Welcoming women engineers to Purdue

Four women who have served as director of Purdue’s Women in Engineering Program pose with Leah Jamieson, center, the university’s John A. Edwardson Dean of Engineering from 2006-17. From left to right are Donna Frohreich McKenzie, Beth Holloway, Jamieson, Jane Zimmer Daniels and Marie McKee. In 2018, Purdue renamed the program’s directorship in Jamieson’s honor. (Photo by Vincent Walter, courtesy of Women in Engineering Program)

Founded in 1969, the Women in Engineering Program was the first of its kind

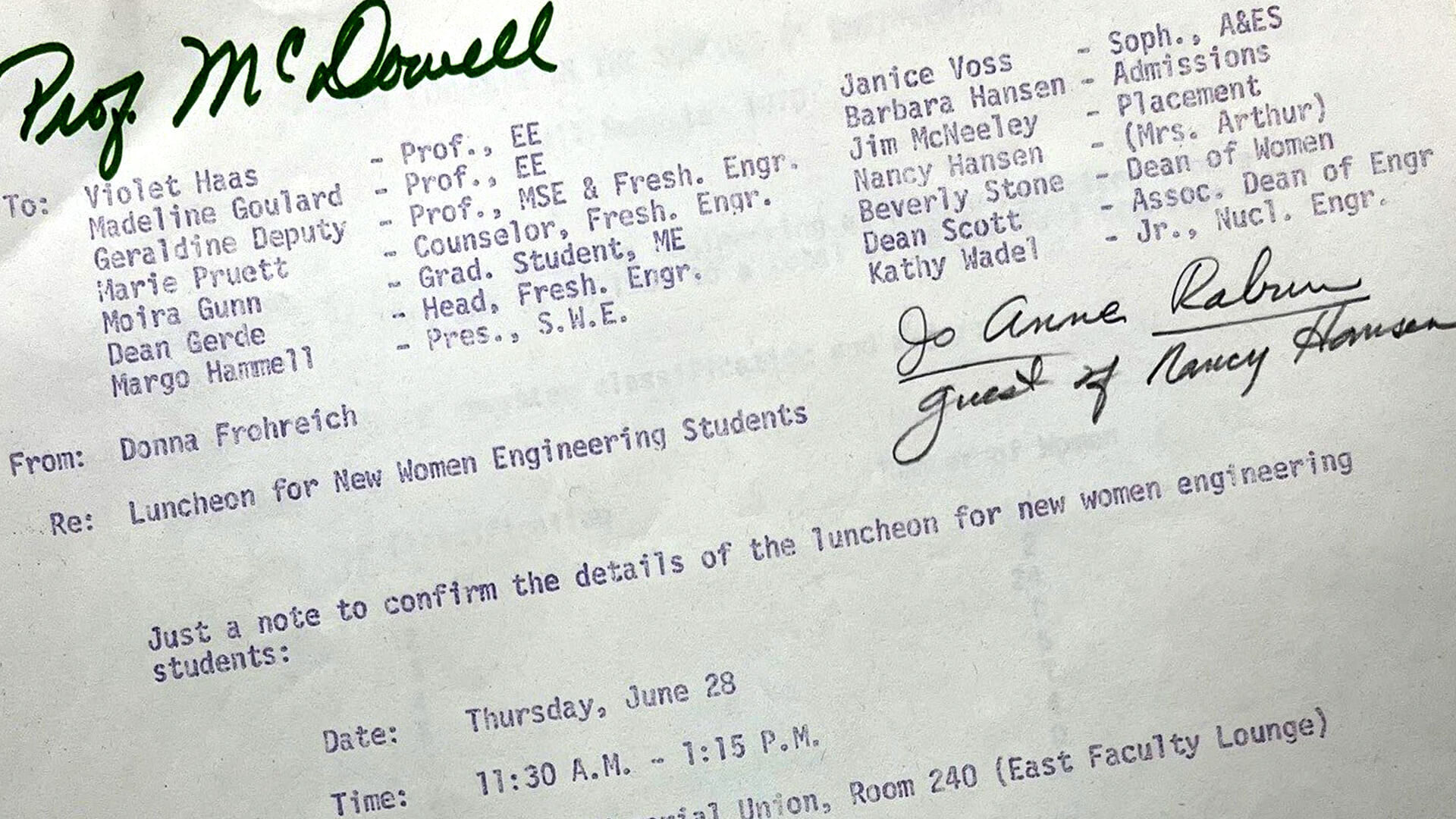

Beth Holloway was cleaning out her desk recently when she came across an old memo that caught her attention.

