Family, college and opportunity: Samantha’s Purdue Global comeback

This mom is excited to see where her bachelor’s degree in business administration will take her

In her final term at Purdue Global, Samantha Tatman looks back on the past few years and says it’s an era she never saw coming. But knowing she’s created opportunities for her family has been everything to her.

Tatman went to community college after high school, but since she and her husband were starting a family, it was clear early on that she’d have to make some sacrifices. She decided she needed to take a break from higher education. “My husband was in an apprenticeship, and we just couldn’t do both at the same time,” she says.

As a young parent, she knew it was best for her family that she went straight into the workforce while her husband finished his apprenticeship. She thought that was the end of her educational journey.

But she was wrong.

The journey back to school

As a working mom with two kids, dogs and endless activities, the prospect of going back to school 12 years after leaving community college felt overwhelming. It was her husband who convinced her that it was her time.

He’d completed his lineman apprenticeship, around 7,000 hours of an intensive, hands-on education that taught him to build and maintain electrical power systems. When he got his qualifications after years of hard work, he knew she could make her own comeback.

“He said, ‘It’s your turn. You need to have this good feeling too.’ He’s my biggest cheerleader. One hundred percent.”

Tatman already had a job in health care, so at first she struggled to see the merit in earning a degree. But she gradually began to see things differently.

She realized a degree in business administration could open doors for her. She had worked in multiple health care positions, but she liked the thought of having a steppingstone to other opportunities. She wouldn’t be limited to direct care. She could move up to administration. And if she wanted to leave health care entirely, it would still be possible to advance.

Without a degree, her past experience wouldn’t be enough to make a move like that possible. So, with a major in mind, she only had one more thing to figure out: finding the right school.

Choosing the right path

Tatman had several institutions on her list when she first started looking. But Purdue Global quickly rose to the top because she immediately had a sense that the admissions counselors cared. They went the extra mile in connecting with her and making her feel welcome.

“They want what’s best for you,” Tatman says. “I feel like everybody I’ve talked to at Purdue Global cares about me. That’s what made me choose Purdue Global.”

Her advisor made a difference from the start, making sure all of Tatman’s questions were answered and that she filled out the correct paperwork.

When it was time to begin mapping out her classes, she thought she would pursue the standard path to an associate degree. But her advisor believed she was capable of more and told her the ExcelTrack bachelor’s degree program would take her further. Since she already had credits from her community college, a bachelor’s degree was more attainable than she thought.

With ExcelTrack, students combine their college credit and professional experience with an accelerated course schedule and customize their program to earn a degree faster. But could she really earn a bachelor’s degree on an accelerated program?

With her husband, family and Purdue Global advisors supporting her, Tatman only needed to convince one more person — herself.

The more she looked at the facts, her hesitance completely changed. “After I got going with it,” she says, “I’m so glad. I’m so glad that I pushed myself.”

She loves how, even on an accelerated track, her degree program doesn’t overwhelm her or take time away from her family. With her kids’ sports, piano lessons and cheerleading, she wondered how she would balance everything, but she has been pleased by how she’s been able to manage all her commitments.

“I have this self-discipline, and that really helps with my schooling. I can do homework anytime, anywhere. I love that flexibility,” she says. “Ninety-nine percent of the time, I do my homework in between commitments, or I do it at night while everyone’s in bed.”

Even when life doesn’t go as planned, Tatman is thankful for the people around her. “I’m the one doing the work and getting this done, but it does take a support system. There are times when I’ll call my mom and ask her to take the kids for a few hours. My kids are even very understanding. They know, OK, it’s homework time, and I can work on my assignments.”

An unexpected benefit to pursuing her degree has been the opportunity to teach an important lesson to the people she loves most.

“The biggest thing is showing my kids, if you put your mind to something, you can do literally anything that you want,” she says.

Graduation and beyond

With her degree nearing completion, Tatman reflects on how her experience has been important to her own personal journey, not just her family’s. When asked about her upcoming graduation, her smile grows bigger and brighter.

“I know I’ll be very proud. I’ll honestly probably cry,” she says. “I already feel proud of myself, just by going back and making the commitment to do this. Being 30 years old, I feel like it’s my time to do something for myself.”

Ultimately, she is happy she followed her husband’s advice and proved herself wrong. “Some people might think it’s silly to go back to school when you are an adult with a family, but if you want that for yourself, or if you want it for your family to see you have a drive for something, I think you should absolutely do it. It will be very rewarding,” she says.

She is more than excited to see where her business administration degree from Purdue Global will take her. “It can lead me anywhere,” she says. “I just have to decide.”

I’m so glad that I pushed myself.

Samantha Tatman BS business administration, Purdue Global

Motorsports engineering student driven by passion for racing

Reed England is accelerating his Purdue career through one-of-a-kind experiences in Indianapolis

In the racing world, they say who you know is everything. Because of his experiences as a Purdue motorsports engineering student in Indianapolis, Reed England knows a lot of people.

As vice president and crew chief of the motorsports club, he’s met engineers, drivers, crew chiefs and racing staff members.

“I’ve also learned a lot about internships from other students and from recent graduates who already have jobs in the field,” he says.

England continues to rack up opportunities through networking. “The summer between my first and second year, I volunteered at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and secured a spot traveling with a racing series,” he says.

Through another motorsports club connection, England worked as a systems engineer for Bryan Herta Autosport on the team’s No. 98 Hyundai Elantra N TCR car running in the IMSA Michelin Pilot Challenge.

Currently, he is a data acquisitions engineer for the three JTR Motorsports Engineering Porsche 911 992 GT3 Cup cars running in the Porsche Sprint Challenge North America, as well as for two Ligier JS P3 LMP3 cars running in the IMSA VP Racing Sportscar Challenge.

And it’s not just England who is making connections.

“Last year we had a motorsports engineering student or alum on 32 of the 33 IndyCars at the Indianapolis 500,” he says.

Last year we had a motorsports engineering student or alum on 32 of the 33 IndyCars at the Indianapolis 500.

Reed England Purdue motorsports engineering student in Indianapolis

One of a kind

Purdue University in Indianapolis has the only ABET-accredited undergraduate motorsports engineering program in the U.S. It is truly one of a kind. It’s also the reason England chose Purdue.

“I fell in love with cars and racing early on,” he says. “I knew it was the career path for me, but I always thought I would approach it through a degree in mechanical engineering.”

A story on his local early morning news channel set the Columbus, Indiana, resident in a new direction.

“My junior year of high school, I just happened to see a news feature on the motorsports engineering program, and I was like, ‘That’s it. That’s the degree I need to pursue.’”

The ‘Racing Capital of the World’

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway (IMS), home of iconic races like the Indianapolis 500 and the Brickyard 400, is only 3 miles from the Purdue campus in Indianapolis — an obvious advantage for motorsports students like England.

“When a racing season ends, teams are deciding whether they want to add a new car to their roster or begin a new project requiring more engineers,” he says. “Because of our location and reputation, Purdue in Indianapolis is one of the first places teams look to fill open roles.”

England says these types of employment and internship opportunities were the biggest draws to the university for him. “Within 20 minutes any direction of campus are numerous racing teams and engineering companies,” he says.

Hands-on learning

Proximity to the IMS also brings with it plenty of hands-on learning experiences.

“Being able to go into the paddock and see the industry at work in person has been incredibly motivating,” he says. “It’s exciting, and it just continues to solidify for me that motorsports engineering is what I really want to do after I graduate.”

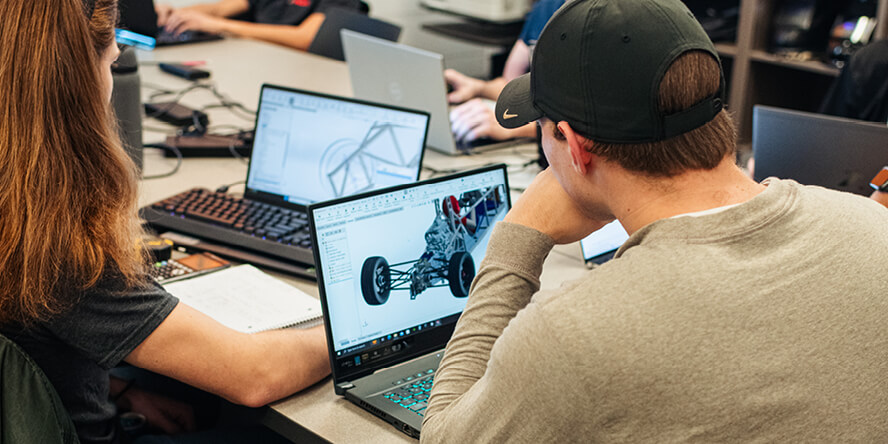

England’s immersive experiences on the track have been mirrored in the classroom.

“My data acquisition classes have taught me software systems like Pi Toolbox and WinTAX4, which I need to analyze data and work as a data acquisitions engineer,” he says.

“I was able to step in and work at a more advanced level with the software than anyone else on my current racing team,” he adds.

The opportunity to lead engineering projects on actual race cars is a huge benefit, England says.

“On Fridays I spend most of my time collaborating with my class project partners at the Stutz building downtown,” he says. “It’s where we keep all our race cars, engineering materials, 3D printers. It’s also where we design and build.”

Close community

Indianapolis has a lot to offer college students outside of racing, too. And England said he takes advantage of it all. “You can walk pretty much everywhere,” he says.

“We don’t have a traditional campus,” he says. “Instead, we have downtown Indy. There are so many great restaurants, concerts and sporting events. When we’re not at the speedway, my friends and I like to watch the Indy Fuel play hockey. We also catch shows at the Everwise Amphitheater.”

For England, an unexpected bonus of learning in the city is that he has formed so many close connections on campus, and it all started during new student orientation.

“I was able to meet so many other people,” he says. “And the cool thing is that they were from different majors, different cities, even different countries. We did all these activities together. It was a great introduction to campus and a fun way to meet new people.”

Residence hall life and student clubs were another way that England made new friends on campus.

“The dorms were such an easy way of meeting people, especially my first year,” he says. “That’s where I made a lot of my friends, and now we all live in the same off-campus apartment building.”

England has an academic scholarship that connects him to students outside of his major, especially when they are doing volunteer work together on campus at Paws’ Pantry, which offers free healthy food to students and employees struggling with food insecurity.

Next steps

England, a junior, is looking ahead to graduation and getting into the field full time.

In the meantime, he is excited to cross the finish line with several engineering projects, including a rebuilt MGB GT, a Mazda Miata with updated radiator and fuel intake systems, and a former Formula SAE car that he and his team have been revamping.

“The more cars we have to drive and race in our motocross rotation, the more experience and knowledge we can gain for the future,” he says. “And there’s nothing more satisfying than creating something and then using it for competition.”

Purdue student in Indianapolis pushes himself beyond what he thought possible

Navy veteran John Waggle’s hard work and determination lead to success on Purdue’s new urban campus.

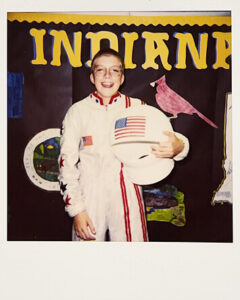

John Waggle’s journey to Purdue University in Indianapolis started with a fateful costume selection in elementary school.

“In fourth grade, we had a dress-up day celebrating famous Indiana residents. I immediately chose Gus Grissom (BSME ’50) because I always wanted to be a Boilermaker, and I always wanted to be an astronaut.”

