Meet Purdue Global professor Nelly Mulleneaux, proud military spouse

With a drive to introduce others to the opportunities education presents, this tech professor knows how to support students

Nelly Mulleneaux is Purdue Global professor in technology and the spouse of a retired U.S. Army veteran. She’s a recipient of the Yellow Rose of Texas award for her powerful advocacy for, and empowerment of, students and military families. Here, she speaks on her experience as a military spouse and how it guides her philosophy on education.

Deployment, for the partner and family left behind, is a singular type of loss. They carry the grief, but they can’t move on. The place they call home becomes an empty shell where they put their lives on hold until their service member returns. Moving around, leaving family and friends behind was a difficult part of my experience, but the most challenging thing was to see him prepare for deployment and then go.

One of the byproducts of my experience with my husband’s deployment, however, was the empathy it built in me. As a professor, I see all kinds of situations that deserve a tailored approach. I love encouraging students to use a difficult situation, like the deployment of a spouse, as a time to grow something for themselves. Military life doesn’t last forever, and it’s essential to have the capacity to plan for the future.

I’m proud to work for a university that is honored to support students when they have time constraints due to their military requirements. Our military students model incredible commitment. We have students doing work using their phones. They’re planning ahead. They’re devoted to the mission, which always comes first. Purdue Global faculty will always work with our service members and their families. We want them to be successful in putting their future in motion, even as they take on one of the most challenging roles in our nation — serving as a member of the U.S. military.

I love encouraging students to use a difficult situation, like the deployment of a spouse, as a time to grow something for themselves.

Nelly Mulleneaux Professor, Purdue Global

‘My family is everything, and I won’t let the past hold us back’

Amber Martin created opportunities for herself and her family with a psychology degree from Purdue Global

Her family would say that Amber Martin (MS psychology ’21, Purdue Global) is one of the busiest people they know.

She routinely balances jobs, her five kids’ extracurriculars, their homework and her own homework. She started her master’s degree with Purdue Global when the youngest of her children was 6 months old — the same year her oldest graduated high school. Add to that: Right now, she’s halfway through her Juris Doctor at Purdue Global Law School.

But they’ll also attest to the fact that she always finds time to paint a bedroom if one of the kids expresses a new vision for their space. She doesn’t consider herself too busy to host and cook holiday dinners with her husband, Seth, for their extended family and friends, often upward of 20 people. Or help her fellow football parents serve breakfast for the entire varsity team the morning after a game. Or help her in-laws move, or jump start her brother-in-law’s car.

If that list gives you heart palpitations, you’re not alone. She gets asked all the time: “How in the world can you make all that happen? What keeps you going?”

She has one response: Her whole life, as she explored many different careers, the single constant was her dream of raising empowered kids. And now it’s a dream she shares with Seth. For them, everything goes back to that.

“I don’t want it to be me, the reason the two of us would have to say no to things they want to try. I don’t want their dreams to be quashed because I couldn’t contribute enough,” she says.

When she looked at her work and felt stuck, she saw opportunities. One, she could make a move that would boost their combined income and help provide the kids with a world full of options. And two, she could show them what it looks like to deal with your ghosts and get yourself unstuck.

I don’t want … to be the reason we’d have to say no to things my kids want to try. I don’t want their dreams to be quashed because I couldn’t contribute enough.

Amber Martin

MS psychology ’21, Purdue Global

JD ’25, Purdue Global Law School

Building a family and a future

The journey that led Amber to Purdue Global involved a lot of pit stops.

Choosing her major out of high school was easy. She’d always been fascinated by psychology, so at 17, she decisively chose her major. She planned to earn her bachelor’s in psychology and then move on to grad school.

When she discussed her plans to earn a master’s degree in psychology with her academic advisor, she trusted she’d be guided toward resources for the application process. Or advised to take one course over another, or maybe receive recommendations for entrance exam texts to study for.

She gave Amber none of those things. Unbelievably, the advisor dismissed her plan without explanation.

Taken aback and feeling utterly betrayed, 20-year-old Amber threw her whole plan away and found comfort in a new major — theater. She’d always had a love for plays and movies, and a shift to something more lighthearted provided relief.

