Examining the role culture plays in medical distrust

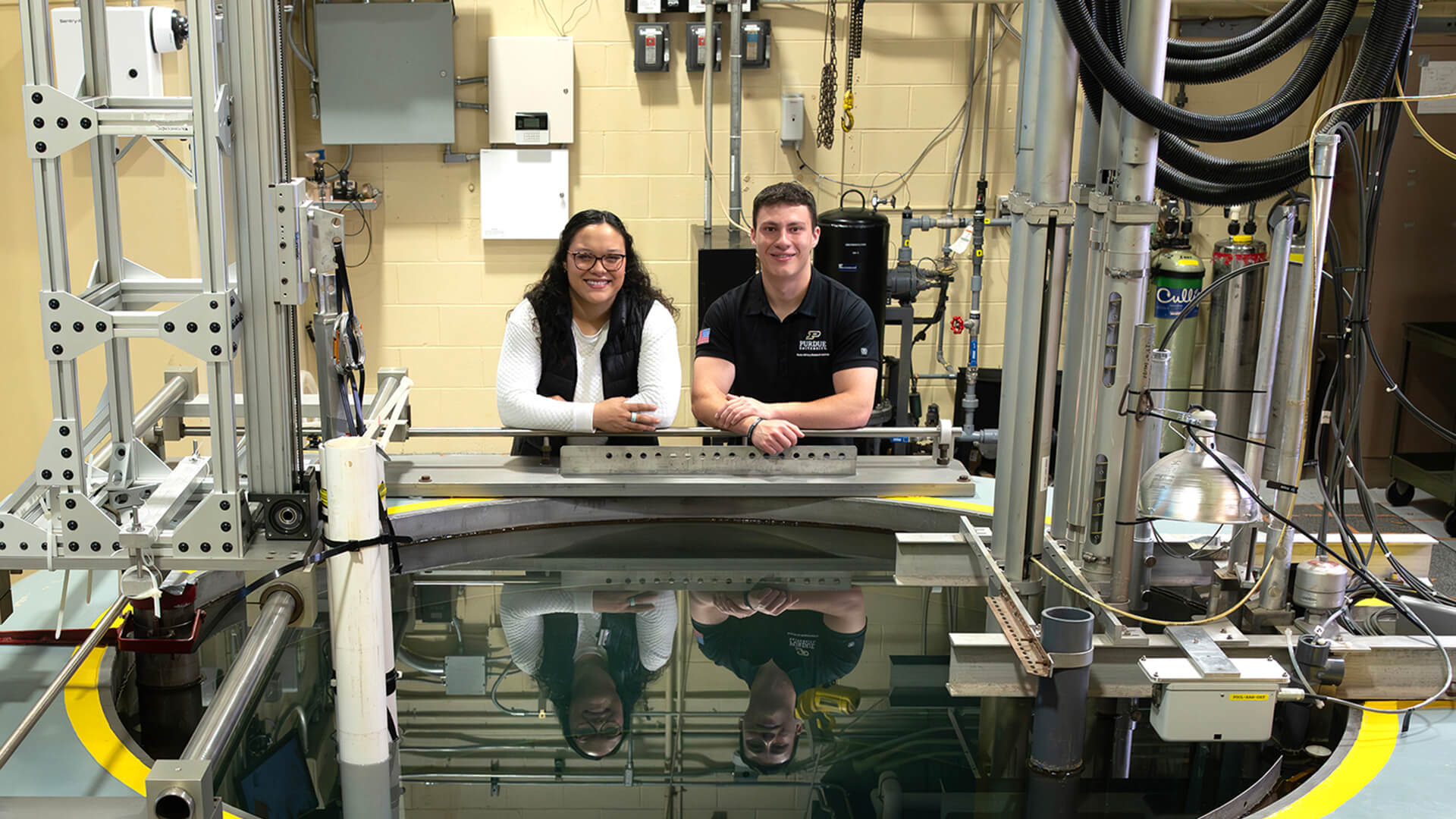

Carlos Mahaffey, assistant professor in the Department of Public Health, works to address historical trauma by reducing stigma and medical misinformation among Black Americans. (Photo by Charles Jischke for Purdue University)

Purdue’s Carlos Mahaffey develops intervention programs to address HIV disparities

Carlos Mahaffey grew up knowing about the Tuskegee syphilis study, in which researchers did not obtain informed consent from the 600 Black male participants who were denied penicillin even after it became widely available. The study went on for 40 years as its participants, primarily sharecroppers who had never previously sought medical care, experienced severe health problems including blindness, mental impairment and death.

For many Black Americans, the serious ethical issues that arose from the experiment created a legacy of mistrust in the medical community.

“I was raised in Columbus, Georgia, just one hour from Tuskegee,” Mahaffey says. “Most of the parents in the neighborhood told their children what happened there. As kids, we understood that culturally, there was a deep mistrust of the health system and government.”

Mahaffey, an assistant professor in the Department of Public Health in Purdue University’s College of Health and Human Sciences, researches the systems and conditions that perpetuate health and racial disparities, impact sexual behavior and promote health equity. His experience developing health intervention and promotion programs with marginalized communities has included projects with youth and adult correctional facilities, state government agencies and metropolitan and rural communities.

“In my work with correctional health and HIV disparities, I’ve noticed similarities to the syphilis study, where it seemed a lot of research was being done to communities, especially when working with people who are incarcerated,” Mahaffey says. “Incarcerated individuals don’t have as many rights and privileges or the benefit of knowing someone is looking after their best interests. Culture plays a big role in that, which is why it is critical to have a researcher who looks like you and understands the cultural nuances of your background.”

Mahaffey’s research focuses on HIV disparities in Black men who have sex with men (BMSM), a population disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS in the United States. Some of his participants may be married to women or identify as straight. Focusing on sexual behavior and not sexual orientation can help make individuals more receptive to information such as the availability of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis). PrEP can significantly reduce the risk of contracting HIV from sex, yet BMSM are less likely to take PrEP.

We have to be very careful working with marginalized communities that are vulnerable, systematically disadvantaged, and have a distrust in the health care system based on historical injustices.

Carlos Mahaffey

Assistant professor of public health

“Despite all the information we have about how to practice safe sex, there’s a disconnect somewhere, and I believe it has to do with culture,” Mahaffey says. “We have to be very careful working with marginalized communities that are vulnerable, systematically disadvantaged, and have a distrust in the health care system based on historical injustices.”

When talking with participants, Mahaffey’s goal isn’t to get everyone on PrEP, but rather to make sure they know it is available as an option and encourage them to discuss their sexual health with their medical providers. Again, trust can be a barrier to open dialogue.

“I chose to work in public health because I wanted to help dispel myths and make sure there are faces like mine in the field,” Mahaffey says. “When I’m talking to members of my community, they feel like they have someone to trust and we can build that trust back together.”

Mahaffey wanted to join the faculty at Purdue in part because of the collaborative group of scholars from across disciplines working to advance sexual health and address sexuality-related health inequities in the Sexual Health Research Lab. He was also attracted to Purdue because of the actionable items established by the university’s Equity Task Force to diversify its faculty.

“There was a huge shift in academia after George Floyd’s death and the resulting protests,” Mahaffey says. “A lot of institutions created DEI committees, but Purdue came out and said, ‘Here’s what we learned, and here’s what we’re going to do about it.’ Purdue has been very intentional about wanting to implement change.

“It’s a very exciting time to be a part of this change and collectively make an impact in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the world.”

I chose to work in public health because I wanted to help dispel myths and make sure there are faces like mine in the field.

Carlos Mahaffey Assistant professor of public health