Waggle still aspires to have a career in space. And he hopes to become the first Purdue student in Indianapolis to join the Cradle of Astronauts.

His persistent pursuit of this goal has taken him to many places — from a Navy nuclear submarine to an astronomical observatory in Hawaii and finally back to Indianapolis.

Plans change

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis was Waggle’s college of choice when he graduated from high school. Growing up on Indy’s east side, he was familiar with both the campus and the school’s well-regarded mechanical engineering technology program.

“It was a solid decision for me at the time,” Waggle says. “But after a few years, I felt a strong pull toward the military. And I knew if I was going to achieve that dream, I needed to pursue it while I was still young.”

Waggle paused his IUPUI education to join the Navy, where he put his academic aptitude and experience into action. He traveled the world for 10 years as a nuclear mechanic, including three years on a submarine and five years on an aircraft carrier.

Experiencing diverse countries and cultures inspired Waggle. “Traveling around so much, meeting so many different people, was both humbling and eye-opening,” he says. “It really expanded my understanding of the world.”

Climb every mountain

As Waggle’s second tour of duty ended, he began thinking through his next steps. A cross country and distance runner in high school, he had always been drawn to activities that pushed his physical limits. And after the high-stress, confined environments of a submarine and an aircraft carrier, Waggle craved wide-open spaces.

He decided to use his GI Bill benefits to enroll in the American Alpine Institute.

“I spent almost an entire year climbing mountains in Washington and taking guide-level training classes. I also did a lot of rock climbing in the Southwest,” Waggle says. “These experiences connected me to the U.S., which I’d been away from for so many years protecting, in a way that was life-changing.”

Rock climbing, backcountry skiing, ice climbing and “dangling off the side of a mountain” were all part of Waggle’s preparation for becoming a mountain guide. But a climbing accident sent him in a new direction.

“I was a part of a rescue of five people injured on Mount Rainier following a rockslide. My friend and I were among the first to arrive at the scene,” he says. “Several of the climbers sustained severe concussions and fractured bones. I was responsible for readying them to be evacuated by helicopter.”

This experience had a profound effect on Waggle.

“Seeing life and death on the mountain, understanding how small we are, how impermanent life is, made me reflect deeply on my future,” he says.

Observatories and observations

Waggle’s next giant leap took him from the mountains of the Pacific Northwest to the summit of Maunakea — a dormant volcano, the highest point in Hawaii and home to the W.M. Keck Observatory.

There he worked as a support supervisor for the team of technicians who change over the twin Keck Observatory telescopes from night to daytime operations. These telescopes, the world’s most scientifically productive optical and infrared telescopes, each weigh 300 tons and operate with nanometer precision.

Waggle and his team were responsible for the maintenance of “pretty much everything” on them. “The instruments, the hardware, the software, electronics, hydraulic systems, we would make any necessary adjustments in preparation for handing them over to the astronomers the next night,” he says.

And then COVID hit.

“It made me realize that I had been away from family for too many years,” he says. “And the decision to return home to Indianapolis felt automatic.”

COVID also prompted Waggle to consider his next career steps.

“There were times when I found myself in professional situations not being taken seriously because I didn’t have a college degree,” he says. “And so I decided to use the GI Bill to return to IUPUI and finish my mechanical engineering technology degree.”

But COVID would again cause Waggle to hit the reset button.

I realized that if I put everything I had into my education, I could push myself further than I ever thought possible.

John Waggle Purdue mechanical engineering student in Indianapolis

Math, math, and more math

Waggle moved back to Indianapolis just as spring COVID closures started to hit. “I had hours and hours of time that I needed to fill,” he says. “So I just started doing math homework.”

Seven hours a day, seven days a week, Waggle worked his way through every math textbook and online problem set he could get his hands on. He went back to the basics and built from there — algebra, geometry, precalculus — all with a goal of enrolling in calculus classes when he returned to IUPUI.

“It was my full-time job,” he says. “While some people were going stir-crazy during COVID, I was learning math.”

His efforts paid off when he enrolled in the summer semester. Waggle hit the ground running with a blistering 18-credit course load, including two math classes.

“I was performing at a level that I didn’t even think myself capable of,” he says. “I got a 100% on a math test, and a light bulb just went off. I realized that if I put everything I had into my education, I could push myself further than I ever thought possible.”

Major change

This realization prompted Waggle to take another giant leap. He switched his major from mechanical engineering technology to mechanical engineering.

“Everybody looked at me funny,” he says. “Most people switch ME majors in the other direction, so I was swimming upstream with this decision. I knew it would be difficult and maybe even uncomfortable at times, but I knew that I could do it.”

Waggle’s academic advisor was less confident.

“My grades at IUPUI before I joined the Navy were far from perfect,” he says. “My counselor was like, ‘Are you sure you want to do this?’”

The answer was a resounding yes.

“I would rather fall short attempting something really difficult,” says Waggle, “than not try at all.”

With this new mindset, Waggle allowed himself to revisit his childhood dream of becoming an astronaut; to set a goal for himself of making that dream a reality.

“I knew that my path to getting where I want to be is to work hard,” he says. “And I knew that success in the classroom could translate into something big outside the classroom.”

And, indeed, it did.

Cummins, Lilly, NASA

Waggle took full advantage of being a college student in Indianapolis, securing two internships at Cummins and one at Eli Lilly and Co.

“Because of my mechanical engineering major, I was able to get these solid internships and be taken seriously by organizations that normally may have filtered me out,” he says.

For his first internship project at Cummins, Waggle created a detailed fuel systems product validation manual for potential use in the company’s overseas production plants.

His second Cummins internship dealt with EPA compliance. “I worked on engines, looking at emissions testing and making sure that all of the after-treatment systems were working correctly,” he says.

At Lilly, Waggle worked on the team responsible for utilities and design engineering at the company’s new Lebanon, Indiana, site.

Waggle learned of the highly competitive NASA Pathways program at a lecture he attended on the space agency’s all-electric experimental Maxwell aircraft. The presenters encouraged him to apply, and he went for it. “I didn’t hear back from them for weeks,” he says. “So I just assumed that I didn’t get it.”

I would rather fall short attempting something really difficult than not try at all.

John Waggle

Purdue mechanical engineering student in Indianapolis

Until one day an email with a government address landed in his inbox.

“It looked like a generic rejection letter,” Waggle says. “Every section started out with: ‘You have not been selected.’ But then I scrolled down to the Johnson Space Center and Kennedy Space Center sections, and I realized that my application had been forwarded to those agencies.”

His response was instantaneous. “I pretty much lost my mind,” he says.

Waggle ultimately ended up at Johnson Space Center where he worked in the Flight Operations Directorate on the Automated Stowage Drawings project.

“John made such an impact during his Pathways tour,” says Lauren Bakalyar, a 2005 Purdue graduate (BSIE) and chief of NASA’s Mission Operations Planning and Integration Branch. “His work improved the Flight Control Team’s understanding of the stowage space available onboard the International Space Station and helps us guide the astronauts to the best methods to stow important hardware and experiments.”

Waggle’s first internship with NASA ended in December, but he will be going back in May to complete a summer internship. He has a third lined up for the fall.

Student group and solar eclipse

Back on campus in Indianapolis, Waggle and other members of the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS) club engineer and launch weather balloons that measure payload as well as radiation at high altitudes.

“We successfully sent balloons up to 100,000 feet with cameras on board,” he says. “And we are analyzing the data, video and pictures we got back.

“I started looking at the solar eclipse as a huge objective we could hit. We are aiming to launch three balloons to see what kind of radiation data we get back and how it compares to previous experiments.

“We also really want pictures of the solar eclipse at altitude.”

As a leader of the SEDS group, it’s important to Waggle to provide invaluable experiences for other students and to offer mentorship when it comes to communication skills.

“I tell them, ‘Future employers are not going to want you to present differential equations to them,’” he says. “They want you to be able to explain your research in a way that makes sense and is appropriate for the audience.

“Being able to produce good work and being able to communicate that work back and forth is the most effective thing you can do as an engineer.”

What next?

Waggle will transition from IUPUI to Purdue University in Indianapolis when the school officially launches July 1. He is excited about the new opportunities this will create, especially for collaboration between Purdue’s two campuses.

“I look forward to making connections with the West Lafayette campus and its students,” he says. “My life is centered in Indianapolis, and it makes sense for me to live and learn here. But I am excited to have back-and-forth exchanges and increased involvement between the two campuses.”

And that childhood dream of space? “I drove up to West Lafayette last weekend and bought a Cradle of Astronauts shirt.”

‘I’ve always wanted to be a writer’

Abby Steiner’s bachelor’s in communication from Purdue Global is opening doors to new opportunities for herself and her family

“I’ve always wanted to be a writer. Always wanted to. I’ve dreamed of it.”

To Abby Steiner (BS communication, Purdue Global), becoming a professional writer seemed unattainable. It was a career goal she had always thought about but never believed she’d have the chance to achieve.

While she’d had good jobs over the years, Steiner finally decided she was done settling for work that didn’t excite her.

“I got to the point where it was like, why settle for good when you could find amazing?” she says.

That’s when she decided to go for her dream job. It all started with Purdue Global.

Now in the final year of her bachelor’s in communication, Steiner reflects on how her academic success gave her the confidence to apply for a copywriting position at Find8 Performance Marketing. Steiner believes that working full time while pursuing her degree distinguished her from other applicants by showing how serious she was about her career. And it helped her land the job.

“Having Purdue Global on my resume shows a real commitment and a real dedication,” she says. “I think someone with the same qualifications as me who didn’t have that on their resume probably wouldn’t have gotten chosen. The Purdue Global name stands out to people. It just does.”

So what led Steiner to Purdue Global? Like so many who are looking for new opportunities, it was her love for family.

Full-time student. Full-time mom.

When COVID-19 hit, economic realities became more apparent to Steiner. She wanted to be sure her husband and their young daughter, Avery, would never have to worry, but there was a dark cloud hanging above her head: She didn’t have a degree to fall back on.

“You’re considering other people and their future when you’re making these decisions,” she says.

Her family was a big part of her decision to go back to school, but she wondered if she would have to sacrifice her personal life to earn her degree. Thankfully, the answer was no. The flexibility and support Purdue Global offers allowed Abby to work her dream job while keeping up with her daughter’s many activities. She appreciates how classes are set up and that the faculty are there to help her. Dance team, gymnastics, theater, and voice lessons keep 7-year-old Avery busy, and Abby doesn’t have to miss a moment.

“Everyone is super supportive because most of us at Purdue Global are working adults,” she says. “Most of the people I’ve encountered are parents or do have a family.”

Parents interested in pursuing a higher education degree shouldn’t worry that it will take time away from what matters most, Abby says, because at Purdue Global, balance is possible.

“Give yourself that opportunity to do this for yourself,” she says to parents like her. “Your kids are going to respect you for it. They’re going to see you working hard. It’s going to build your confidence. And you’re going to find support once you get there.”

The Purdue Global name stands out to people. It just does.

Abby Steiner BS communication, Purdue Global

An unexpected boost of confidence

Abby says her experience as an adult student helped her better understand why college didn’t work out the first time around.

When Abby enrolled at a traditional public university right out of high school, she felt out of place. The transition from living in a small town to suddenly attending a Big Ten school was overwhelming. So when she decided to try to get her degree as a working adult, she worried that the same feeling would come again. But it didn’t.

All she needed was a more supportive environment and a sense of belonging, and she found it at Purdue Global.