In the meantime, she was waiting tables to pay the bills. That’s where, after enduring such a blatant display of disapproval from her advisor, Amber found her biggest cheerleader.

Seth was her manager. When Amber graduated with her theater degree, she became a manager, too. Then he left to go back to school. Then he came back, and they were both managers.

Then they were more than that.

And ever since, they’ve been a team. Amber credits her ability to accomplish all that she does to his unwavering belief in her and their shared drive to prioritize family over anything else.

“He’s such a strong supporter,” she says. “I’m thankful to have a true partner. Not everyone has that.”

They continued in the restaurant business together, and Amber found a way to carve out a professional niche for herself.

“I worked my way up to a regional director role that included promotions and marketing,” she says. It was the early 2000s, and she took advantage of the moment — websites were just starting to become a necessity for businesses to remain competitive, so Amber learned how to update them.

Then, babies two and three came along.

Team Martin held steady to their goals, and Amber’s tech savvy proved useful. She discovered the world of institutional review boards (IRB), which work to ensure scientific studies of humans are held to a high ethical standard, when she found that a local IRB was looking for help updating their website. The job was hers, but working closely with the IRB’s mission inspired her. She eventually became certified as an IRB professional herself, but even so, Amber started to realize she’d need a master’s degree to continue moving forward.

Then, babies four and five.

Finally, in 2019, when their oldest started her own college degree, Amber landed on a plan. By then, she’d realized she was being haunted by the ghost of the psychology degree she never finished. She knew what she had to do.

“I don’t like people telling me I can’t do things,” Amber says. “But when I’m told I can’t do something, it gives me the motivation to prove them wrong.”

It was time.

I asked myself, ‘Why can’t I do this? What’s stopping me from studying psychology?’

Amber Martin MS psychology ’21, Purdue Global

JD ’25, Purdue Global Law School

A master’s degree to move her forward

Purdue Global was at the top of her list. The master’s program in psychology looked doable for a working adult, run by highly skilled faculty and backed by a respected university — all major selling points for her.

“I asked myself, ‘Why can’t I do this? What’s stopping me from studying psychology?’” Her journey had taken her across different kinds of work, but maybe she could lean into the multidisciplinary nature of her resume.

“Forensic psychology interested me because it’s not just helping to solve crimes, like you’d see on TV,” she says. “You have a lot of options, like serving at state institutions or as an expert for family court and speak to what you know about relationships, and how those things affect children developmentally.”

This degree from Purdue Global would pull together all her experience. The public speaking from theater. The people skills from waiting tables and managing restaurants. The ability to assess the quality and ethics of research processes, along with their effects on people, which she developed working with IRBs. Even the experiential understanding of child development she’d earned from parenting five kids.

‘You can change your mind’

As she neared graduation, she wondered what was next, until Seth suggested Purdue Global Law School. The idea didn’t click right away — she couldn’t picture herself as a litigator — but he held steady in his belief that she’d be great at it.

Eventually, she started to see what he meant. Her degree in forensic psychology dovetailed nicely into law, and career path options were not limited to litigation. In fact, it built on what they were trying to accomplish all along — keeping as many options open as possible. Understanding of the law would only expand what she could do.

“It’s exciting to know it’s not lost, what I worked so hard for,” she says.

And she pushes forward, both inspired by her family and empowered by them.

“Seth and I want the kids to be able to achieve everything they want to achieve and have the world open to them,” she says. “We try to teach by example. I want to show them that they don’t have to settle with one thing or another, and if they change their minds, if they want to go from theater to forensic psychology to law, they can do it and be successful.”

Community involvement inspires student at Purdue University in Indianapolis

Sarah Papabathini is making a difference every day — as a mentor, researcher, volunteer, princess and AI major

When your schedule is as packed as Sarah Papabathini’s, only a pink weekly planner can contain it. “My planner is the Holy Grail,” she says. “I carry it with me everywhere and am constantly referring to it. Always asking myself, ‘OK, what’s next?’”

