What is a land-grant university?

Industrialist John Purdue committed $150,000 to Tippecanoe County’s successful bid to become the site of Indiana’s land-grant university. On May 6, 1869, the Indiana General Assembly officially established the new institution, calling it Purdue University. (Purdue University photo)

Teaching, research, service roles are pillars of the land-grant mission

Purdue University takes its status as a land-grant university seriously.

Type the university’s name into a Google search bar and you’ll see proof in the primary text that links to its homepage: “Purdue University – Indiana’s Land Grant University.”

But what does that mean exactly? What makes Purdue and its 111 land-grant peers – a who’s who of prestigious research universities that include Big Ten members Ohio State, Wisconsin, Michigan State, Illinois, Nebraska, Maryland, Minnesota, Rutgers and Penn State – different from other colleges and universities?

Why do initiatives like Purdue Global and Purdue Polytechnic High Schools (PPHS) fit into Purdue’s land-grant legacy and future?

If you’re a Purdue graduate or student, why should you take pride in the university’s land-grant tradition?

And if you have no connection to Purdue at all, why should you care that these universities even exist?

This is the second chapter in a four-part series that should help answer those questions, sharing why land-grant universities came into existence and how their creation produced countless benefits for the students they educate and the communities they serve.

Our first chapter focuses on Purdue’s tradition of educational opportunity, revealing how the intent behind new initiatives like Purdue Global, Purdue University Online and PPHS is no different from the spirit that drove the university in its earliest days. The remaining chapters will address activities that make Purdue unique among these universities and why flexibility will be important if land-grant institutions are to maintain their prominent position within academia and society.

By sharing these stories, we hope to reveal the through line connecting Purdue’s past to its present, influencing many of the decisions and discoveries that enabled its emergence as one of the nation’s top universities. The driving force is the land-grant directive to teach, conduct research and serve the state of Indiana and beyond.

If you’re a Boilermaker, much of what you love best about Purdue is likely related to this mission in one way or another. That’s why you should care.

Now let’s get to some of those questions:

Why were land-grant universities created?

Simply put, land-grant universities are problem solvers – a defining characteristic that ranks among the primary reasons these institutions were created. They were designed to give working-class Americans their first chance at a college education. And that’s only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to their impact.

When he first proposed land-grant legislation in the 1850s, U.S. Rep. Justin S. Morrill of Vermont aimed to “have learning more widely disseminated,” particularly in two primary areas: agriculture and the mechanic arts (engineering).

Morrill and his cohorts observed that American farming productivity lagged behind that of European countries that experienced great success by applying scientific learning to their work. In the same vein, the Civil War-era U.S. lacked a workforce with sufficient training to meet the long-term needs of an increasingly industrialized nation.

“Morrill said, ‘This country is expanding rapidly. We need engineers to build roads. We need engineers to build bridges. We need engineers to build and operate factories. We need people who understand science and agriculture,’” says John Norberg, a Purdue University historian who has written eight books about the university and its people.

The Morrill Act offered states an opportunity to sell plots of federal land, much of which had once been inhabited by Native American tribes. In order to increase U.S. agricultural and engineering expertise, proceeds from these land sales would help fund the creation of universities that emphasized these subjects, as well as military tactics and classical studies.

The universities the legislation spawned – many of which now rank among America’s top public research institutions – went on to surpass even Morrill’s ambitious initial vision through their unique commitment to teaching, research and community engagement.

How does extension make land-grant universities unique?

Land-grant universities distinguish themselves from other institutions by directing their collective brainpower and resources toward research that addresses society’s economic, political or social problems. Then they share what they learn with the public in an effort to identify workable solutions.

We were going to actually take all of (our) knowledge and deliberately extend the opportunity to use it, to learn it, to the whole state of Indiana. More broadly, to the people of the country.