“You meet people from the same walk of life as you,” she says. “People going through the same things or also trying to balance work and family, so there’s a lot of people you can relate to. It wasn’t this big overwhelming monster of a lecture hall with a bunch of people I didn’t know. This was way better.”

Abby is not just fitting in at Purdue Global — she’s also soaring academically. “I got a great grade in my first class, and I realized I’m totally capable of this,” she says.

Receiving those good grades boosted her confidence and made her understand that even if her family was her main motivation for getting a degree, it was also an important accomplishment for herself.

“I think it’s easy to lose ourselves in doing things for others — our kids, our family,” she says. “This started out as something I felt I should do for them, but then it became something I was doing for me. It really makes a difference in how I feel about myself.”

Realizing she was more than capable of earning a degree gave Abby the confidence to apply for that dream position as a writer. She saw herself in a new light. If she could be successful at Purdue Global, what was stopping her from being a successful writer?

Today, Abby continues living out her dream as a copywriter. She says, “I love it here. It’s a dream job. Someone is paying me a salary to write.”

So what’s next for her? She is hoping to move up in her company — a promotion that is only possible with a degree.

Not getting a degree was a big regret for Abby, but not anymore. She knows that her 19-year-old self, who felt lost in her first college lecture, would be proud to see the Abby of today with a 3.6 GPA, her dream copywriter job and soon, the degree to propel her career even further.

Purdue women’s space program establishes a confident community

Students form ties to peers, industry leaders and astronauts in the only college organization of its kind

It’s a career path so extraordinary that finding a starting point can seem impossible.

Most dream jobs have maps: earn this degree, get that internship, meet those professionals. When a certain sequence is followed, it results in landing a role.

But what if someone’s shooting for the stars?

“This is what I want to do for the rest of my life,” says Roha Gul, a graduate student in autonomy and control with a focus in astrodynamics and space applications. “I want to be a part of space exploration.”

Gul is achieving her dream after joining Purdue’s Leading Women Toward Space Careers program. Founded in 2022 in the John Martinson Honors College in partnership with the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation, the program connects Boilermakers to astronauts and researchers at the forefront of innovation, including specialists from NASA and commercial spaceflight companies.

Leading Women Toward Space Careers is the only college program of its kind. Through mentorship meetings, workshops and space center visits, students learn how to progress in their career paths. They’re also gaining the greatest resource: a community that listens to them, uplifts them and lets them know they’re never alone.

There is a level of devotion that you can’t find anywhere else other than Purdue.

Madelyn Whitaker

BS biological engineering ’24

Finding a network

Twenty-seven Purdue alumni have gone into orbit, designating the university as the Cradle of Astronauts. But Purdue has produced more than commanders, pilots and mission specialists. It also has educated talent across the space industry, including researchers, data scientists and engineers who improve everything from software to spacesuit design.

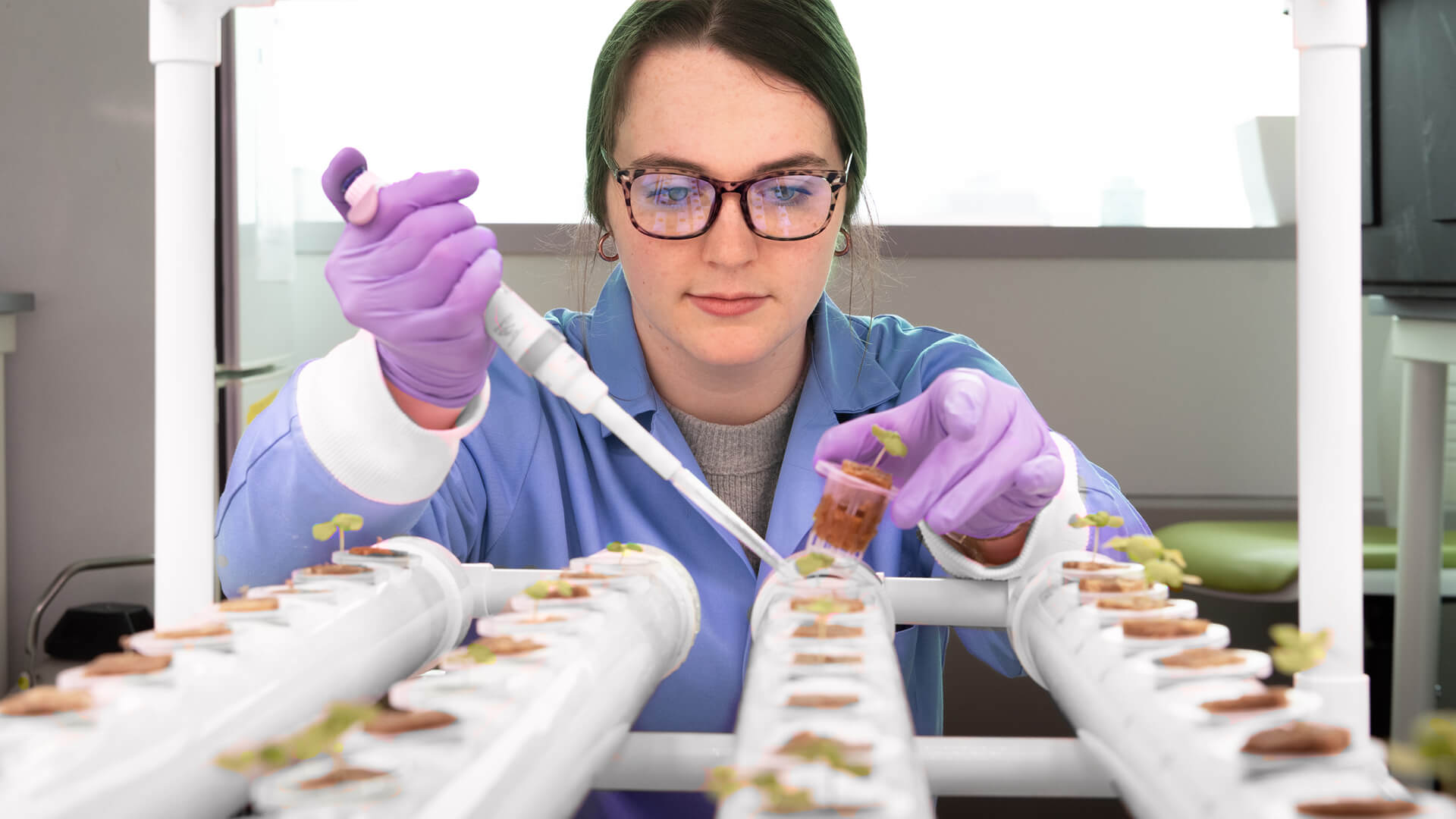

“There is a level of devotion that you can’t find anywhere else other than Purdue,” says Madelyn Whitaker, a senior majoring in biological engineering with minors in biotechnology and data driven agriculture. “People are dedicated and want to give back. They’re proud to be a Boilermaker and see students who work to make our network even better.”

Whitaker’s mentors are both affiliated with NASA. From them, she’s learned more about what it takes to get hired — and how to navigate new environments. She’s grateful that mentors have given the students solid advice on how to recognize where they’ll thrive and what to do in a field that’s not predominantly female.

“It can be difficult when you don’t feel like you’re represented in the workplace,” Whitaker says. “We’ve had a lot of conversations about how to effectively communicate your needs and advocate for other women. Mentors found ways to do that in their careers, and it’s going to support the steps we take.”

In the future, Whitaker will contribute to astrobotany and space biology. She strives to develop sustainable biological solutions for our planet and beyond. Already, she’s been able to dive into impressive research, like conducting fieldwork as an analog astronaut at the Mars Desert Research Station as well as growing soybeans in lunar and Martian simulations.

Leading Women Toward Space Careers has instilled a sense of true belonging in what comes next after earning an undergraduate degree, replacing Whitaker’s previous anxiety about breaking into the space industry.

“It’s been life-changing to be in proximity to these amazing women, because, at the end of the day, you realize that they are humans,” she says. “Through mentorship circles, I’ve realized that everyone’s just a person. They’re approachable; they have a favorite food; they have hobbies. It makes it so much easier to connect. They’re more than their work, and it’s been important for me to realize that.”

Strengthening skills

Mentorship circles have united mentors and mentees, creating relationships that emphasize feeling seen and heard — and with that, paying attention and listening. The conversations create personal and professional benefits.

“One of the biggest things my circle has given me is a safe space,” Gul says. “My mentors have become friends. I feel truly accepted for who I am and what I want, which is very empowering.”

Every Leading Women Toward Space Careers member brings different experiences to the table. Students come from all over the world. Most have different aspirations and areas of interest. Yet, through it all, there’s a common thread. Gul enjoys getting to know younger mentees and being able to relate to so many of their stories.

“As a grad student, hearing the other women’s stories and what their points of view are is inspiring,” she says. “Even though they’re younger, I’m always learning something from them.”

Before she came to Purdue for her master’s degree, Gul studied aerospace engineering in Pakistan. She’s interested in using optimal control methods for guidance for space vehicles. Right now, she’s researching how artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques can help with guidance, control and navigation.

Friendships in the program have helped her acclimate to the U.S. and strategize her postgraduation plans. She felt welcomed with open arms when she joined, and now she can say that she’ll always have people who have her back in the next stage.

“It’s been amazing,” she says. “You build solidarity as you go through the same things. When you talk to people here, you find that sense of comfort. No matter where I go, I’ll have that.”

People in the program are so interesting and always pushing the envelope of what’s possible.

Arianna Cobb Morgan State University student

Preparing for the future

Distance doesn’t stall the program’s purpose. Wherever life leads, the ties hold strong. Those connections aren’t limited to Indiana. In 2023, Leading Women Toward Space Careers expanded to Morgan State University, a historically Black university in Baltimore. Purdue has collaborated with Morgan State on a number of strategic initiatives, including a 3+2 dual-degree partnership.

“When I met everyone, we instantly clicked,” says Arianna Cobb, a Morgan State sophomore studying industrial engineering. “I want to be lifelong friends with these women. Even though we’re not on the same campus, I always feel included.”

Every month, mentorship circles meet virtually for conversations about current projects, networking opportunities and anything else that comes to mind. Members also communicate in a group chat. Throughout the year, they meet for events and workshops, bonding on trips to conferences and NASA centers.

Cobb credits the program as a priceless source of information one wouldn’t hear otherwise. “People in the program are so interesting and always pushing the envelope of what’s possible,” she says. “Everyone’s contributing to some amazing research, getting outstanding internships, meeting different people.”

Finding out about others’ work has been encouraging for Cobb, whose passion for astrophysics traces back to a very young age. Her grandfather was a physics teacher, and her father passed on the love for science. “My dad used to put on ‘Through the Wormhole,’ Morgan Freeman’s science show, and I was obsessed,” she says with a laugh. “I wanted to understand coding languages and would show up to fifth grade class with packets of binary code I wrote.”

Now she’s studying to advance space exploration alongside other women who have their own stories of interest-sparking shows, memorable science classes and fascinations with the solar system.

Together, they’re changing the future of the industry.

“Every mentor, every meeting, every interaction solidifies my passion for this,” Cobb says. “The program has completely connected us, even if we’re miles apart.”

Meet Purdue Global professor Bea Bourne: ‘I was an adult student, too!’

This MBA professor earned all three of her degrees as a mom and working adult, and now she’s here to help others.

As a professor for the MBA program and senior lead for diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging within Purdue Global’s School of Business, Bea Bourne shares the why behind her work.