It turns out that “what’s next” is quite a lot. Papabathini, a Purdue AI student in Indianapolis, takes advantage of all the city and university have to offer, whether it’s community engagement, academic research or just fun with friends.

Indianapolis involvement

Growing up in Chicago, Papabathini learned firsthand the value of meaningful after-school activities. “My dad worked late when I was younger, so I was enrolled in after-school programs,” she says. “I really appreciate what they did for me and am especially grateful for the people who helped run them.”

It was a given for Papabathini that she would pay that gratitude forward by becoming involved in her college community. “I’m a mentor within high schools and middle schools here in the Indianapolis area,” she says. “I stay in regular contact with my students — meeting with them in person, sending them texts, asking about their days. I especially like to check in when I know they have a test or a big assignment.”

Papabathini started volunteering with DREAM Alive — a youth mentorship program founded by former Indianapolis Colts offensive tackle Tarik Glenn and his wife, Maya — during her first year at Purdue in Indianapolis. DREAM Alive is incredibly successful; it has a 100% high school graduation rate for participants.

“This program encompasses so much,” she explains. “We play games and do activities together when classes are over, but we also have lunch and learn during the day.”

Mentors eat a meal with students and then lead a lesson about career and educational opportunities or topics such as mental health and how to identify a trusted adult. “We’re trying to help them imagine their futures,” she says.

Papabathini’s Indianapolis involvements also gave her a chance at becoming something unexpected — royalty.

I am so proud of where I live and of my university. I am excited to talk up Indianapolis, the 500 Festival and Purdue in Indianapolis with everyone I meet.

Sarah Papabathini Purdue AI student in Indianapolis

500 Festival princess

As a 500 Festival princess, Papabathini has distinguished herself as one of Indiana’s most community-oriented and academically accomplished young women. She is responsible for being an ambassador for the festival and for Purdue in Indianapolis. It’s a role she leans into.

“There are 33 wonderful women who have been selected this year,” she says. “We all get to do exciting community outreach.”

One of Papabathini’s favorite activities is going to local elementary schools and “spreading the magic of the Indy 500.” She especially appreciates that this program allows students to have experiences that might not otherwise be available to them.

“We get to bring a pace car to students who likely wouldn’t have the chance to see one,” she says. “We get to show them what drivers wear. It’s so much fun, especially for kids who live a bit farther away and those who don’t get to come to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. It’s cool to bring some of that experience to them.”

Papabathini is enthusiastic about sharing her love of Indiana with others. “I am so proud of where I live and of my university,” she says. “I am excited to talk up Indianapolis, the 500 Festival and Purdue in Indianapolis with everyone I meet.” As busy as she is in her city, Papabathini is just as immersed in life on campus.

Clubs and organizations

Papabathini’s interest in extracurricular activities at Purdue in Indianapolis ignited when she was still a prospective student. Several older cousins, who are alumni, strongly encouraged her to take a campus visit. She was impressed right away.

“My cousins had nothing but great things to say about the university while I was growing up,” she says. “They really encouraged me to visit campus. So when I was in high school, I toured the engineering school and loved it. I actually work in the engineering and technology office now as a peer mentor, student ambassador and at the front desk. It’s very much a full-circle moment.”

One of her primary extracurricular commitments is as vice president for the Indianapolis chapter of the Black Data Processing Associates (BDPA), which is a national organization. “My role within BDPA is connecting local companies in Indianapolis to our chapter here,” she says, “providing students with professional opportunities.”

A recent BDPA event on Purdue’s campus that Papabathini helped organize was an Eli Lilly and Company panel.

“We got some people from Eli Lilly to come to campus and speak with us about what they are looking for in a job candidate. They also discussed resume reviews.”

BDPA leadership meets weekly to discuss upcoming competitions and events. Papabathini, a self-described “people person,” appreciates that the work she does for BDPA connects people.

“I’ve loved forging connections with these great companies here in Indy,” she says. “I appreciate the professional networking that this position has granted me.” In addition to the BDPA, Papabathini is involved in numerous other on-campus clubs and organizations, including the Society of Women Engineers, Women in Technology, the National Society of Black Engineers, Asian Student Union, Black Student Union, Cru ministry, two honor societies and more.

