2024 Tyler Trent Award recognizes trailblazing health advocate

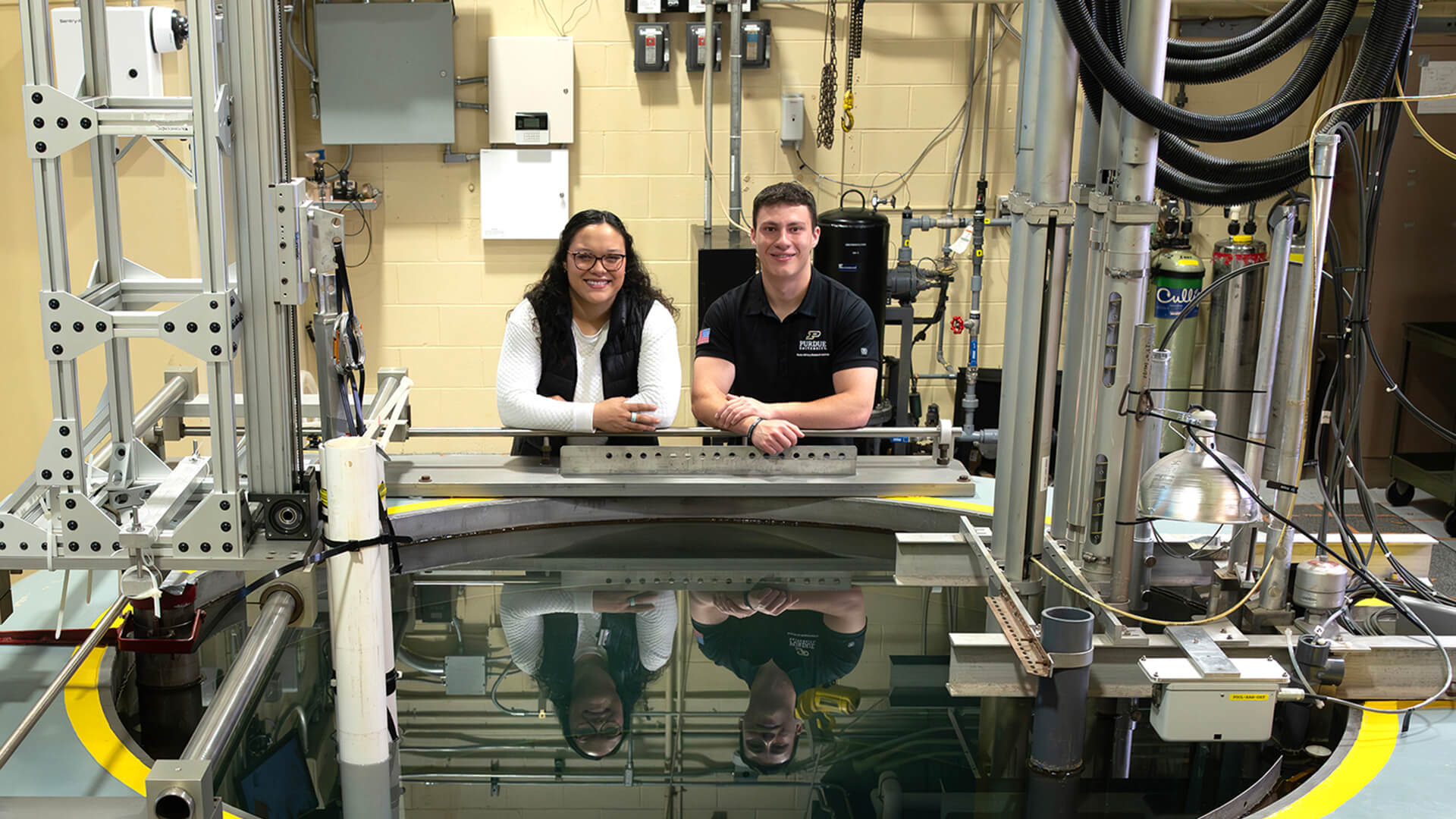

“Tyler’s story is incredible,” says Anneliese Williams. “He demonstrated a fight for life and was a strong advocate even in the face of hard circumstances.” (Purdue University photo/John Underwood)

Anneliese Williams raises awareness of accessibility concerns and patient care for the rare disease community

Overnight, Anneliese Williams went from playing sports as an active Purdue sophomore to lying immobile in an intensive care unit. She was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune condition that attacks the nervous system. Paralyzed from the neck down, she fell into isolation and uncertainty.

As COVID-19 restricted hospital visits, she battled the unexpected disorder without concrete causes or prognoses. Doctors tried to combat the Guillain-Barré complications, but the rare syndrome has no cure — only methods of slowing its progression and managing its symptoms.

Relying on breathing support to live, she realized she had to find a way to give herself hope. Alone, afraid and angry, she had to choose from three options. She could give up, fight physically but succumb to the sadness of her circumstances, or do her best to face the physical and emotional challenges of her diagnosis head-on.