I started at AT&T right out of high school and moved up through the ranks. The job I enjoyed most was as a corporate trainer for sales. It’s where I discovered what I’m intended to do: teach. There’s nothing like experiencing a learner’s lightbulb moment and seeing someone connect to a concept. It led me to Purdue Global, where I teach in the MBA program and serve as the senior lead of diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging for the School of Business and Information Technology.

I wanted to work with adults from the start. I completed all my degrees — my bachelor’s, my master’s and my doctorate — as a working adult. I know the work; I know what it’s like to balance being a student, parent and working professional.

I am doing what I was created to do because of that journey. I see myself in my students, and I believe this is where I can make a difference, by helping other working adults advance toward what they are created to do as well.

I am fortunate to work with a group of fellow faculty and staff members who want to be here as much as I do. We are involved and care about the success of our students. That passion for student success carries over to the other part of my work, too. As senior lead for diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging in the School of Business, I enjoy working with others to create initiatives within our school that foster better engagement, a sense of belonging and more inclusion. In this space, the challenges we address are present everywhere. They are universal.

I try to celebrate the wins and concentrate on what I can change. We’ve had real successes throughout all the schools. For example, an inaugural chief diversity officer was appointed. We created a curriculum guide for our professors on diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging principles. Juneteenth is now a university holiday, and we have a university diversity statement. There have been other wins, and I hang my hat on the fact that I can see the needle being moved.

That’s what keeps me going. Meaningful change isn’t instant, like flipping a switch. It’s slow and steady.

I see myself in my students, and I believe this is where I can make a difference.

Bea Bourne Professor, Purdue Global

Purdue Global student says ‘this comeback is for all of us’

Business administration major Alejandra Palma’s dream honors her family

Alejandra Palma (BS business administration, Purdue Global) says the part of her childhood in Chile that serves as her ultimate North Star is the evening walks she used to take with the love of her life — her dad. Every night, they used to catch the views of the city and talk.

“The first years of my life, it was just me and my father,” she says. “He had to work a lot, so at night after dinner, he took my hand and we walked to a viewpoint where we could see the city. It was our ritual before going to sleep.”

In true childlike fashion, she would tell him how much she loved him. How she would always love him, just like this. He would tell her, no, she was going to grow up and make a life for herself, and that’s a good thing; they would both be at peace with it. She would say, nope. She was going to bring him along to live with her. “But I’ll be a grumpy old man!” he would say. But Palma thought he could get old and grumpy all he wants, but no matter where her adventures took her, she vowed to be right there with him and love him just the same.

Those adventures would take her overseas. But that’s where things took an unexpected turn. Rather than fulfilling her dream of opening a permanent-makeup studio in the United States, she found herself facing her own mortality. She says her brush with death gave her a new outlook on herself and the world around her, and it led her to Purdue Global.

That’s where her comeback began. What she didn’t know was how profoundly her family would feel ownership of it, too.

A passion for beauty

“I’ve always heard that if you don’t work for your own dreams, somebody else will hire you to work for their dreams,” Palma says. That’s why she always knew she wanted to carve her own path as an entrepreneur. And she knew exactly what she wanted to do, too.

Years after her nightly walks with her dad, she had sisters to play with. More to the point, she had sisters with hair — prime for a fresh cut. At 10 years old, Palma accepted the challenge.

A lot of people may have had a sibling cut their hair, but the haircut Palma gave her sister was dramatic. Her sister’s hair started out very long and ended up in a chin-length bob. It got a surprising reaction from the grownups.

“I wasn’t grounded or anything because I made a perfect cut!” she says.

It was then that she knew. Drawing out the beauty in others was her greatest passion.

As she grew up, she identified what it was about fashion and cosmetology that brought her joy. “Every woman is beautiful,” she explains. “But if I can help somebody to feel more beautiful or show somebody something they don’t know they have, that’s what means a lot to me.”

She took the first step as a young adult by going to beauty school in Chile and becoming a licensed cosmetologist. Then, along with a friend, she opened up a small studio. But she still wanted more. She felt like she had the “what” right but not the “where.” Her ultimate dream was doing the same thing in the United States, so she sold her portion of the studio to her business partner and she moved to the States to pursue her highest dream.

That move saved her life.

The will to fight

Her first step after moving to the States was to get the income flowing, so she took a manual labor job in a factory while she worked on plans to open the studio. Three months into the new job, her insurance benefits kicked in, and she immediately made an appointment for a checkup with a primary care physician.

It was supposed to be routine — she felt completely normal — but it turned into the moment everyone fears. The anomaly. The additional tests. The call.

Cancer.

While it’s never a good moment for a cancer diagnosis, the timing couldn’t have been worse. Palma was in a new country, didn’t speak the language, had no network of loved ones nearby. Although she knew she was brave, ready to take on any challenge, this one wiped out her strong will.

“It changed everything,” she says. “I went from being a completely healthy person to an oncology patient with no desire to fight.”

Now, so suddenly, she was 37 years old and considering end-of-life decisions. She says she didn’t want to spend her final days anywhere but with her two sons, so Palma went to her supervisor with the intent to quit her job. Her boss wouldn’t have it. She believed Palma could get through this and encouraged her to take a medical leave so she could get paid, keep her insurance and have something to work toward that had nothing to do with cancer.

It not only gave her the resources she needed to fight cancer, it gave her the will to fight it. And she did.

“Without a doubt, it was one of the most difficult periods of my life,” she says. “It was full of uncertainties, pain and emotional turmoil, but it also led me to profound personal growth. Now, I feel more appreciation for life. It made me resilient. I am more empathetic. I learned to evaluate my priorities. I saw the fragility and beauty of life, and I saw the spirit of the human being and the connections that can be born.”

Armed with a fresh will to fight, Palma endured treatments, one after another, and finally received good news. She was in remission.

But by then, something inside had shifted. She was still dreaming of opening her own studio, but the journey itself mattered more to her now than it used to. While she fought for her life, Palma thought, if she survived, how could she truly give her dream the best shot possible? And where could she find real meaning along the way?

She remembered her dad always told her never to forget where she came from, and the dream-on-the-way-to-the-dream came into focus. She wanted her journey to reflect her love for her family, too.

My dream was to be the first person in my family to go to college. My sister told me the other day, ‘You know what? You’re living a dream for all of us.’

Alejandra Palma

BS business administration, Purdue Global

An education to move her forward

“In my country, going to college is a privilege; it’s not a right,” she says. “For a middle-class family in Chile, it’s just not possible. So, my dream was to be the first person in my family to go to college. My sister told me the other day, ‘You know what? You’re living a dream for all of us.’ Living that dream is my gift to myself for being in remission.”

Once she’d made the decision to enroll in a bachelor’s program after a 20-odd-year hiatus from academics, she says Purdue’s reputation made Purdue Global her top pick. The flexibility offered in a program designed for working adults made it a real possibility.

“I chose Purdue Global because I wanted to be part of Purdue. I didn’t want any other university,” she says. “And I wanted an online program because I can work and pursue my degree. It’s been the perfect combination between traditional studies and modern skills offered by the digital age.”

Palma says it’s the best decision she’s made in her life.

“It’s been essential to prepare my journey through the business world. While it’s true that the art of permanent makeup requires technical skills, running a successful beauty studio requires a deep understanding of business principles,” she says. “Studying marketing opened up a world I was not aware of and provided me with the tools to create a strong brand and target the right audience.”

She’s nearing the end of the course requirements now, and she finds that her dad was right — she’s found peace at this stage in life — but she hasn’t forgotten her promise to bring him along. She and her boyfriend, who has been extremely supportive all along, plan to fly her parents in from Chile to share her commencement ceremony when the day comes.

“I haven’t seen them in three years,” she says. “Just thinking about crossing the stage with my parents there, tears of happiness run down my face.”

It’s never too late to invest in yourself … never forget that every effort you put in brings you one step closer to a brighter and more empowered future.

Alejandra Palma BS business administration, Purdue Global

Never too late

Palma wants people to know that education is a life-changing gift to give yourself. Nothing could be more worth it.

“The value of educating ourselves goes beyond that paper we receive at the end and hang on the wall. This is a transformation. We see doors open for us both personally and professionally,” she says.

“It’s never too late to invest in yourself. You must believe in your potential. Embrace the journey and never forget that every effort you put in brings you one step closer to a brighter and more empowered future. Your dedication will be an inspiration to others who want to pursue their dreams, too.”

Purdue senior hoopers raised the standard

Zach Edey, Mason Gillis and Ethan Morton steer teammates in the right direction

It was a gut-wrenching loss at Indiana for the No. 1-ranked Boilermakers. All losses to the intrastate rival Hoosiers are.

When a reporter in the postgame press conference asked guard Braden Smith to explain a late-game turnover that quelled Purdue’s chance for a last-minute rally, junior center Zach Edey grabbed the microphone from his freshman teammate in the crowded media room in Assembly Hall.

“Just to clarify, that was a big play in a critical moment, but every play is big in a game like this,” Edey said. “I didn’t come out with enough energy and had too many turnovers. It’s not just on him; it is on the entire team.”

In retrospect, Edey’s statement made significant steps toward turning one loss into a long-term victory, hoping that the ultimate dividends could pay off this season in late March and April—14 months after the fact.

That is what leadership looks like, and in a public sense, it was a defining moment in Edey’s incredible Boilermaker career.

Team effort

To use Edey’s word “clarify,” the 7-foot-4 reigning national player of the year has had help in leadership from his four-year teammates Mason Gillis and Ethan Morton. It has been a complementary situation. The senior trio possesses different personalities and perspectives when trying to set the best examples for others to emulate.

“We are very different people,” Edey says. “Mason is OK with having a louder, more in-your-face voice that says what needs to be said. While I have never seen Ethan yell at anyone, he is a great organizer and ensures everyone is in the right place. That’s leadership, too.”

The trio, a crucial part of back-to-back outright Big Ten championship seasons, has adjusted as their roles on the team have changed. Edey was quiet when he came to Purdue in 2020, but as his playing time increased, so did his need to speak out.

“I have had to learn how to speak to people and realize that not everyone can be approached the same way,” Edey says. “Some people are OK with being yelled at; I am that way; it will make me focus more. But some guys on the team will yell back at you in the heat of the moment.

“I am not naturally confrontational, but I will do what it takes in the heat of the moment. If you yell back at me, you better fix it. If you fix it, you’re fine.”

Gillis has more of an alpha dog personality and learned to speak up at a young age. But it didn’t come easy for the New Castle, Indiana, native. At church and other team situations in his youth, others helped Gillis get out of his comfort zone.

“I didn’t want to talk to older people because I didn’t know how to talk to them,” Gillis says. “My mom, sister and dad pushed me by kicking the bird out of the nest. They taught me to smile, look people in the eye, and shake their hands. That was an important first step.”

Gillis admits he likes studying the psychology of why people react the way they do and says it has helped improve his leadership acumen. He is also philosophical about his approach.

“Being comfortable in an area that I was not naturally comfortable helped me to be more comfortable in areas where I already am,” Gillis says.

It makes perfect sense.

For Morton, leadership is about first being present through thick and thin.

“It is about showing up every day, sometimes even when you don’t want to,” Morton says.

“Communicating at different levels, both on and off the court, is important, very important.

It is more complicated than it looks. Everybody on this team is a competitor. Everyone is going to want more. Even Zach, the best player in the country, wants more. It is what makes us great. The most significant difference is the buy-in, as a result of coach (Matt) Paint(er) recruiting great guys. We have so much continuity every year because guys stay here. That helps.

“But effective leadership is harder than it looks.”