AI and zombies

Papabathini’s campus visit also helped her identify her future major. “After taking the tour, I thought that I could really see myself here, on this campus,” she says. “And my first year was the year the AI program was rolled out.”

Papabathini thought the major sounded interesting. She also noted that there weren’t a lot of other universities offering this type of degree program at the time.

“Introduction to AI my freshman year is what encouraged me to fully dive into the major,” she says. “We had the opportunity to train a system to distinguish between various objects and facial expressions, similar to facial recognition.”

The hands-on learning in her AI class involved training a computer model over and over and over again. “For one project, we were trying to make the program differentiate between a banana and an apple,” she explains. “This involved putting many bananas and apples in front of the machine and trying to get it to correctly say, ‘This is a banana’ or ‘This is an apple.’ My group was pleased to end up with 90% accuracy.”

She is also taking courses like Calculus III, which supports her minor in mathematics, and Neuroscience, where they are mapping parts of the brain to explore structure and function. She especially enjoys her Data Structure class, which is the study of design and analysis of abstract data structures and algorithms.

But it’s not all STEM for Papabathini. She is also taking classes in writing, golf and the zombie apocalypse.

“The title of the class is actually Zombie Apocalypse and Doomsday Infections,” she explains. “During the first half of class we explored various cultures and their representations of zombies. The second half of class looked at infectious diseases and how humanity can survive them.”

I want to see what impact I can make in the field. How can I contribute to the curve and empower learning for everyone? What can I do to contribute to the next evolution in AI?

Sarah Papabathini

Purdue AI student in Indianapolis

Academic research

Zombie apocalypses aside, Papabathini’s experiences in the classroom sparked a desire to conduct research. As a second-year student, she gained career-ready research skills by participating in a multidisciplinary program.

Currently, she is in the Navy Engineering Innovation & Leadership (NEIL) program, which helped prepare her to publish her co-authored research this semester. Every Monday, she meets with her NEIL research advisor to discuss what they have been working on and what stage they are at in their projects. “We also talk about challenges we’ve had,” she says. “It’s really an open meeting to see how we can help each other.”

What next?

From an early age, Papabathini has loved technology. In high school, she participated in the Girls Who Code club, which provided a foundation she has continued to build upon.

“I am interested in exploring the curve for technology,” she says. “Where is AI leading us? What’s on the horizon?”

She says the career possibilities are endless, and she can’t wait to explore them. But as someone who deeply invests in her communities, Papabathini is looking for even more.

“I want to see what impact I can make in the field,” she says. “How can I contribute to the curve and empower learning for everyone? What can I do to contribute to the evolution of AI?” No matter how Papabathini answers those questions, one thing is clear: She’s going to need more pink planners.

From childhood racing fanatic to IndyCar engineer

With strong support from many mentors, motorsports engineering graduate Lizzie Todd is living out her dream as a racing engineer

For the most part, Lizzie Todd’s memories of her first Indianapolis 500 are somewhat hazy.

She remembers watching most of that 2006 race from the railing near her family’s seats because the man sitting in front of her was so tall that 8-year-old Lizzie couldn’t see the track.

She describes her older sister Annie crying because Sam Hornish Jr. won the race, not Marco Andretti, who Annie thought was cute.

And she recalls tracking the leaders on a scorecard every 10 laps, hoping that her favorite drivers like Danica Patrick or Tony Kanaan would emerge victorious.

Alongside those vague recollections, Todd also has a crystal-clear memory from that race week — an inspirational moment that helped racing become a personal passion and, years later, her career.

She remembers arriving late to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway for the Carb Day practice session the Friday before the race. Her dad was annoyed, worrying that their tardiness might prevent the family from getting good seats. But it turned out to be the best thing that could have happened for the precocious 8-year-old passenger in his car.

The green flag fell just as the Todd family vehicle emerged from a tunnel alongside the track, so Lizzie was at eye level with a race car as it rapidly launched into a practice lap.

