Purdue student in Indianapolis pushes himself beyond what he thought possible

John Waggle is a Purdue mechanical engineering student in Indianapolis.

Navy veteran John Waggle’s hard work and determination lead to success on Purdue’s new urban campus.

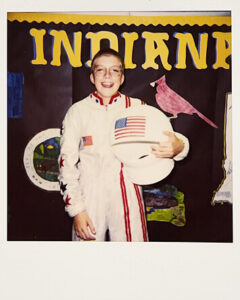

John Waggle’s journey to Purdue University in Indianapolis started with a fateful costume selection in elementary school.

“In fourth grade, we had a dress-up day celebrating famous Indiana residents. I immediately chose Gus Grissom (BSME ’50) because I always wanted to be a Boilermaker, and I always wanted to be an astronaut.”

Waggle still aspires to have a career in space. And he hopes to become the first Purdue student in Indianapolis to join the Cradle of Astronauts.

His persistent pursuit of this goal has taken him to many places — from a Navy nuclear submarine to an astronomical observatory in Hawaii and finally back to Indianapolis.

Plans change

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis was Waggle’s college of choice when he graduated from high school. Growing up on Indy’s east side, he was familiar with both the campus and the school’s well-regarded mechanical engineering technology program.

“It was a solid decision for me at the time,” Waggle says. “But after a few years, I felt a strong pull toward the military. And I knew if I was going to achieve that dream, I needed to pursue it while I was still young.”

Waggle paused his IUPUI education to join the Navy, where he put his academic aptitude and experience into action. He traveled the world for 10 years as a nuclear mechanic, including three years on a submarine and five years on an aircraft carrier.

Experiencing diverse countries and cultures inspired Waggle. “Traveling around so much, meeting so many different people, was both humbling and eye-opening,” he says. “It really expanded my understanding of the world.”

Climb every mountain

As Waggle’s second tour of duty ended, he began thinking through his next steps. A cross country and distance runner in high school, he had always been drawn to activities that pushed his physical limits. And after the high-stress, confined environments of a submarine and an aircraft carrier, Waggle craved wide-open spaces.

He decided to use his GI Bill benefits to enroll in the American Alpine Institute.

“I spent almost an entire year climbing mountains in Washington and taking guide-level training classes. I also did a lot of rock climbing in the Southwest,” Waggle says. “These experiences connected me to the U.S., which I’d been away from for so many years protecting, in a way that was life-changing.”

Rock climbing, backcountry skiing, ice climbing and “dangling off the side of a mountain” were all part of Waggle’s preparation for becoming a mountain guide. But a climbing accident sent him in a new direction.

“I was a part of a rescue of five people injured on Mount Rainier following a rockslide. My friend and I were among the first to arrive at the scene,” he says. “Several of the climbers sustained severe concussions and fractured bones. I was responsible for readying them to be evacuated by helicopter.”

This experience had a profound effect on Waggle.

“Seeing life and death on the mountain, understanding how small we are, how impermanent life is, made me reflect deeply on my future,” he says.

Observatories and observations

Waggle’s next giant leap took him from the mountains of the Pacific Northwest to the summit of Maunakea — a dormant volcano, the highest point in Hawaii and home to the W.M. Keck Observatory.

There he worked as a support supervisor for the team of technicians who change over the twin Keck Observatory telescopes from night to daytime operations. These telescopes, the world’s most scientifically productive optical and infrared telescopes, each weigh 300 tons and operate with nanometer precision.

Waggle and his team were responsible for the maintenance of “pretty much everything” on them. “The instruments, the hardware, the software, electronics, hydraulic systems, we would make any necessary adjustments in preparation for handing them over to the astronomers the next night,” he says.

And then COVID hit.

“It made me realize that I had been away from family for too many years,” he says. “And the decision to return home to Indianapolis felt automatic.”

COVID also prompted Waggle to consider his next career steps.

“There were times when I found myself in professional situations not being taken seriously because I didn’t have a college degree,” he says. “And so I decided to use the GI Bill to return to IUPUI and finish my mechanical engineering technology degree.”

But COVID would again cause Waggle to hit the reset button.

I realized that if I put everything I had into my education, I could push myself further than I ever thought possible.

John Waggle Purdue mechanical engineering student in Indianapolis

Math, math, and more math

Waggle moved back to Indianapolis just as spring COVID closures started to hit. “I had hours and hours of time that I needed to fill,” he says. “So I just started doing math homework.”

Seven hours a day, seven days a week, Waggle worked his way through every math textbook and online problem set he could get his hands on. He went back to the basics and built from there — algebra, geometry, precalculus — all with a goal of enrolling in calculus classes when he returned to IUPUI.

“It was my full-time job,” he says. “While some people were going stir-crazy during COVID, I was learning math.”