Crediting the coaches

In addition to recruiting quality people, Painter and his staff have created an environment where effective leadership is a natural by-product of the coaches’ message.

“Paint is the best in the country at building a great culture,” says Morton, who credits his dad, former major league pitcher, and Morton’s high school coach Matt Clement, for setting the standard. “There is great synergy. When he needs to put his arm around someone, he knows when to do that. When he needs to get on somebody, he does that.”

For Gillis and Morton, who have had a starting role in previous seasons, it has been challenging to see their playing time diminished at times and to start the game on the bench. However, the challenges of earning playing time may have cultivated different leadership skills.

“Mason and I have talked about it,” Morton says. “But it is life. Sometimes you work and do everything you can, and it still doesn’t work exactly as planned.”

That is where the two most important words in leadership for Morton come to the forefront: mental toughness.

“As a leader, you aren’t always going to be in positions you want to be,” says Morton, who, like Edey, is not confrontational by nature. “I don’t like yelling at guys but having the mental toughness to do it when needed, to have a challenging conversation with somebody, is so important.”

Easing the pressure

Pressure and expectations are always present, especially from a team that has struggled in the NCAA Tournament in past years and yearns to make its first trip to the Final Four in 44 years. Navigating through that, too, takes experienced leadership.

“I remind my teammates that it is just a game,” Gillis says. “The media and others emphasize it, which we understand. But when it comes down to it, you shoot the same way in the tournament and have to play as hard as you do in the regular season. We don’t need to change anything. We need to keep it simple, so when things get going fast, we can stay simple and relax.”

Edey shares Gillis’s sentiment and knows the seniors’ steady hand will help the Boilermakers weather the storm ahead.

“Last year, when we lost a game, we got down,” Edey says. “This year, when it has happened, we know we can be the best team in the country. It is better. No one’s confidence has wavered.

“I don’t like or dislike leadership. It is like tying your shoes. It is a necessary function. I like to be in control of things, and being one of the team’s leaders, our role is to try to get everyone to play better.”

It is that simple.

By Alan Karpick, publisher of GoldandBlack.com since 1996.

‘My online degree from Purdue Global gave me the confidence I needed’

Desiré Hunter says her master’s degree in psychology showed her she was capable of so much more.

When Desiré Hunter (MS industrial/organizational psychology ’21, Purdue Global) began entertaining the idea of going back to school, she was in a Target parking lot, waiting for her kids while they shopped. She pulled out her phone, Googled online psychology degrees and found a handful of options. She tapped the first phone number on the list. The person on the other end answered with something rather surprising.

“Purdue Global; how can I help you?”

Hunter thought she was calling a different university. She laughed at the sheer poetry of it because there was something the person on the other end of the line could have no way of knowing.

“I’m from the South, and Purdue is one of the hottest schools that’s talked about where I’m from,” she says, looking back on the exchange. “I always wanted to attend, but I just thought I wasn’t smart enough.”

Hunter felt like it was a sign from God.

By the end of the conversation, her path forward was clear.

When you look back and realize you went from ‘I don’t know if I can ever do this’ to ‘I did it,’ you know you can do anything.

Desiré Hunter

MS psychology ’21, Purdue Global

A steppingstone for her whole family in one online program

But the journey to that Target parking lot, so to speak, was a long one. She’d pictured things going a little differently for her life. One thing, however, was never in doubt.

The mom of four says, “My greatest dream is that I always wanted to be a mom. I grew up in a family with four kids; that dynamic was my norm. I could never imagine having one or two!”

“I love that they’re all unique. I used to write things about them. I would say, ‘God blessed me with four angels who are leaders.’ I love that they own their brilliance.”

During a devastating divorce that took two years to finalize, Hunter and her kids relocated to Chicago from their home in rural Mississippi. There, she found herself working with youth on the west side of Chicago, coaching them on their career goals. But one day, to direct her students toward their gut instincts, she posed a scenario. If someone woke them out of a dead sleep and asked them what one thing they wanted to do in life, what would they say?

It was … well, effective. The question wouldn’t leave her mind, long after work was done for the day.

“I found myself asking the same question. What would I do?” she says.

Having grown up in an area where people didn’t have a lot of career options, Hunter found it deeply meaningful to be able to connect with people and help them better understand their true calling, and then point them in the right direction.

And yet, it felt like something was missing. So she went back to her roots. As a kid, she’d always wanted to be a psychologist. But her interests shifted when she got older, and she earned her bachelor’s in business from the University of Southern Mississippi. Once she reentered the workforce after staying home with her kids, she found that social services put her interests and skill set to work together.

She definitely wasn’t on the wrong track. But maybe, Hunter thought, it was time to take it to the next level. She loved helping people figure out where to start in a career, but why stop at the starting line? Why not see it all the way through?

“I wanted to learn to really dig deeper with people,” she says. “Connect with them on a higher level so they can thrive in their workplaces,” she says. “I wanted to help them accomplish their goals.”

That’s when she had a date with destiny in a Target parking lot.

She talked with the Purdue Global admissions counselor about how a master’s in industrial/organizational psychology would neatly pull together all the right things — her backgrounds in business and social services. Her fascination with how the mind works. Her talent for helping people find the right career path and thrive in it.

“That was a Saturday,” she says. “I had everything I needed to start making decisions on Monday.”

How a working student and single mom learned to believe

Back when she first moved to Chicago, Hunter had to contend with a 14-year gap in her resumé (from when she stayed home with her kids). If the bare-bones resumé, the end of her marriage and the move to one of the biggest cities in the country weren’t enough to make her doubt herself, the interviews with potential employers did it.

After hearing employers say that her work experience wasn’t enough, she made a decision. “I just started saying yes to some things,” she says. “And the more things I said yes to, the more I started having wins along the way. It helped encourage me to believe in myself.”

And now, working toward an online degree backed by a university she never realized she was smart enough to attend, she was seeing in real time she could do more than she knew. But a friend pointed out something important.

“They told me, ‘Desiré, you accomplish these goals, but as soon as you accomplish them, you go right into the next without celebrating your successes.’ I always kept moving because I felt like if I stopped to celebrate, I’d lose my momentum,” she says.

That’s not what happened. Stopping to celebrate would keep up Hunter’s spirits and motivate her to keep pressing on when things got stressful. And it was a reminder that her accomplishments were worthy of respect. It forced her to remember the wins. Point to them. Count them. Build on them.

“I used to take myself out,” she says, smiling. “I used to get a slice of key lime pie because it’s my favorite. Now I do things that are creative. I learned how to draw. I make videos. Sometimes I help someone, show some act of kindness. I write handwritten letters — scribbles and all — because those are things that feed the soul for me.”

Now that she has her master’s degree in hand, she says her hard work has given her the gift of evidence — proof that she’s a force to be reckoned with.

“No matter what you’re experiencing, you can do anything,” she says, tearing up. “When you look back and realize you went from ‘I don’t know if I can ever do this’ to ‘I did it,’ you know you can do anything.

“I encourage other moms to let go of the idea that you’re going to harm your children’s futures by trying to secure yours. As a mom, you often think if you take time away from your kids, you’re damaging them. You’re actually giving to them. I’m giving to my kids because I’ll get older someday. And the more I do for myself now, the less they’ll have to do for me then.”

Setting up for success at the intersection of technology and finance

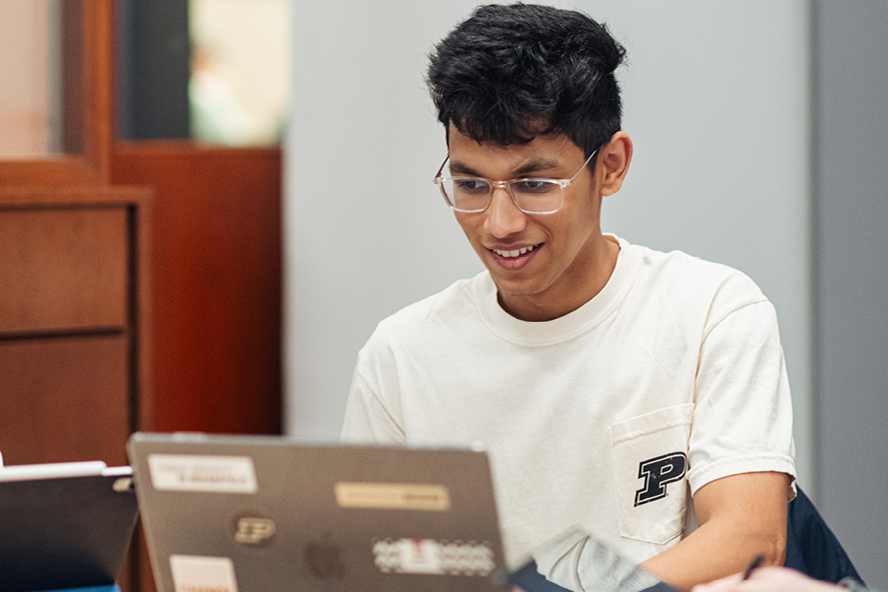

Nikhil Anand Dhoka is excelling as a Purdue computer science and mathematics student in Indianapolis

For Nikhil Anand Dhoka, earning an A-plus is not about the grade. It’s about the ability to build skills and train for a world that’s ever evolving.

“I know that things will change so quickly in the roles that I’m in,” says Dhoka, a Purdue computer science and mathematics student in Indianapolis. “It’s why I think it’s important to be adaptable to new possibilities.”

Emerging fields in computer science can be challenging to forecast, but he’s building the abilities he’ll need to succeed now. He’s committed to always learning something new and seeking opportunities, setting the foundation for an exciting career in technology.

Receiving a perfect 100 score on the final exam is a byproduct of the greater motivation at play.

“It’s really not about the grade,” he says. “I know that when I push myself to achieve more, I’m preparing for learning and self-teaching throughout my life.”

Selecting computer science in Indianapolis

Blending technology and business is the perfect path for Dhoka, who has long-standing interests in each industry.

“I have always been fascinated by technology,” he says. “I remember my first interaction with impressive technology was when my father imported the iPhone 3G around 2008. That was the first time I interacted with a touch-screen mobile phone.”

Ever since, he’s been interested in learning how things work. “I’ve always asked a lot of questions,” he says. “How does technology interact with your fingers? How does it affect your user experience? How can it be better?”

In high school, he became more interested in business and realized that working on the finance side of the technology world would be his most ideal fit. He started searching for universities and came across Purdue.

“Obviously, Purdue stuck out to me,” he says. “It established the first computer science department in the United States. It is consistently ranked as a top program. It made my decision easy.” Coming from Pune, a large city in western India, he was looking for an urban environment that could offer new connections.

“I knew some people that went to Purdue, so I was aware from them that I would be getting an excellent education as well as a vast number of opportunities,” he says. “That was really meaningful and made me choose to go here over other schools.”

Obviously, Purdue stuck out to me. It established the first computer science department in the United States.

Nikhil Anand Dhoka Purdue computer science student in Indianapolis

Leaning into lifelong learning

A degree in computer science with a minor in mathematics is the result of careful consideration and collaboration with academic advisors.

“I need to understand fundamentals in order to work on the finance side of tech,” Dhoka says. “How is software built? How do products work internally? How can I help make scalable applications? I want a well-rounded understanding.”

Growing up, he learned through resources he sought out himself in his spare time, like watching YouTube videos to find out more about financial markets and banking principles. Now he’s able to collaborate with faculty and students to expand his knowledge.

“Even though I’m only in my second year, I’ve had so many hands-on projects here,” he says. “My professors and teaching assistants have been really helpful in navigating the intricacies that come with these technologies.”