“This car went from 60 to 220 (mph) in the most insane amount of acceleration that I’d ever seen,” she says. “I never heard an engine like that in my life before, and we were so close that I felt it in my chest. I just fell in love.”

Right then and there, a future race engineer was born.

Todd put in lots of hard work since then — studying, internships, networking, real-world experience — helping her turn a childhood obsession into a position as systems engineer with the Arrow McLaren IndyCar Team. Along the way, she received guidance and support from a mentor she met during an Indy 500 a few years after that influential Carb Day: Terri Talbert-Hatch, co-founder of the IUPUI motorsports engineering program that is now under the Purdue University in Indianapolis umbrella.

A supportive mentor

Todd and Talbert-Hatch’s friendship dates back to Todd’s eighth-grade year, when she emailed one of Talbert-Hatch’s colleagues requesting information on the motorsports engineering program she read about on indycar.com.

Talbert-Hatch responded and eventually invited Todd and her family to a sponsor event at driver Sarah Fisher’s shop during race week. She remembers 14-year-old Lizzie being somewhat timid at the event, afraid of doing something wrong in front of the industry bigwigs in attendance. But she also wanted to take every opportunity to motivate a bright, young go-getter to pursue a career in a business that had long been dominated by men.

“The motorsports engineering program was pretty new at that time, and to get a female especially, I was going to do whatever I could to encourage her,” says Talbert-Hatch, now an adjunct professor with the motorsports engineering program and administration consultant at IndyCar race car builder Dallara.

Such encouragement has become a running theme throughout their relationship.

Each summer during high school, Todd returned to Indianapolis to participate in the program’s Preparing Outstanding Women for Engineering Roles (POWER) camp. The camp typically exposed participants to opportunities with company partners like Rolls-Royce, Allison Transmission, Cummins Inc., or one of the many biomedical engineering companies in the area. But whenever Todd was in attendance, Talbert-Hatch made sure that she also got to meet with motorsports engineering students or participate in a racing-related activity, like the time she got to take a tour of Dallara’s production facility.

There are a lot of full-circle moments between when I think back to middle school to where I am today.

Lizzie Todd (BS motorsports engineering ’20) on the mentorship she has received from Terri Talbert-Hatch since middle school

“Terri has been monumental in helping me get to where I’m at. We still stay in touch, and we’re actually going out to dinner next week,” Todd says. “There are a lot of full-circle moments between when I think back to middle school to where I am today.”

Moments like when Todd decided to enroll in the program, graduating in 2020 from the only ABET-accredited motorsports engineering bachelor’s degree program in the U.S. Or when Talbert-Hatch offered guidance on internships that might help her get a foot in the door in the IndyCar circuit. Or even today, when she provides counsel and emotional support to a former student whose job can be extremely demanding.

“She’s my Indiana mom. That’s what I call her,” Todd says.

“So I just make sure I talk to her as a mom would,” Talbert-Hatch adds. “It’s just being a sounding board and sharing her ups and downs.”

Building experience, making connections

Only 26 years old, Todd has already squeezed a lot of ups into a relatively short time as a racing engineer.

As a college freshman, she was a member of a Society of Women Engineers team that earned a second-place finish at the Purdue Grand Prix. A year later, she began working on the IUPUI racing team, whose Mazda Miata competed in the Sports Car Club of America’s F-Production series.

Looking back on those extensive hands-on experiences, Todd recognizes the importance of other skills she didn’t even realize she was building.

“It mirrored what I do now: a lot of late nights in the shop, a lot of time spent with the same people. You’re building relationships with all these people,” Todd says. “Motorsports is so small that I work with people that I was on the motorsports program and in the motorsports club with every single day, whether they’re on different teams or not, but I see them all the time. It’s been really cool to know that you’ve got friends all across the paddock who went through the same kind of things you did, who went through the same struggles you did in the classroom.”

That’s an endless source of pride for Talbert-Hatch, who says she lives vicariously through the former students she frequently sees as an Indianapolis Motor Speedway regular during teams’ preparations for “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing.”

