was very stressful just trying to figure out what was going on.”

Ginther tried to assist her friend and colleague by contacting the offices of U.S. Sen. Todd Young of Indiana and state Rep. Sheila Klinker. Both offices responded quickly, but there was only so much anyone could do at the time.

Ginther also reached out to longtime colleague Mike Brzezinski, Purdue’s dean of international programs, who sought assistance from many friends and professional acquaintances within the community.

“So many logistical issues had to be addressed, not only for Mariam and her family, but for thousands of people,” Brzezinski says. “The federal government was flying by the seat of its pants.”

In the middle of the chaos were Mariam and her family, who remained unsure of what would become of them even after making it inside the airport gates. The pushing and shoving persisted after they joined a long line of Afghans hoping to escape Taliban rule, and no one seemed to understand what was happening.

“We were just standing in the line, getting closer little by little, but it was very exhausting because we were just standing there all night, no sleep, nothing,” Mariam says.

Persisting through brutal heat and exhaustion, Mariam and her family stood in line for approximately 40 hours at the airport before finally boarding a U.S. military cargo plane that would evacuate hundreds of Afghan citizens to Dubai.

“It was a feeling of relief, of course. For sure,” Mariam says of finally departing Afghanistan on the evacuation flight. “But at that time, I would say that since we were in shock, I didn’t feel anything probably. When you get to the point that you have no energy, nothing, you just don’t feel anything anymore, at least for a while until you’ve recovered from that situation.”

Uncertainty at Fort Bliss

Their recovery was only beginning, and an unexpectedly lengthy stay at Fort Bliss didn’t help matters.

As a U.S. citizen, Mariam could have departed for West Lafayette upon returning stateside. She chose to stay with her family members, however, as they navigated the process of being granted humanitarian parole while at Fort Bliss.

A process that she expected to take approximately two weeks wound up taking closer to two months as military and immigration officials struggled to accommodate the flood of refugees.

“They were trying their best to help us as much as they could,” Mariam says of the soldiers at Fort Bliss. “Everything happened so quickly. They had to be prepared, and they weren’t prepared for this, but they were really, really nice.”

At the camp, Mariam became an invaluable resource to the facility’s soldiers, doctors and nurses. As a woman who could translate between English, Pashto and Farsi, she helped bridge cultural and communications gaps during medical examinations, meetings and information sessions.

They had a very limited number of female interpreters, especially in the clinics,” Mariam says. “There were a lot of women who didn’t feel comfortable going to the clinic and talking about certain sicknesses that they had, especially if they were pregnant and trying to talk to male interpreters or if they were taking (to the clinic) their kids that were girls. They weren’t feeling comfortable being examined with male interpreters in there.”

Even while living in a giant tent on a military base with roughly 30 other families, Mariam remained dedicated to her job at Purdue. She insisted on continuing to teach her courses remotely despite objections from Ginther, her boss and friend. Mariam even requested additional data from AT&T to ensure that the base’s spotty internet access would not prevent her from connecting with her students.

“I kept telling her, ‘You don’t have to teach. We’ll figure out something for you.’ She was like, ‘Well I can do it!’” Ginther says with a chuckle. “And I thought, ‘OK, OK. Maybe it’ll make her feel better.’ But I thought, ‘Why is she teaching?’”

For Mariam, the answer was simple. She had a job to do, and she was determined to meet her obligations.

“They were really worried about me, but one thing that is really good about me is that I’m a very responsible person,” Mariam says. “I feel bad if I don’t do my job. So, this is a habit that I’ve had since my childhood. I always do my work no matter what, so I just told them that it was fine and I could manage it. And so, I did it.”

Eventually, the coordinating bodies sorted out the logistical issues that kept Mariam and her family at Fort Bliss for so long. Her family members would be allowed to join her in Indiana.

It was welcome news that Mariam would be able to bring her family home to the Purdue community, but she also was reluctant to leave behind the refugees in the camp who relied on her guidance.

“Even on that day I was leaving the camp, it was kind of a bittersweet moment,” Mariam says. “The people in that tent were mostly like, ‘You speak on behalf of us’ whenever something would happen. And when they needed help, they would come to me and ask me to help with it. So, I think that’s why I stayed for so long.”

Assistance from the Purdue community

Once Mariam and her family were bound for the U.S., Purdue colleagues Brzezinski and Ginther began coordinating efforts to help them start over in Greater Lafayette.