It’s been rewarding to connect learning principles to real-world applications. In one of his courses, he developed a virtual auction house via Java’s object-oriented programming language, which allowed users to log in and experience all of the components of an in-person auction — including an effective timer and responsive bidding system.

Between classes, Dhoka is a software engineering researcher. Last year, he worked with a group of peers and mentors to develop an augmented reality (AR) platform using programming languages and a 3D-printed headset. The platform was designed to provide tutorials for visual and tactile learners. Together, the group explored ways that AR and virtual reality can enhance education.

Finding ways to connect

Outside of classes and research, Dhoka has met people through his involvement in student organizations. He finds that much of his schedule is spent on campus, from studying in the Honors College lounge at the library to meeting with the Computer Science Club, where he serves as treasurer.

He’s also the chief technology officer for the undergraduate student government and the graduate and professional student government. Through collaborating with students, faculty and staff, including IT professionals and security experts, he’s able to introduce bills that bring innovative digital tools, platforms and applications to the university.

Everything’s building a base for life after graduation.

Nikhil Anand Dhoka

Purdue computer science student in Indianapolis

Off campus, Dhoka loves living downtown. His favorite part about Indianapolis? The fact that everywhere he turns, he finds a new opportunity. Coming to the university at age 17 was his first time in the U.S., and he’s created a home for himself through networking.

“It’s been amazing,” he says. “If I search something I’m interested in on the internet, there are ways to get involved. If I want to network, there are people not only at school, but around Indy.”

There’s always something to explore. He believes that pushing himself to continually learn and reach out to new people will pay off.

“I’m getting the experience that I came for,” he says. “Everything’s building a base for life after graduation.”

Meet Purdue Global professor Josef Vice: Why your success matters

He’s devoted his life to providing students with the safety, support and odds for success that he didn’t have

Raised in rural Alabama, Purdue Global English and rhetoric professor Josef Vice says if he can make a comeback, so can other working adults.

I fully believe that writing is putting yourself on a page. It’s vulnerable. A lot of students don’t want to do it. But if they can see they have something worth sharing, they can see they have something worth hearing.

One of the things I do to help students build confidence is talk about challenges. Lately, I’ve been telling them about my doctoral degree. I completed all my coursework in 1987, but my dissertation never got off the ground. I wanted to write about something relevant to LGBTQ+ issues. I knew that wasn’t of much academic interest at the time, so I proposed writing about the concept of “the outsider” in medieval literature. I was looking at Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales” — some characters have less binary gender and sexual identities, so maybe there was something there. I was shot down immediately.

At the same time, I was very involved in petitioning the university to allow us to create a student LGBTQ+ group. To rally support, I came out in a letter published in the school newspaper. I argued for equality: We’re your friends. Your family. Your teachers.

I felt like my recent comeback was a reclamation of what should have been. I got to reach back 35 years and finish the doctorate I couldn’t finish at the time.

Josef Vice

Professor, Purdue Global

We won in the end. But when the letter was published, I lost my assistantship. I was also teaching part time at a local community college, and I was fired from that, too. They said it didn’t align with their morality clause. In that climate, writing a dissertation on what mattered to me seemed impossible.

I felt like my recent comeback was a reclamation of what should have been. I got to reach back 35 years and finish the doctorate I couldn’t finish at the time. It energized me. It gave me a real sense that this is something that should be written about, researched and embraced by an academic community.

A lot of my students have faced setbacks, but they’re here, giving it another try. I get to share my story with them and tell them it’s never too late. You don’t have to give up on that dream. There’s a good fight out there, and whatever you’ve been through, you can come back. Your dream is worth it.

It’s never too late. You don’t have to give up on that dream. … Whatever you’ve been through, you can come back. Your dream is worth it.

Josef Vice Professor, Purdue Global

Black pioneers who shaped Purdue Athletics

Five Boilermakers reflect on what it was like to be a Black student-athlete at Purdue

Pioneers.

There have been many in Purdue Athletics history. But perhaps none more important than those among the first Black student-athletes to compete for the Boilermakers.

The list of five former Black Purdue student-athletes below is just a sample of the stories of many who forged their path. Each agrees that Black History Month is the time to honor and celebrate the diverse experiences and perspectives of their time at Purdue. It is also time to educate.

“I think the celebration of all history is important, and it is important at least for one month that people take the opportunity to study our Black heritage, our culture,” says Roland Parrish, a standout track athlete at Purdue from 1971-75.

“We all had experiences, and we all had challenges.”

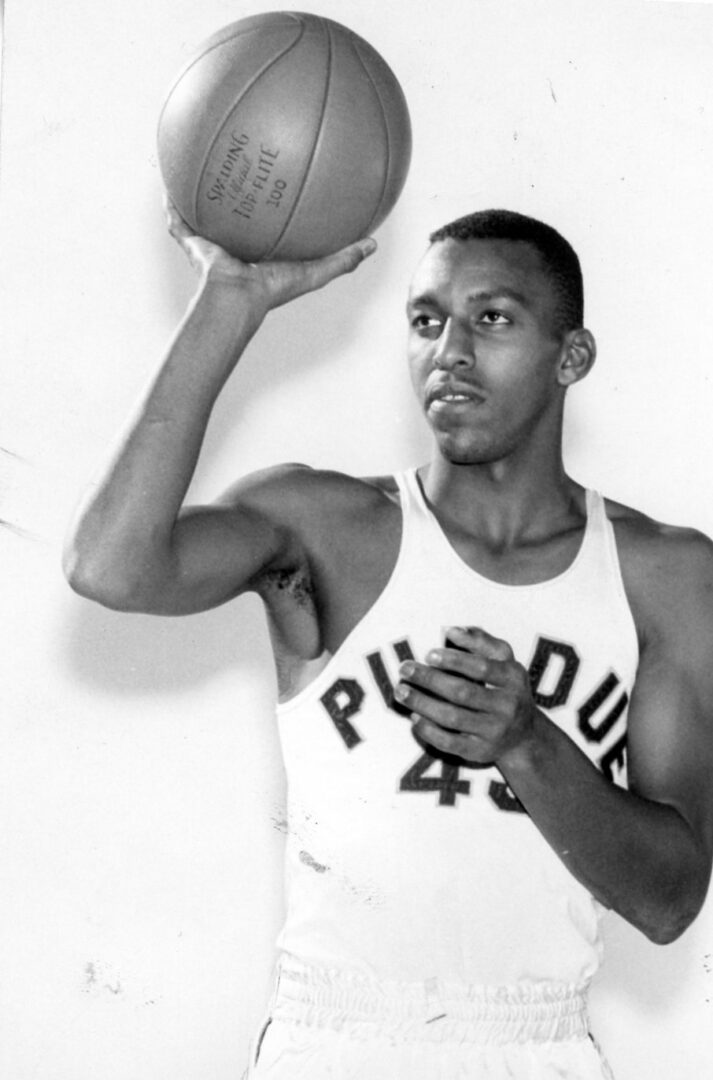

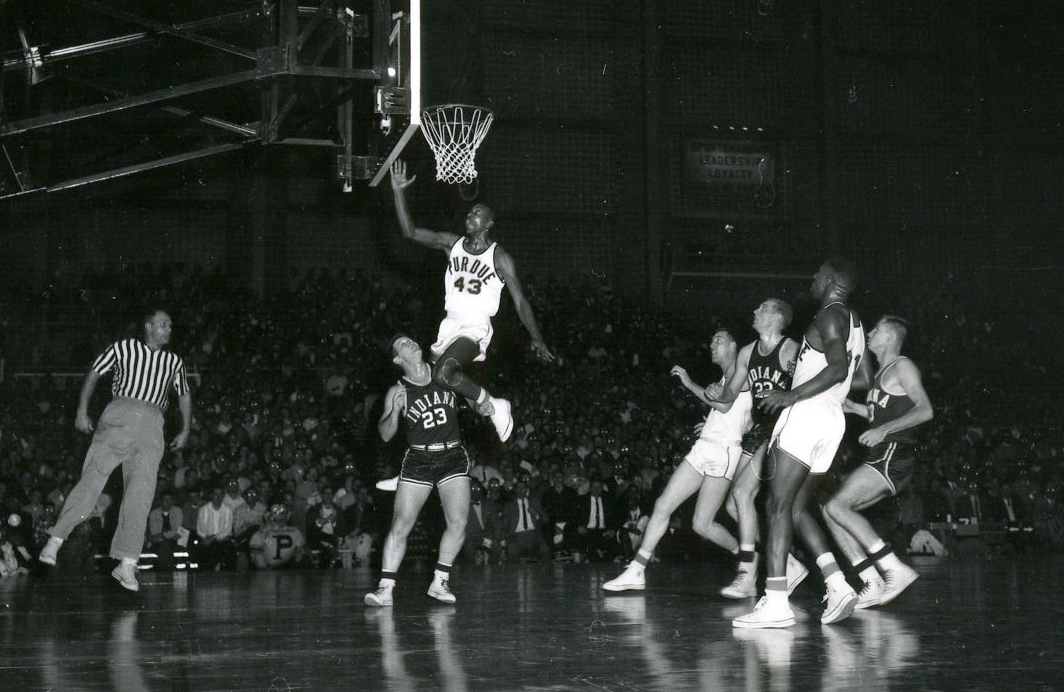

Willie Merriweather, men’s basketball, 1957-59

A teammate of Oscar Robertson at Crispus Attucks High School, Merriweather was a standout player for coach Ray Eddy. He was good enough to be inducted into the Purdue Athletics Hall of Fame, averaging 20 points per contest in his senior year. He played at Purdue during the first large influx of Black basketball players, crossing paths with Lamar Lundy, Wilson “Jake“ Eison, Harvey Austin and Charlie Lyons.

“It was great to have those guys as teammates, and I had a good experience at Purdue,” says Merriweather, who went on to have a four-decade career as an educator in Detroit. “We were treated well as athletes. We adjusted to how things were then, even when told by Coach Eddy that they couldn’t simultaneously play more than a couple of us (African Americans).”

Socializing was not easy for Black people on Purdue’s campus in the 1950s, when students of different races were not treated equally.

“So we focused on our studies, and I was proud to make the dean’s list,” Merriweather says. “It meant a lot to me to be a good student.”

Merriweather has enjoyed watching all the changes that have occurred for Black athletes and all athletes in the past 60 years.

“It’s a whole different world today for the kids,” Merriweather says. “I am glad most people celebrate our history. It’s not perfect by any means, but having the opportunity to play when I did, I had some role in making things better for those that came after me.”