Holloway, the Leah H. Jamieson Director of Purdue’s Women in Engineering Program, quickly realized that she had found a document that provided valuable historical insight into her organization, the College of Engineering and the university itself.

At first glance, the 1973 memo from Donna Frohreich McKenzie, the Women in Engineering Program’s founding director, looked like a basic invitation to a luncheon for incoming female students. But then Holloway scanned the list of recipients and noticed multiple names that would stand out to anyone with a passing knowledge of Purdue’s history.

Among the faculty, staff and friends who would be in attendance:

- Violet Haas, one of Purdue’s first female engineering professors, for whom the university named an award presented annually to individuals, programs or departments that facilitate the advancement of women.

- Beverley Stone, dean of women and future dean of students, who was a beloved campus leader and strong advocate for Purdue women.

- Nancy Hansen, wife of the student-oriented Arthur G. Hansen, who championed diversity in 11 years as Purdue’s president.

And among the student hosts, two women who rank among Purdue’s most prominent engineering alumnae:

- Janice Voss, then a sophomore studying engineering science, who went on to log nearly 19 million miles circling Earth as the first female astronaut who graduated from Purdue.

- Moira Gunn, then en route to becoming Purdue’s first female PhD recipient in mechanical engineering, who went on to work at NASA and host tech-centric programming on National Public Radio.

In the note to this list of influential Boilermakers and influencers-to-be, Frohreich McKenzie explained her objective in terms that might shock a current student.

“The purpose of the luncheon is to make these new students feel welcome at the university and to indicate to their parents that we feel that engineering is a very appropriate, acceptable career for women!” she wrote. “Many parents seem to disapprove of their daughters studying engineering – too ‘unfeminine.’”

That dismissive attitude was all too prevalent in those days, which was a primary reason why many of the Boilermakers listed on the memo supported creating the nation’s first collegiate Women in Engineering Program in 1969.

At the time, women made up less than 1% of Purdue’s engineering enrollment. And even if these women engineers showed the fortitude to stick it out and earn a degree, they would enter a profession where they would be lucky to land a job interview, much less a position where they would be granted access to the plant floor.

“It wasn’t just their experience in school that was hard for those women,” Holloway says. “It was the entire span of their experience in engineering from start to finish.”

Carrying on the Purdue legacy

Like the culture at large, Purdue had plenty of room to grow when it came to equal treatment of women students in engineering and other disciplines. However, Holloway – herself a Purdue engineering graduate, as are her husband, Eric, and twin children Riley and Reese – is nonetheless grateful that some Boilermakers identified the disparity and worked to provide a more equitable environment for all.

“It makes me incredibly grateful to know that there were people then who did those things, not because they had to, not because it was a popular thing to do, but because it was the right thing to do and they wanted to support students,” Holloway says. “I think that is part of who we are as a College of Engineering. That is part of our DNA, part of our history, part of our culture – that we always have people within the college who are doing things to support our students because it’s the right thing to do.

Supporting students is what allows them to grow and develop into the engineers, the leaders of tomorrow they are destined to be, and carry with them part of our Purdue legacy.

Beth Holloway

Leah H. Jamieson Director, Women in Engineering Program

“Supporting students is what allows them to grow and develop into the engineers, the leaders of tomorrow they are destined to be, and carry with them part of our Purdue legacy.”

That legacy dates back to Purdue’s founding in 1869, when Indiana Gov. Conrad Baker signed a bill creating the state’s new land-grant university in Tippecanoe County.

Initiated by the federal Morrill Act of 1862, land-grant institutions threw open the doors of higher education to the everyday Americans that the system had previously ignored. The commitment to provide educational opportunity to all has inspired countless changes for the better at Purdue.

Two significant changes occurred in 1935, when Purdue President Edward C. Elliott hired world-famous pilot Amelia Earhart as a career counselor for women and advisor in aeronautics and Lillian Gilbreth as the nation’s first female engineering professor.

“That was pretty forward-thinking,” Holloway says. “And so, I think the establishment of a Women in Engineering Program was built on those foundations.”

However, the Women in Engineering Program is not Purdue’s first organization created to provide support and community to the university’s women engineers. Founded in 1954, the Purdue Society of Women Engineers is the nation’s oldest continuously chartered SWE student section. The organization originated at Purdue in 1947 as the Gamma Chapter of Pi Omicron before changing its name seven years later to the Society of Women Engineers, Purdue Student Section.

