Investigating the link between the gut microbiome and food insecurity

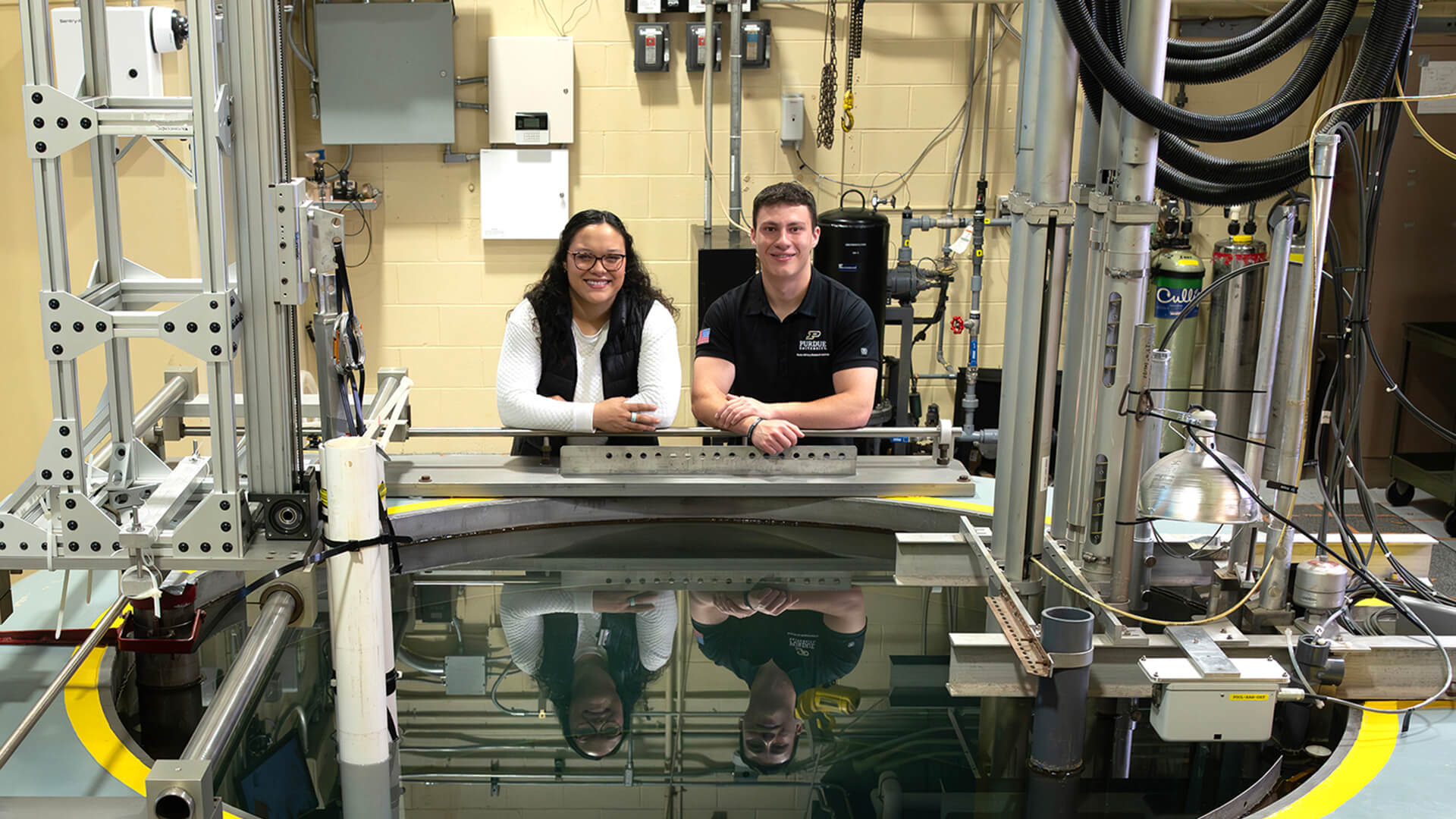

Patricia Wolf, assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition Science in Purdue’s College of Health and Human Sciences, investigates the relationship between food access, the gut microbiome and cancer risk. (Purdue University photo/Charles Jischke)

Purdue’s Patricia Wolf explores the relationship between food access and cancer risk

According to the Department of Agriculture, around 13.5 million U.S. households experienced food insecurity in 2021. Food insecurity is defined as the uncertainty of having or inability to acquire enough food to meet the needs of all household members due to insufficient money or other resources.

In college, Patricia Wolf experienced food insecurity firsthand. She worked a full-time job in a restaurant to make ends meet and, for most of her dinners, consumed the food diners left to be discarded.

“These experiences influenced my interest in researching how food insecurity might relate to health,” Wolf says. “As a society, we need to take care of the more vulnerable people in our communities.”

Wolf is a microbiologist and registered dietitian nutritionist. Today, as an assistant professor of nutrition science at Purdue University, she investigates the relationship between food access, the gut microbiome and cancer risk. Depending on an individual’s social and structural environment, they may lack access to nutritious, high-quality foods and ingest more processed foods. Wolf stresses that not all processed foods are bad and that there are different levels of food processing. Much of the food we eat is processed to some degree, but how those additives affect the bacteria in our gut is still relatively unknown.

“I’m interested in how the environment you’re exposed to impacts the bacteria in your gut in a variety of ways,” Wolf says. “If you have lack of access to high-quality foods, does that lead you to eat foods with added nutrients? And do those additives get metabolized by gut microbes, leading to colorectal cancer? How does food access relate to other health inequities? These are the questions I’m trying to answer.”

As a land-grant university, Purdue values what I value in my research, which is translating the science to the broader community and addressing inequities in public health.

Patricia Wolf

Assistant professor of nutrition science

Individuals facing barriers to food access make choices based on what is available. A food environment index for a specific neighborhood assesses the types of stores in the area, such as grocery stores, convenience stores or bodegas. Understanding the food environment within a community is one aspect of Wolf’s research, but the actual food environment and the perceived food environment could be different.

“There may be other barriers that prevent individuals from accessing available food, such as economic constraints or feelings of safety,” Wolf says. “If you have a long bus ride to get to the store, that may impact what kinds of fresh foods you purchase because it will take too long to transport raw meat on the bus.”

Wolf also hopes to conduct a dietary intervention study to determine whether consuming more or less of a particular nutrient affects gut microbes and associated markers of inflammation. She’s also interested in how exposure to a dietary-related illness might relate to inequities. She’s part of the Microbes and Social Equity working group, which formed in 2019 to examine, publicize and promote a research program on the reciprocal impact of social inequality and microbiomes.

“It’s important for bench scientists like me to partner with social scientists and community partners who can implement programs or influence public health policy based on research findings,” Wolf says. “The first step is identifying the microbial mechanisms of disease, but then those findings need to be communicated to benefit the populations we are trying to serve.

“As a land-grant university, Purdue values what I value in my research, which is translating the science to the broader community and addressing inequities in public health.”

If you have lack of access to high-quality foods, does that lead you to eat foods with added nutrients? And do those additives get metabolized by gut microbes, leading to colorectal cancer? How does food access relate to other health inequities? These are the questions I’m trying to answer.

Patricia Wolf Assistant professor of nutrition science