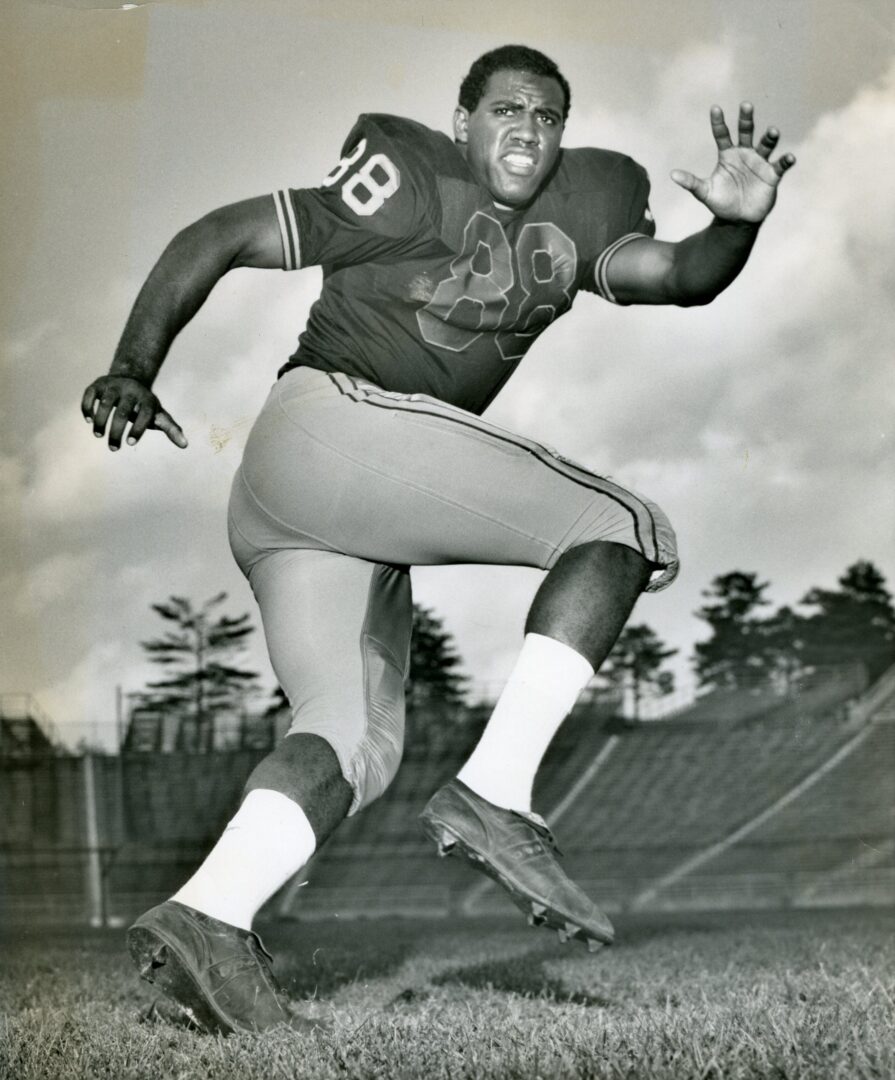

Billy McKoy, football, 1966-69

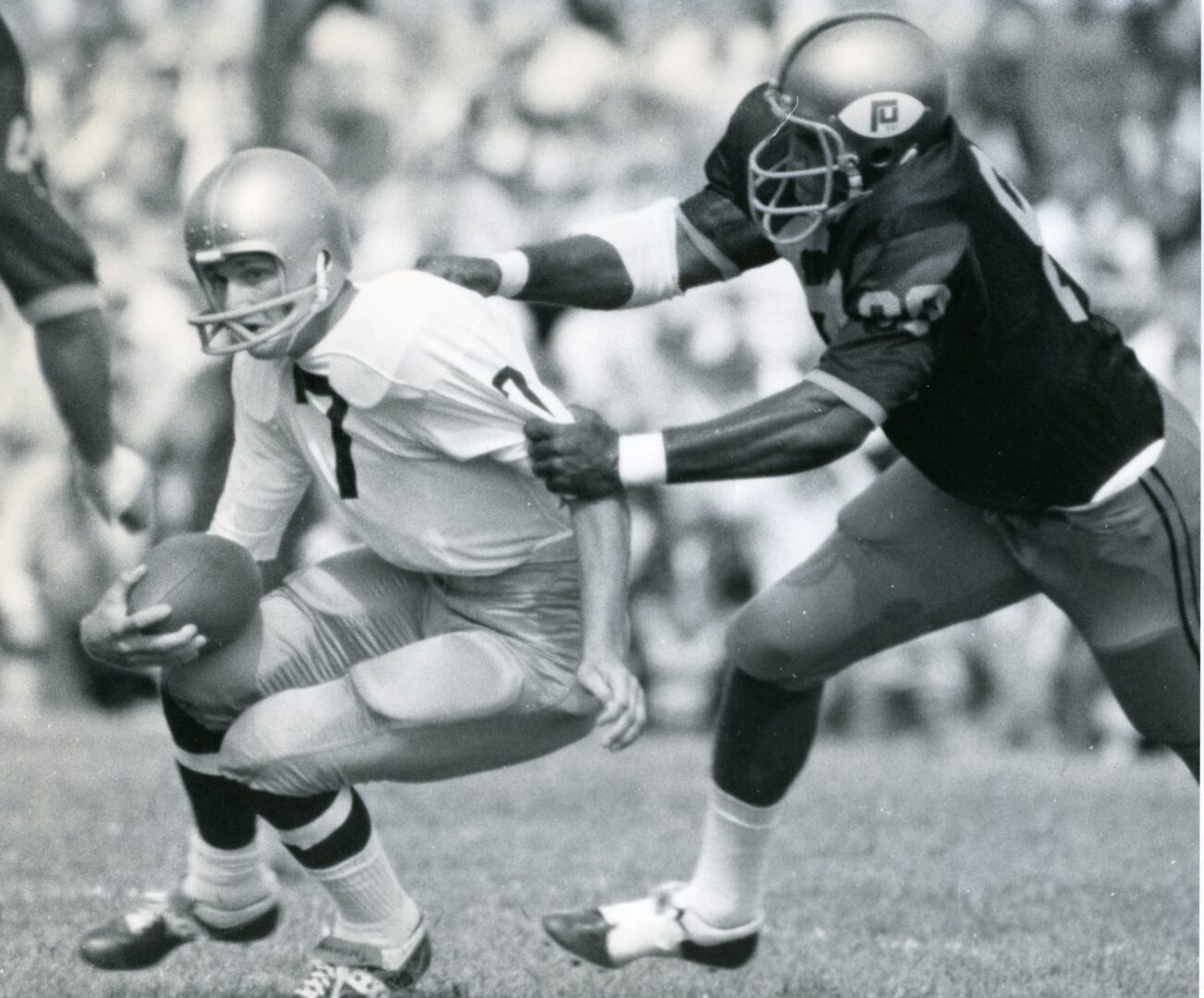

William (Billy) McKoy was a standout defensive end for coach Jack Mollenkopf and played for Boilermaker teams that compiled a 24-6 record from 1967-69 and won a Big Ten championship. Additionally, he was part of the first program in college football to beat Notre Dame three consecutive seasons.

Coming to Purdue from the segregated South was initially a shock for McKoy, a native of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The same school had produced Herman Gilliam to Purdue a year earlier. Purdue football had been integrated in the 1950s and produced Lamar Lundy, the only Boilermaker to earn MVP honors in football and basketball in the same school year.

“I credit my good experience to Coach Mollenkopf because the team was like a family, and he created that environment,” says McKoy, who went on to play in the NFL for the Denver Broncos. “It was seamless. Despite the racially charged times, our team had no racial hiccups.”

The environment on campus was mostly a positive experience for McKoy, although he recalls a few unpleasant interactions with fellow residents of Wiley Hall and professors who didn’t always embrace his perspective.

“My high school teachers had me ready for college, so I was confident I could do college work,” says McKoy, who ended up with a several-decade career in human resources and as senior vice president for operations at the YMCA in Atlanta. “But it was an adjustment for all of us.”

The importance of Black History Month is not lost on McKoy.

“I am a glass half-full person, but there are some places where people are trying to change the narrative of our history, and that is concerning to me as it should be to everyone,” McKoy says. “It remains unfortunate that we are still hearing too many times, ‘This is the first African American to do this, this is the first African American to do that.’ I thought we might be further along in my lifetime.”

McKoy cites one of his best moments as his long-time relationship with a teammate who had never met a Black person before he came to Purdue.

“The fact that we are still friends today is important to me,” McKoy says. “One of the things about ‘ball’ is you had to figure out how to win the game that was in front of you. Winning, however you define it, was what it was all about. That helped me survive and thrive at Purdue.”

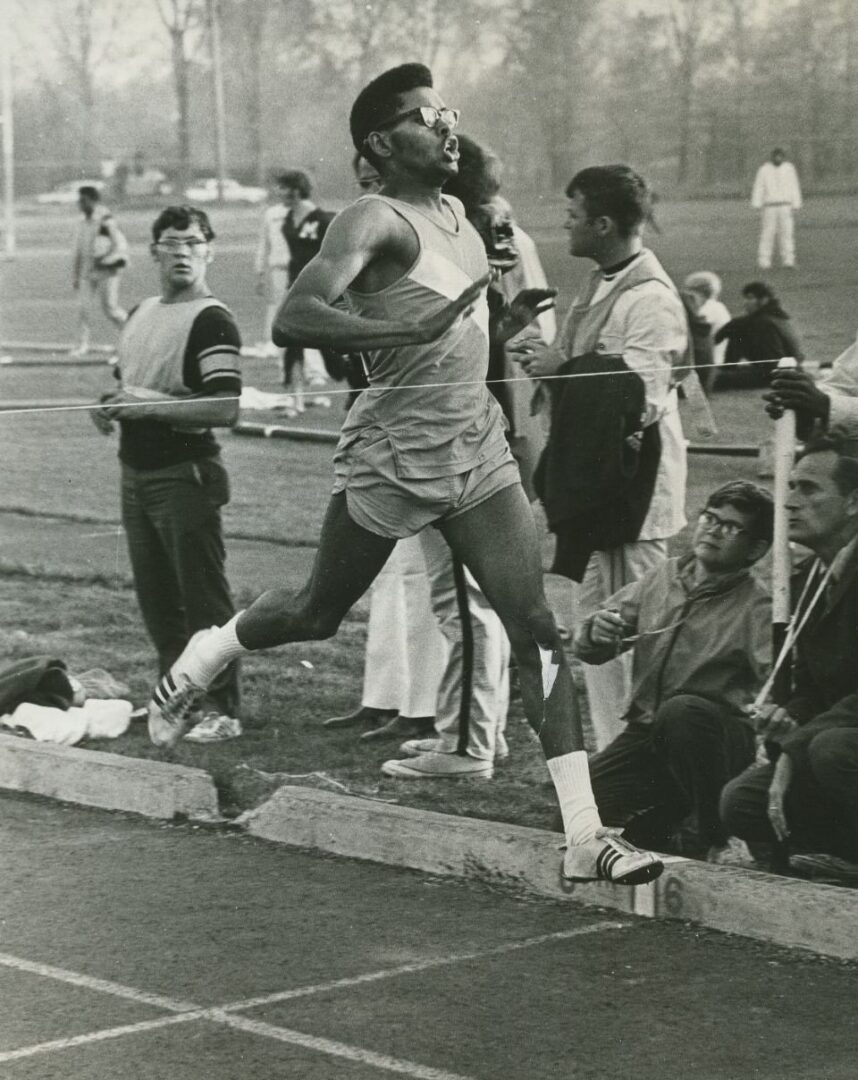

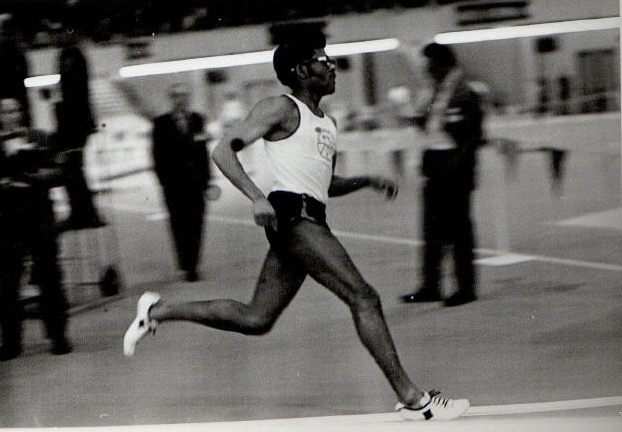

Roland Parrish, men’s track & field, 1971-75

A native of Hammond, Indiana, Parrish came to Purdue on a full-ride track scholarship. After growing up in a Black neighborhood, the middle-distance runner attended Hammond High School, which was only about 3% Black.