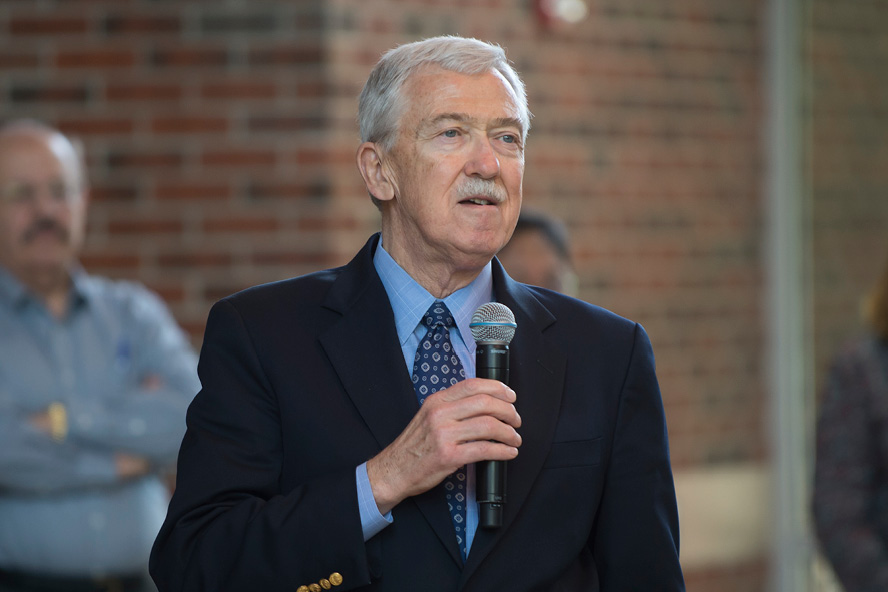

Martin Jischke Former Purdue president

“These universities would engage in extending their understanding of these basic and applied research topics, their capacity to teach both practical and liberal education, and extend the impact of the university beyond the students that came to the campuses, and beyond the research that was done by faculty with graduate students that ended up leading to research papers and new theories of how the world works,” says Martin C. Jischke, who as Purdue’s 10th president drove multiple landmark economic development and extension efforts.

“We were going to actually take all of that knowledge and deliberately extend the opportunity to use it, to learn it, to the whole state of Indiana. More broadly, to the people of the country.”

The extension mission was in some ways the most radical portion of the Morrill Act’s design, as it created the foundation for a system that tethered land-grant schools to their constituents. By sharing their expertise with those who could put it into practice, these universities built strong bonds with their communities that were difficult for those outside the land-grant system to replicate.

Additional legislation only strengthened the connection. The Hatch Act of 1887 granted federal funds for states to establish agricultural experiment stations operated by their land-grant institutions. And in 1914, the Smith-Lever Act created a system of cooperative extension services designed to inject land-grant universities’ expertise into communities throughout their states.

Purdue was ahead of the nation on this front, having conducted vital extension work as early as the 1880s. By 1893, Purdue Farmers’ Institutes and short-course training were benefiting Hoosiers in all 92 Indiana counties, establishing the statewide presence that Purdue Extension offices maintain today.

As was the case in most land-grant universities’ earliest days, their extension efforts remain heavily concentrated in agriculture. There are still enormous societal benefits associated with introducing drought-resistant crops; establishing best practices for livestock, fish and plant breeding; or digitally managing forests – just to name a few ways that Purdue’s College of Agriculture contributes to the general welfare.

In addition, land-grant universities’ modern-day extension work crosses disciplinary boundaries to address a wide range of societal needs. From promoting financial literacy and small-business growth to helping young citizens build leadership skills and healthier bodies, extension outlets quietly provide a wealth of cultural and economic resources that many citizens might not even associate with their state’s land-grant institution.

“All of that is helping people who don’t go to college and think that they aren’t impacted by universities at all, when, in fact, they are,” Norberg says.

How do the research and engagement pillars work in tandem?