I chose to hold on to who I am. And I think that’s what this award is all about: I refused to quit.

Anneliese Williams

Master of Public Health student

“I chose to hold on to who I am,” says Williams, the 2024 recipient of Purdue’s Tyler Trent Courage and Resilience Award. “And I think that’s what this award is all about: I refused to quit.”

The university honors Tyler Trent, a Boilermaker who embodied perseverance. Trent was a Purdue student and cancer activist who inspired the nation with his faith, drive and compassion. After his death in 2019, President Emeritus Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr., unveiled the Tyler Trent Memorial Gate and announced the Tyler Trent Courage and Resilience Award. Trent’s legacy is a permanent part of Purdue.

“Tyler Trent was the epitome of Boilermaker spirit,” says President Mung Chiang. “He breathed old gold and black and was such an inspiration to our community. It is exciting and fitting to recognize Anneliese Williams with this year’s Tyler Trent Courage and Resilience Award — a distinguished honor for those who never give up, who continue fighting in the face of adversity and for those who provide hope to others despite the incredible hardships they are enduring.”

“Tyler’s story is incredible,” Williams says. “He demonstrated a fight for life and was a strong advocate even in the face of hard circumstances. Being honored in this way is incredible.”

Bravery and dedication are principles Williams persistently promotes. She helped pass a bill in the Indiana General Assembly — while studying for her classes at Purdue and interning with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

“Now I know how much power each of us has,” she says. “Anyone can recognize a problem and realize that change is possible.”

Finding power during paralysis

When her parents suggested that she take a medical leave of absence from Purdue, Williams broke down in tears for the first time since her diagnosis.

“I didn’t want to lose my sense of being a Boilermaker,” she says. “Going to Purdue meant so much to me, and I told everyone I couldn’t leave. They thought I was crazy, but I kept up with two of my classes that semester.”

With nurses’ help, she listened to virtual lectures. As her condition improved, she dictated answers. But she wasn’t just passing classes. She was also forging an impressive path for the future, including interviewing for an internship with St. Jude.

“Toward the end of my time in the ICU, I had a virtual interview for this dream internship,” she says. “I was connected to a heart machine, and it kept beeping because of how anxious I was. I knew I had to try. I fought for my dreams and St. Jude said yes.”

Following a passion for advocacy

After being released from the ICU, Williams went to physical therapy — she regained some movement but now had to navigate life with a wheelchair. She became the first wheelchair user to intern in the St. Jude Pediatric Oncology Education program in its 20-plus years of existence.

During her internship, she discovered a career path that combines pediatric clinical practice with global medicine research. She still works with the team at St. Jude remotely while she pursues a combined master’s 4+1 program at Purdue.

Part of giving herself hope for the future was finding her voice and utilizing her experiences, which is where rare disease advocacy became a beacon. Williams also grew up with a rare form of vascular malformation and has a twin sister, Amelia, with a different rare disease diagnosis. Amelia was involved in the EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases, which advocates for life-changing national policies and access to diagnoses, treatments and cures.

Together, the Williams sisters became Young Adult Rare Representatives for the EveryLife Foundation and learned about rare disease advisory councils — statewide committees that better lives for the communities they represent. Indiana didn’t have a committee.

They started talking to councils in other states to identify what aspects of their legislation were successful. The more they learned, the more stakeholders they met, leading to them forming the Indiana Rare Coalition. The group — including representatives from hospitals, nonprofits and pharmaceutical companies — came together to advocate for House Bill 1201, which would formally establish the Indiana Rare Disease Advisory Council to address the needs of rare disease patients, caregivers and providers.

Williams testified in the Indiana House of Representatives and Senate health committees to help pass the bill.

“Find something you’re passionate about and you’ll make an amazing difference,” she says. “I was so shy, but when I found my voice, I was able to change legislation in Indiana.”

The council can now explore new directions for improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases in Indiana.

Continuing to create change

While working with St. Jude and the EveryLife Foundation, Williams has made headway for underrepresented students on campus.

“When I came back to Purdue as a wheelchair user, I realized how crucial accessibility is for everyone,” she says, “not just for those with physical disabilities, but for a diverse range of learning disabilities and barriers.”

She joined the Purdue Student Government’s Ad Hoc Committee on Disability and Inclusion and helped draft an action plan to address accessibility opportunities on campus.

Gradually, she’s been able to get back to what makes her happiest: being active. Along with wheelchair basketball, she’s found a sense of belonging at CrossFit West Lafayette, where the staff has worked with her to find ways to move.

Williams looks forward to learning about health equity in her classes and what it takes to develop public health interventions and theories. After graduating with a master’s degree, she’s interested in taking a gap year, then attending medical school and eventually conducting clinical practice and research.

“I’m grateful for the perspective I’ve gained,” she says. “You can’t change what happened in the past, but you can do your best to impact the future. I think that’s been powerful.”