Advocating for self and community

Dr. Michelle Ludwig’s hearing service dog, Pam, is one of the resources Dr. Ludwig relies on to navigate the world as someone with hearing loss. (Photo courtesy of Chris Kittredge Photography)

Since childhood, Purdue Pharmacy alumna with hearing loss has learned to navigate her own education – with help from Purdue

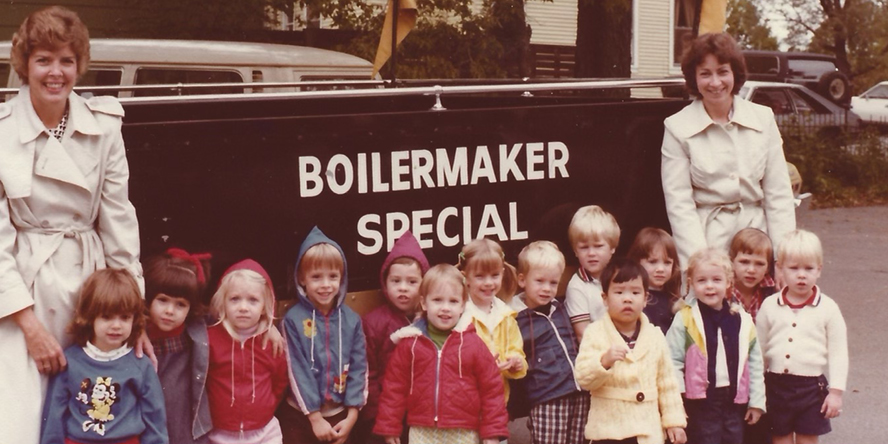

When Michelle Ludwig (BS pharmaceutical science ’00) lost her hearing at 2 years old due to pneumococcal meningitis, she also lost her ability to maintain her balance. She not only had to relearn how to communicate with others without the majority of her hearing, but she also had to relearn how to walk, run and do all the activities of an active 2-year-old.

“With the level of hearing loss that I had, it was called ‘profoundly deaf.’ This means I am at the most severe that you can have and still be able to have enough residual hearing for a hearing aid to help,” she says. “With hearing aids, the only thing I can hear is the vowel sounds. So, if I can’t lip-read everything in between the vowel sounds, I have to put it together, which is like doing a crossword puzzle all the time.”

Along with most of her hearing, Ludwig also lost the use of her vestibular system, which is the part of the inner ear that tells you instantly if you are off-balance. This meant she had to rely on other, slower systems the body uses to find its balance, like vision.

But she was not alone when it came to learning alternative ways to communicate and balance. She was able to work with specialists who helped her through the transition, teaching her about lipreading, how to read context clues to aid in communication, how to use technology alongside her hearing aids and more.

She considers herself fortunate to have grown up in West Lafayette, Indiana, just a stone’s throw away from Purdue and its audiology department in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences.

“I owe a lot to the Purdue audiology department,” she says. “They were instrumental in helping me learn how to adapt.”

In Ludwig’s experience, at the time, children with disabilities were not often placed in the public school system, and IEPs (individualized education plans) were not as common. The opportunity to work with Purdue experts allowed her to stay in the public school system, utilizing available technology to work with her teachers and learn how to thrive in a classroom environment.

Supported by Purdue

Ludwig had always been interested in medicine, but she was unsure if she would be able to attend medical school.

“At that time, the environment really was not super open-minded about people with disabilities going to medical school,” she says.

So she decided to start out by enrolling at one of the country’s best pharmacy programs – Purdue’s College of Pharmacy. That way, whether or not she ended up in medical school, she would still be able to fulfill her dream of being able to use science and medicine to help people.

While at Purdue, she was able to work alongside the Office of the Dean of Students to get the help she needed for her classes. Today, students needing accommodations work with Purdue’s Disability Resource Center, which is part of Student Success Programs.

One of the resources available was a CART (computer-assisted real-time transcription) service, which is similar to having a court stenographer alongside you in class. The stenographer would type what the professor said, and the words would almost instantly appear onscreen.

This resource was extremely valuable because, although Ludwig can read lips, there are many factors that contribute to getting the most out of the classroom.

She says, “In order to lip-read, you have to be sitting right in the front row, but if you have a really big lecture hall, you might still be 50 feet away from the professor. At that distance, their mouth is very small. Or if you have a professor with a beard, or if they turn around to write on the board, or if you want to look down at your notes, all of that’s really hard.”

While at Purdue, she completed two summer programs at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, where she first fell in love with the field of oncology.

“That was my first experience with pharmacists really being integrated into the hospital care team and my first experience seeing how oncology is really a multidisciplinary specialty,” she says.

After graduating from Purdue in 2000 with a degree in pharmaceutical science and a minor in Spanish, Ludwig went on to medical school at Emory University, citing the excellent education she received from Purdue as part of what made her so successful.