Countless Purdue faculty and students have contributed to the university’s reputation as a center for basic research – focused on the advancement of knowledge – as well as applied research that aims to solve specific problems.

Their discoveries have helped surgeons identify malignant cancer cells and remove them during surgery. They’ve created complex organic molecules commonly used to manufacture anything from pharmaceuticals to electronics. They even contributed to Boilermaker astronaut Neil Armstrong’s giant leap: humankind’s first steps on the lunar surface.

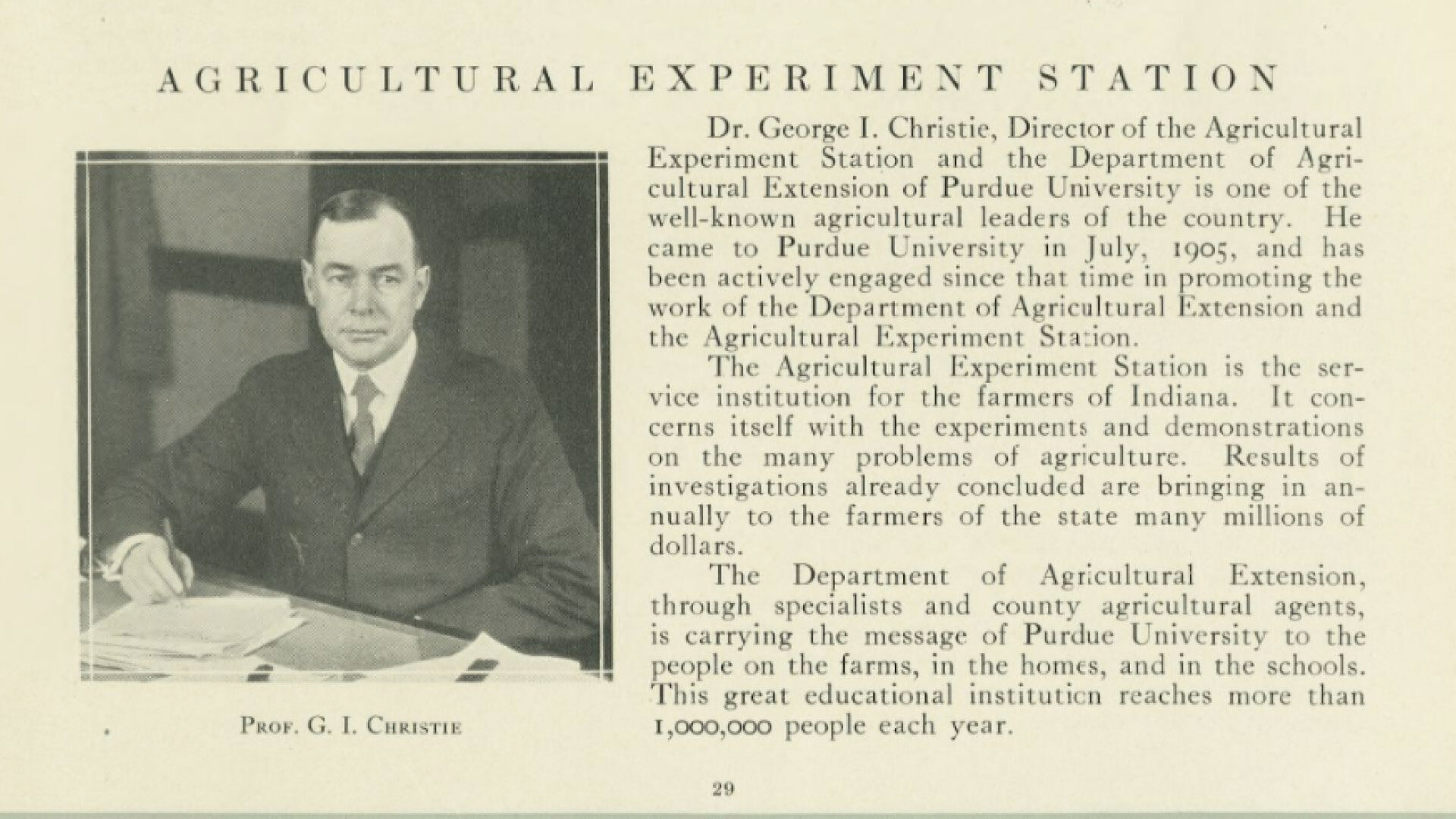

Their commitment to knowledge sharing dates back to Purdue’s early years, when George Christie, part-time showman and full-time director of Purdue’s Agricultural Experiment Station, would travel across Indiana, sharing information with those it would benefit most.

A 1909 article in the Indianapolis Star credited Christie and Purdue for Indiana’s increased interest in corn growing, noting that the state had “forged to the front as producer of the best corn in the world” as a result of those efforts.

“My colleagues two generations ahead of me in agronomy, they had exhibits and demonstrations on interurban trains,” says Victor Lechtenberg (PhD agronomy ’71), who joined the Purdue faculty after completing his PhD and later served as dean of agriculture, among other leadership positions. “They would go up and down the railroad in Indiana – and in the fall of the year after the harvest during the winter – and have short courses and one-day workshops and just a whole host of educational programs to try to teach farmers and inform them about the latest information coming out of the research programs at the university.”

The Agricultural Extension exhibit trains weren’t just for the farmers, adds author Angie Klink, who has written extensively about Purdue’s history. They also shared knowledge that would help homemakers in the communities they visited.

“During World War I and World War II, there was rationing going on. It was up to the extension agents to lead a national effort to go out and reeducate,” Klink says. “They’re trying to produce more wheat to send overseas to feed the troops, so that means rationing here and using less wheat. One of the slogans during World War I was, ‘Wheat will win the war.’ So, the women were taught by extension agents how to make potato bread or cornbread, how to use corn and potato rather than wheat because the wheat was so important.”