“It’s so fun in May to walk up and down pit row and say, ‘There’s one of ours, there’s two of ours, there’s three of ours,’” she says.

As her college career progressed, Todd expanded her knowledge base and her professional network through three important internships: as a member of the IndyCar accident investigation and tech inspection team; as a data engineering intern at Juncos Racing; and finally, as an engineering intern at Team Penske’s North Carolina headquarters.

“Our students get tired of hearing this from all our guest speakers: it’s networking, networking, networking. That’s how you get into motorsports,” Talbert-Hatch says.

Todd took that advice to heart, staying in touch with many established veterans who helped her build a career in the racing circuit she grew up following.

Career progress

Todd accepted the Penske internship in hopes that she might parlay it into a full-time job after graduation. While that didn’t pan out, her experience there did help her land a gig as a systems engineer at Andretti Autosport before she had even graduated from college.

She spent three seasons working on the No. 28 car driven by Ryan Hunter-Reay — incidentally, the winning driver in 2014, the only Indy 500 Todd has missed since attending the race for the first time — before accepting an opportunity to work at Arrow McLaren alongside another mentor, Kate Gundlach, whom she has admired since they met during Todd’s IndyCar internship.

“She was working at Ganassi at the time and came over and introduced herself and was like, ‘Whatever you need internship-wise, if you need any help, if you just want to go get dinner and ask me questions, I’m here for it. I’m here for you,’” Todd recalls. “To have that kind of mentorship right off the bat was incredible. And so I stayed in contact with her while I was in college, and she was super excited for me when I got my job at Andretti, and I always liked the idea of working with her.”

The opportunity arose during the 2022 season, when a systems engineer left the Arrow McLaren team where Gundlach worked. Todd accepted an offer to discuss the position with team leadership, recognized growth opportunities and was happy to have a chance to work alongside several friends she’d made during her first few years in the paddock.

For two seasons, she worked under performance engineer Gundlach (now Arrow McLaren driver Nolan Siegel’s race engineer) and race engineer Will Anderson on the No. 5 Arrow McLaren Chevrolet driven by Pato O’Ward, in a role with more responsibilities than the one she held at Andretti.

“I’m still responsible for all the electronics, radios, telemetry in the car, but I calculate fuel mileage now, which is a role that is done by the performance engineers at Andretti,” Todd says. “Now I have a much bigger responsibility car-side in practice, qualifying and, of course, the race because that is all strategy. So I work very closely with the strategist, and I definitely feel like I have a voice and an active role in the outcome of how we finish every race weekend.”

Another aspect of working for Arrow McLaren that initially appealed to Todd was its organizational reputation for creative thinking, for hiring from within and for providing practical opportunities to develop new skills.

Todd has already benefited from such an opportunity when she got to try her hand as a performance engineer — a position she hopes to occupy as her career progresses — during an offseason testing session.

She has made it so far so fast that Todd admits it can be frustrating to wait for that promotion to come. When those frustrations arise, she has the luxury of leaning on strong mentors who understand how hard the business can be and often have been in the very same position. They help her maintain a healthy perspective, knowing that if she keeps working hard and learning, more opportunities to advance will naturally arise.

“I have this specific idea of what I want. I know I want to be a performance engineer. I want to be a race engineer. I want to go into upper management,” Todd said during the 2024 season. “But timeline-wise, I want it to happen naturally. This is my fifth season as a systems engineer, which can be frustrating, but it has been really cool to kind of realize how far I’ve come and how much I’ve learned over the last five years. I know generally where I want to go and what it takes to get there, but I’m not going to put deadlines on myself and then be disappointed by it.

“I really want to be put in a position where I’m given a promotion because the people around me think I’m ready for it, and they know I’m going to succeed in that position.”

Spoken like an engineer who listened to mentors’ valuable guidance along the way.

Our students get tired of hearing this from all our guest speakers: it’s networking, networking, networking. That’s how you get into motorsports.

Terri Talbert Hatch,

co-founder of the motorsports engineering program

From baby brother to Boilermaker All-American

Dillon Thieneman is walking to class. The students lugging backpacks as they trudge past Jimmy John’s, Von’s and Harry’s don’t seem to notice an All-American is in their midst.