His efforts paid off when he enrolled in the summer semester. Waggle hit the ground running with a blistering 18-credit course load, including two math classes.

“I was performing at a level that I didn’t even think myself capable of,” he says. “I got a 100% on a math test, and a light bulb just went off. I realized that if I put everything I had into my education, I could push myself further than I ever thought possible.”

Major change

This realization prompted Waggle to take another giant leap. He switched his major from mechanical engineering technology to mechanical engineering.

“Everybody looked at me funny,” he says. “Most people switch ME majors in the other direction, so I was swimming upstream with this decision. I knew it would be difficult and maybe even uncomfortable at times, but I knew that I could do it.”

Waggle’s academic advisor was less confident.

“My grades at IUPUI before I joined the Navy were far from perfect,” he says. “My counselor was like, ‘Are you sure you want to do this?’”

The answer was a resounding yes.

“I would rather fall short attempting something really difficult,” says Waggle, “than not try at all.”

With this new mindset, Waggle allowed himself to revisit his childhood dream of becoming an astronaut; to set a goal for himself of making that dream a reality.

“I knew that my path to getting where I want to be is to work hard,” he says. “And I knew that success in the classroom could translate into something big outside the classroom.”

And, indeed, it did.

Cummins, Lilly, NASA

Waggle took full advantage of being a college student in Indianapolis, securing two internships at Cummins and one at Eli Lilly and Co.

“Because of my mechanical engineering major, I was able to get these solid internships and be taken seriously by organizations that normally may have filtered me out,” he says.

For his first internship project at Cummins, Waggle created a detailed fuel systems product validation manual for potential use in the company’s overseas production plants.

His second Cummins internship dealt with EPA compliance. “I worked on engines, looking at emissions testing and making sure that all of the after-treatment systems were working correctly,” he says.

At Lilly, Waggle worked on the team responsible for utilities and design engineering at the company’s new Lebanon, Indiana, site.

Waggle learned of the highly competitive NASA Pathways program at a lecture he attended on the space agency’s all-electric experimental Maxwell aircraft. The presenters encouraged him to apply, and he went for it. “I didn’t hear back from them for weeks,” he says. “So I just assumed that I didn’t get it.”

I would rather fall short attempting something really difficult than not try at all.

John Waggle

Purdue mechanical engineering student in Indianapolis

Until one day an email with a government address landed in his inbox.

“It looked like a generic rejection letter,” Waggle says. “Every section started out with: ‘You have not been selected.’ But then I scrolled down to the Johnson Space Center and Kennedy Space Center sections, and I realized that my application had been forwarded to those agencies.”

His response was instantaneous. “I pretty much lost my mind,” he says.

Waggle ultimately ended up at Johnson Space Center where he worked in the Flight Operations Directorate on the Automated Stowage Drawings project.

“John made such an impact during his Pathways tour,” says Lauren Bakalyar, a 2005 Purdue graduate (BSIE) and chief of NASA’s Mission Operations Planning and Integration Branch. “His work improved the Flight Control Team’s understanding of the stowage space available onboard the International Space Station and helps us guide the astronauts to the best methods to stow important hardware and experiments.”

Waggle’s first internship with NASA ended in December, but he will be going back in May to complete a summer internship. He has a third lined up for the fall.

Student group and solar eclipse

Back on campus in Indianapolis, Waggle and other members of the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS) club engineer and launch weather balloons that measure payload as well as radiation at high altitudes.

“We successfully sent balloons up to 100,000 feet with cameras on board,” he says. “And we are analyzing the data, video and pictures we got back.

“I started looking at the solar eclipse as a huge objective we could hit. We are aiming to launch three balloons to see what kind of radiation data we get back and how it compares to previous experiments.

“We also really want pictures of the solar eclipse at altitude.”

As a leader of the SEDS group, it’s important to Waggle to provide invaluable experiences for other students and to offer mentorship when it comes to communication skills.

“I tell them, ‘Future employers are not going to want you to present differential equations to them,’” he says. “They want you to be able to explain your research in a way that makes sense and is appropriate for the audience.

“Being able to produce good work and being able to communicate that work back and forth is the most effective thing you can do as an engineer.”

What next?

Waggle will transition from IUPUI to Purdue University in Indianapolis when the school officially launches July 1. He is excited about the new opportunities this will create, especially for collaboration between Purdue’s two campuses.

“I look forward to making connections with the West Lafayette campus and its students,” he says. “My life is centered in Indianapolis, and it makes sense for me to live and learn here. But I am excited to have back-and-forth exchanges and increased involvement between the two campuses.”

And that childhood dream of space? “I drove up to West Lafayette last weekend and bought a Cradle of Astronauts shirt.”