Other organizations that supported underrepresented engineering student constituencies would follow. In 1974, the founding chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers and the Minority Engineering Program launched at Purdue, providing support for exceptional students like Destiny White to blaze trails in their chosen engineering disciplines. And in 1984, Purdue students created the first social sorority for engineers, Phi Sigma Rho, now a national organization.

Holloway believes it’s hardly coincidental that these organizations – each of which has served as a model program that many others have emulated – came into existence at Purdue. It was all in keeping with the founding mission.

“I do think that any school with a land-grant mission needs to understand who they’re trying to serve and who they’re not serving and try to understand why that is and make some special efforts in those areas,” Holloway says. “Whether it’s women in engineering or underrepresented minority students in any field of study or first-generation students, I think our land-grant mission really needs us to focus on underserved populations. That is the ideal of the land grant: to serve the people who didn’t have access.”

Our land-grant mission really needs us to focus on underserved populations. That is the ideal of the land grant: to serve the people who didn’t have access.

Beth Holloway Leah H. Jamieson Director, Women in Engineering Program

Getting results

In its earliest days, the Women in Engineering Program focused on a basic mission of supporting women students who were working to adapt to – and choosing to remain in – an environment where women were frequently an afterthought. For example, one of Frohreich McKenzie’s first projects as director was to create a map of the restrooms available to women in Purdue’s engineering buildings.

The Women in Engineering Program still adheres to the original mission (minus the map of restrooms), but the scope of its work has greatly expanded:

- Beyond providing community and sharing information on careers and companies, its outreach and current student programming inspires and connects thousands of students annually from kindergarten all the way through graduate school.

- It created Purdue’s first learning community (originally in Earhart Hall and now in Meredith Hall South), where first-year engineering residents can socialize and easily form study groups with neighbors who are enrolled in the same curriculum.

- It offers two courses – Women in Engineering Seminar and Gender in the Workplace – that bring in dynamic speakers and share realistic perspectives on what to expect within the profession.

- And it provides a wealth of tutoring, mentorship and networking opportunities, including access to some of the 13,000-plus women who have earned engineering degrees at Purdue.

The results have been nothing short of remarkable. While there were only 47 women enrolled in engineering at Purdue in 1969, there were 817 by 1977, according to research published by William K. LeBold, a prominent Purdue freshman engineering professor and administrator from 1962-2002.

By the time Holloway succeeded longtime Women in Engineering Program director Jane Zimmer Daniels in 2001, the number had increased to 1,472. And the exponential increases have only continued.

As of fall 2022, there were 4,193 women engineering students at Purdue, with women making up 26% of the combined undergraduate and graduate engineering enrollment. In addition, 32% of first-year engineering enrollees were women, Purdue’s highest-ever percentage of incoming women engineering students.

Driving such improvements has been a primary objective of Holloway’s two decades leading the Women in Engineering Program, and thousands of women have benefited – including her own daughter. Before graduating from Purdue’s Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering last spring, Riley Holloway took advantage of multiple opportunities to network and build her engineering skills, working for seven semesters in biomedical engineering professor Craig Goergen’s Cardiovascular Imaging Research Laboratory and participating in experiential education opportunities like EPICS, BME Ambassadors and, yes, the Women in Engineering Program.

“[At the Women in Engineering Program], I got a sense of belonging, so I liked that aspect of attending Purdue,” Riley said last year in a College of Engineering feature story about the winning senior design projects that she and her brother, Reese, helped create in their respective engineering majors.

While Holloway is quick to point out that there is still much work to be done, she can’t help but appreciate how much things have changed in the half-century since Frohreich McKenzie authored the memo she recently discovered in her desk drawer.

Without the support of countless administrators, faculty, students, foundations, corporate partners and friends, Holloway says the Women in Engineering Program couldn’t have become the resounding success that it is today. And it all started with that core group of supporters who simply followed their conscience by helping an underserved group of students gain a better opportunity to succeed.

“I look back at those historical documents and think about the energy that it took to try to build the momentum that I enjoy now. That was a big lift,” Holloway says. “It may not have felt like it was a big deal to some of them, but for the organizers, to get people together to coalesce, to show that, yes, there are people at Purdue who want you, who want you to be successful, that was a big deal. And we reap the benefits of their efforts even today and are inspired by them to continue our support of students.”