Mariam already had an apartment on campus but attempting to squeeze the entire family into a single unit would not have been an ideal housing arrangement. Brzezinski contacted a longtime acquaintance, Mike Shettle, director of administration at University Residences, to help locate a second apartment.

Shettle was eventually able to offer an apartment in the same building as Mariam’s. Brzezinski mobilized support from his home church, Calvary Church, and two other local houses of worship — Covenant Church and Faith Church East — to provide six months of rent support as the family gets on its feet.

Brzezinski reached out to Jeff Love, account vice president at Purdue Federal Credit Union, for help establishing a bank account — the Family Afghan Refugees Fund — where the family can accept financial donations from the community.

And he also helped address transportation, education and entertainment needs by arranging free CityBus passes; language tutoring for Mariam’s brother and sister, courtesy of Crosswalk Commons, a ministry of Kossuth Street Baptist Church; and tickets to a Purdue basketball game from Purdue Athletics.

“I’m grateful that many people in our community have been willing to give of their time and resources to help this family,” Brzezinski says. “Living here as long as I have, I know a lot of people, so I was able to make many ‘asks’ for assistance. I didn’t have any hard sells, to be quite honest.”

I’m grateful that many people in our community have been willing to give of their time and resources to help this family.

Mike Brzezinski

Dean, international programs

Meanwhile, Ginther and her colleagues from PLaCE began gathering furniture and other basics the family would need, such as food, phones, computers and gift cards.

“I’m proud of the community we have, so I know if she needs something, I can ask them and they will give it to me. And I know that’s true going forward, too,” Ginther says of her Purdue colleagues. “But I think that support for Mariam needs to be shared broadly and for an extended period of time to be fully effective.”

Amy Anthony, Calvary Church’s director of missions and outreach, also did her part after Brzezinski sought her assistance in furnishing the apartment where Mariam’s parents now reside.

Anthony admits she initially planned to purchase items that might fit comfortably in a traditional American living room, only to learn that Mariam’s parents would prefer to sit on the floor rather than on a sofa. Instead, she happily supplied a new rug and six red Japanese sleeping mats — fold-up mats similar to futon mattresses — for their living room.

“I loved being able to help with a very unique request like that, something that would be able to make them feel just a teeny sliver of home, because I can’t even imagine what it would be like to be suddenly displaced from everything I know and thrown into a completely different culture,” Anthony says. “I moved here from Canada and even that was a big adjustment.”

In fact, Anthony was pleased to have gained insight on typical Afghan home life. She has already heard that other churches in Greater Lafayette plan to sponsor some of the thousands of Afghan refugee families still awaiting assistance. Now she will be better prepared to help accommodate the new residents’ physical needs if asked.

The missions pastor adds that it will be just as important to have other Afghan families settle in the area to satisfy the refugees’ emotional needs.

“There will be a lot of emotional and spiritual and relational benefits to being able to meet with other people who have gone through some similar situations. I think it would be very difficult to be the only Afghan refugee family here,” Anthony says. “Hopefully whether it’s a year down the road or two years down the road, they’re building relationships and feeling accepted and welcomed into our community, but also at the same time being able to connect with other Afghan families who are coming and building relationships with them, as well.”

For now, Mariam’s family members are settling into their new surroundings and hoping that those they left behind will remain safe until they are able to reunite outside of Afghanistan.

Still feeling both relieved and exhausted after surviving a traumatic return to and escape from her home country, Mariam takes comfort in the presence of the family members who already made it here and the assistance they continue to receive while restarting their lives in an unfamiliar place.

“All my colleagues, they have been helping a lot, so I am really overwhelmed — especially Mike and April, who went above and beyond to help and support me and my family during those difficult times,” Mariam says. “April has always been my role model since I took her class and got to know her.

“To be honest, when you see that people care so much about you and they’re supportive, whatever you go through, you start to forget about (what you went through). So, it was really nice to have so much support. I’m really proud to be part of this community.”

How you can help

- Purdue Federal Credit Union

Purdue Federal Credit Union has opened an account, the Family Afghan Refugee Fund, to accept donations on the family’s behalf. Checks can be made out to that fund name and dropped off at any Purdue Federal branch office. Purdue Federal Credit Union account holders also can transfer funds to this account in person or over the phone, but not via online banking. - Purdue Language and Cultural Exchange

- Purdue International Programs