“The confidence that I had from having taken all of those classes from one of the top schools in the country made the transition into medical school easier,” says Ludwig, who completed MD and master of public health degrees at Emory. “My (Purdue) biochemistry textbook was literally the same one that they used in medical school.”

Before Ludwig enrolled, Emory had never had a medical student with hearing loss. Emory relied on her to outline the accommodations she needed.

“Fortunately, because Purdue had prepared me for the technology I was using there, I was able to just give Emory a list of the adaptive technologies that I needed,” she says. “If I had not had that background from Purdue, they would not have been able to provide those resources for me.”

During medical school, Ludwig spent time rotating through different disciplines in oncology and found that she liked radiation oncology, which was an extremely competitive specialty.

“There’s a pretty high level of physics in addition to anatomy in radiation oncology,” she says. “You had to have pretty good grades to be able to do that, so I was set up for that because of my background at Purdue.”

The confidence that I had from having taken all of those classes from one of the top schools in the country made the transition into medical school easier.

Dr. Michelle Ludwig BS pharmaceutical science ’00

Advocating for her own needs

During her first few semesters at Purdue, Ludwig quickly learned what it would take to advocate for herself and for her own needs.

“Even though from a young age I was the one going to my own IEP meetings, and I was the one that had to tell my teachers what I needed, it was still intimidating to be at a new place and have this thing that makes you stick out,” she says. “But I started to realize that if I didn’t have these resources, the fatigue of having to pay attention would absolutely wear me out.

“I was exhausted when I started college and pharmacy school.”

When discussing what it takes to navigate the world with a disability, Ludwig references “Spoon Theory,” which she says is a beautifully articulated way of explaining something she experienced but didn’t understand at the time.

Spoon Theory was developed by writer Christine Miserandino while trying to explain to a friend what it’s like to live with a chronic disease. The theory suggests that individuals living with chronic illness or disability start every day with a set amount of energy – or spoons. Throughout the day, every time energy is needed to go about everyday life, one or more of those “spoons” is used up. For example, for someone living with chronic illness or disability, getting dressed, making breakfast and getting to work might take up three of the 12 theoretical spoons they have for that day. By the end of the day, if you are out of spoons, you no longer have the energy to do anything else for yourself.

“I think Spoon Theory is a nice way of expressing the fatigue that comes along with the extra work some people need to do,” Ludwig says. “I think for anybody that’s faced with a disability, you’re either persistent or you’re not going to be able to do anything you want to do because you have to troubleshoot so many different steps along the way. You have to just kind of learn how to do that, and that’s just an expected thing.”

Ludwig still uses a variety of resources in her everyday life and in her job to help mitigate the use of these “spoons,” including her hearing service dog, Pam.

“Having Pam has really helped improve aspects of my life,” she says. “If my husband isn’t home, I know she will wake me up when my alarm clock goes off or when someone knocks on the door.”

Pam also helps Ludwig at work, alerting her when her office phone rings or when someone approaches from behind.

“I sleep better,” she says. “Which is a minor thing, but before I had my first service dog before Pam, I would put my work pager in my pajamas, and I would not sleep well because I was worried I was going to miss a page. And after a week of not sleeping well, you just don’t feel good.”

Ludwig sits on the National Board of Canine Companions, the service-dog organization that provided Pam. Canine Companions is the oldest organization that specializes in service dogs, other than guide dogs, providing assistance to adults, children and veterans with disabilities.

“These dogs give you back a couple of spoons to be able to do what you want to do,” Ludwig says.

She also believes that getting a service dog forces you to confront your level of confidence about your disability.

“If you have a service dog, it’s pretty obvious that you have a disability,” she says. “It’s made me have to be open and vulnerable about my disability and how she helps me with it.”

Continuing Advocacy

Ludwig is currently an associate professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, where she teaches first-year medical students and treats patients with breast cancer and gynecologic cancer. She also participates in a mentorship program with the AMPHL (Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Losses).

Her time studying Spanish while at Purdue still helps her today, as she is able to read patients’ lips in Spanish as well as English.

“I can speak Spanish to my patients without having an interpreter. That has been really helpful for me because 65% of my patients speak Spanish as a first language,” she says. “If I didn’t speak Spanish, I probably couldn’t do my job because we use a phone interpreter, and I wouldn’t be able to hear what the interpreter says over the phone.”

She is also in the beginning stages of an exciting clinical trial for a topical treatment to reduce some of the negative effects of radiation on the skin during cancer treatments.

Ludwig says she has been able to refer to what she learned in her Purdue pharmacology classes on drug development, which has been instrumental in getting the treatment through FDA approvals and on to clinical trials. She is especially excited about the prospect of using this treatment on patients who normally wouldn’t be able to receive this kind of care.

“A lot of my patients are medically underserved patients, which are typically underrepresented in clinical trials. They often have worse side effects because they have challenges affording over the counter products to address their side effects, so I am excited about providing this clinical trial opportunity for my patients.”