“Coming to Purdue wasn’t the culture shock for me as it was for many people of color,” says Parrish, who was voted team captain and twice earned team MVP honors. “Back then we didn’t have Black coaches for mentors, but I was very fortunate to have Dr. Cornell Bell, the head of Purdue’s Business Opportunity Program (BOP). He was a no-nonsense man who didn’t let you make excuses.”

Parrish credits Bell and others for helping him be disciplined. He studied, went to track practice and was a musician for the Second Baptist Church in Lafayette, where he played keyboard on weekends.

“I believe in the saying, ‘The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing,” Parrish says. “When I break it all down, it is really that simple.”

In Parrish’s mind, Black History Month is a time to recognize the people that came before. In athletics, Parrish was forever touched by the life and times of Leroy Keyes, Purdue’s two-time All-American football player who came to campus six years before Parrish.

“I always looked up to Leroy and I stand on the shoulders of those who walked in my shoes when things weren’t quite as evolved as they were when I was in school,” Parrish says. “Even 40-plus years later, Purdue continues to evolve. I like what I see out of the university regarding race, but there are always paths to travel for improvement.”

Parrish has had a stellar business career, which includes owning more than two dozen McDonald’s franchises in North Texas near his Dallas home. He has given time and treasure back to Purdue in many areas, including funding a renovation of the former Management and Economic Library a dozen years ago. He has also funded a scholarship in Bell’s memory and remains devoted to the Keyes family after Keyes’ passing in 2021.

“There were challenges for Blacks when I was at Purdue,” Parrish says. “But I look at all the programs available to Black kids today and all the role models that Purdue’s athletes have access to, and that makes me hopeful that we are making progress.”

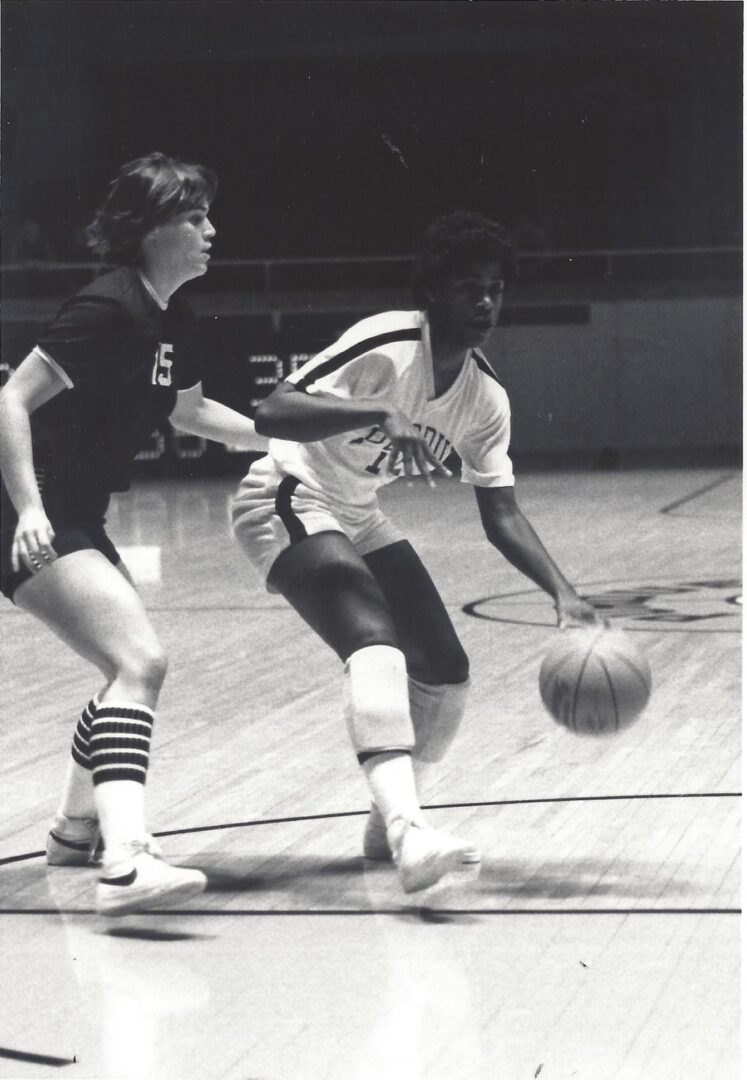

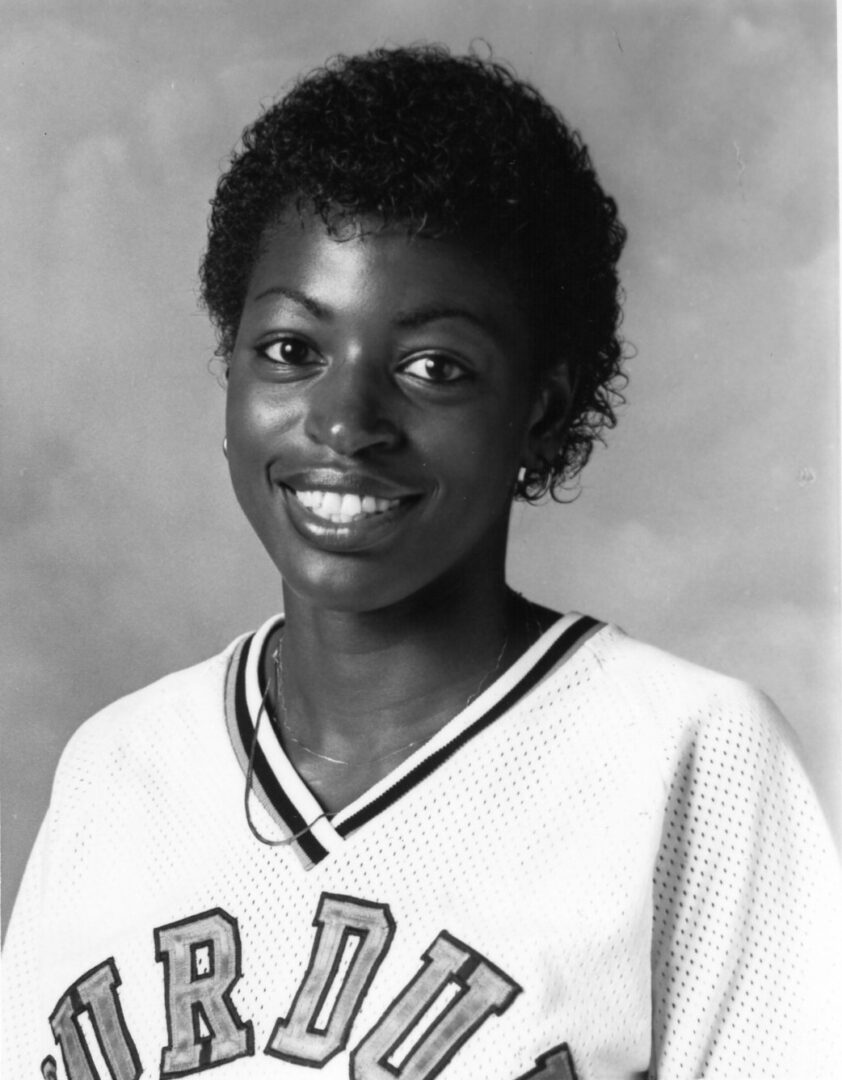

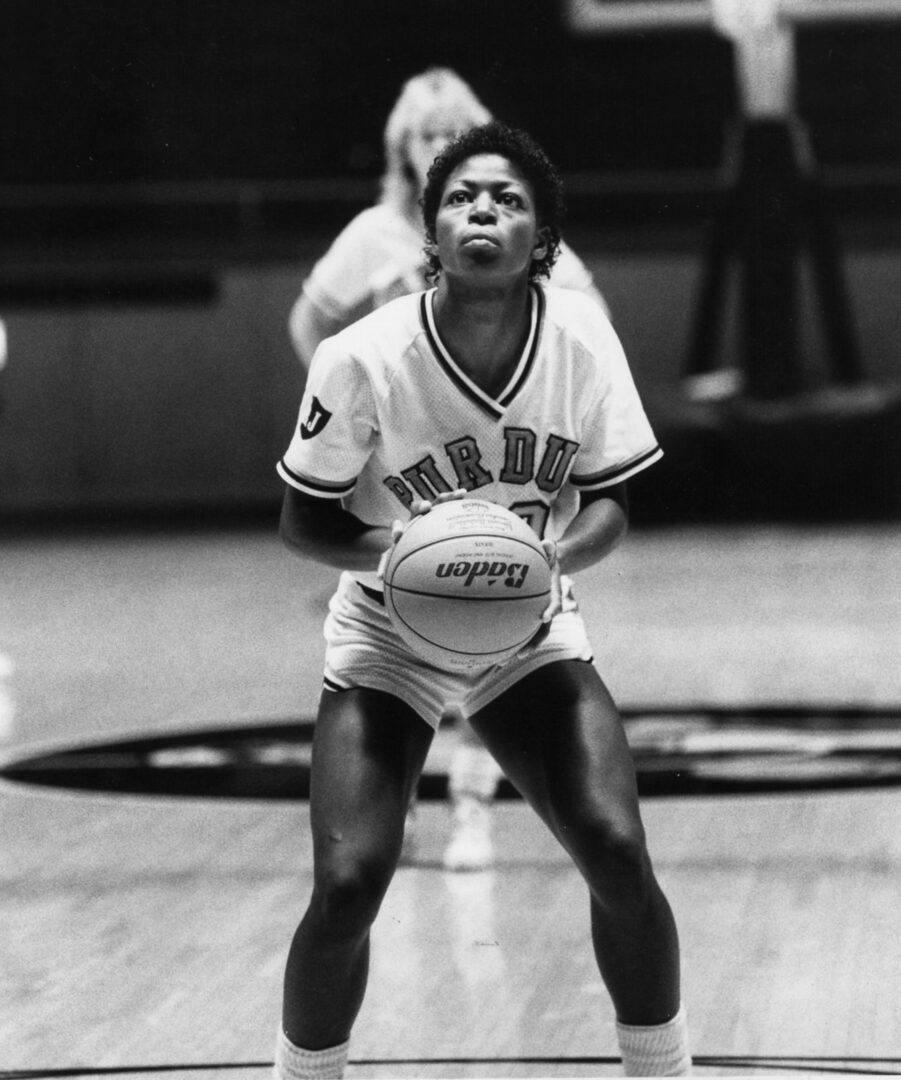

Pat Harris, women’s basketball, 1979-82

The study of Black history has to be more than one month. My message to kids is: ‘Learn how we got here and volunteer.’

Pat Harris

Purdue women’s basketball (1979-82)

With a reputation for calling it as she sees it, Harris is happy to embrace her trailblazer status in the history of the Boilermaker women’s basketball program. She admits she was as much a pioneer in women’s sports as a Black athlete at Purdue.

“Because women’s basketball was still in its infancy when I came to Purdue (it began officially in 1975-76), I guess you can call me a pioneer,” Harris says. “Women’s sports weren’t embraced by the athletic administration at the time.