How has the research process changed?

As society evolved, so too did the partnerships that initiated many landmark research projects.

Research support frequently comes from government bodies like the National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense or National Science Foundation, but it just as likely might originate with an industry partner. The research might help that company provide a better product or service, or it might help the researcher build a business around their new creation. This development expanded land-grant universities’ economic impact and ushered in a new era of entrepreneurial research.

Some people say entrepreneurship shouldn’t be part of the land grant, but it absolutely should be because it’s how we make the biggest impact.

Karen Plaut

Glenn W. Sample Dean, Purdue College of Agriculture

At Purdue, the nonprofit Purdue Research Foundation helps manage and license Purdue’s intellectual property and assists in economic development and technology transfer.

“There’s more entrepreneurship now,” says Karen Plaut, Glenn W. Sample Dean of the College of Agriculture. “Before, it was more giving technology and ideas away because in society you could operate that way. Now, if you have a major innovation, you have to build it into a business to get it out to those it can benefit the most. Some people say entrepreneurship shouldn’t be part of the land grant, but it absolutely should be because it’s how we make the biggest impact.”

Indeed, corporate involvement is often an essential ingredient that helps translate innovation into practice, says George Wodicka, Vincent P. Reilly Professor in Purdue’s Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, who led the program for 23 years.

“Oftentimes, companies have substantial product development capabilities since they manufacture at scale. This is where we partner up,” Wodicka says. “There’s just a tremendous amount of back-and-forth collaboration that maybe wouldn’t be obvious yet is essential to bring discoveries to market. Land-grant institutions have an inherent translational edge over many other types of institutions. We’ve built a productive academic-industry ecosystem with long-standing company partners that help us fulfill our mission to improve lives.”

Wodicka observes that Purdue is ahead of the curve when it comes to establishing these types of research partnerships – just one of the many ways that the university is a leader among its land-grant brethren.