Thieneman carries his backpack strapped over both shoulders. His destination is Rawls Hall for Management 254, the Legal Foundations of Business class. It’s a chilly Wednesday, but Thieneman isn’t dressed for it. He has no coat, just a white T-shirt and black pants.

“Have to take care of the books,” he says.

In the spring of 2023, Thieneman was trying to find his place amid the hustle and bustle of Purdue’s red-brick campus. He had arrived early from his Indianapolis-area home, wanting to get a jump on his football career.

It worked.

He’s a freshly minted All-American, coming off arguably the best true freshman season in school annals. Thieneman is already a BMOC (Big Man On Campus). So much, so fast. How did he arrive at this moment?

The brothers knew

If anyone was listening, former Boilermaker Jake Thieneman was telling us about his youngest brother.

“We all knew it a long time ago,” fessed Jake.

The oldest of the three Thieneman brothers, Jake became convinced of Dillon’s prowess when his kid brother played grade school flag football for Saint Maria Goretti in Westfield, Ind. Here’s where Brennan Thieneman, the middle brother, picks up the story …

“Dillon took the ball and juked eight players, every guy on the field,” he said. “Jake and I were refereeing, and we high-fived each other. It was unbelievable. I had never seen anything like it. They used to limit how much Dillon could carry the ball because he’d have three carries, three touchdowns.”

It just wasn’t fair.

“It was absurd,” said Jake. “He was always the most athletic kid at whatever he did.”

Jake and Brennan—who each played safety at Purdue, too—have had a front-row seat for the development of the “little Dillon.” They are eight (Jake, 1996) and seven (Brennan, 1997) years older than Dillon (2004), often de facto parents.

Now, the rest of the nation knows: Dillon Thieneman is good. Very good. All-American good. The final stat sheet from 2023 says he led the nation’s freshmen in tackles, interceptions and forced fumbles.

The All-American honors poured in …

- The Football Writers Association of America

- The Athletic

- 247

- FWAA Defensive Freshman Player of the Year

- Big Ten Freshman of the Year

Dillon shrugs his shoulders. He’s unphased. It’s as if he expected it. You could say that, to a degree, he did. He’s been on this path since middle school when Jake typed out a workout program at Dillon’s request. He just wanted to keep up.

“Brennan and I were going to give him the answers to the test,” said Jake. “We were going to take everything we learned and just pass it on to Dillon to get him started earlier.”

Agility work, position-specific drills, speed training … Jake and Brennan devised a comprehensive plan.

“He was doing ladders,” said Jake. “He was doing different footwork stuff. He was doing bodyweight stuff. And he was doing his defensive back drills.”

Dillon also did daily push-ups and pull-ups. This single-minded focus left Brennan and Jake shaking their heads.

“He was always very diligent even though he was younger and kids his age weren’t doing that stuff,” said Brennan.

Soon, Thieneman found himself starting as a freshman at Westfield High. Schools wanted him. Northwestern sniffed around. And so did Duke and Minnesota, which really wanted him. But Thieneman was in the bag for Purdue all along, really. He committed on June 14, 2022, before his season season.

“Most felt I was going to go to Purdue, so they backed off,” said Dillon.

Thieneman was a Boilermaker, just like his brothers and father, Ken. His mom, Shannon? She went to Indiana.

“But she’s converted,” said Dillon, smiling.

Banner day

Dillon Thieneman is the kid next door who cuts your lawn, shovels your driveway and bags your groceries. He is also really good at football. How good? He received the ultimate Purdue honor on the first day of spring ball following his freshman year when an All-American banner bearing his image was unfurled in the Mollenkopf Athletic Center.

“I knew he was going to come in and ball out,” said Brennan. “I had no doubt about that. But at an All-American level? I don’t know if I had expectations there. I’d say that that did exceed my already high expectations.”

There’s Dillon, up on the wall with Boilermaker luminaries like Rod Woodson, Drew Brees, Mark Herrmann and Ryan Kerrigan.

“(My teammates) are the real reason that I was able to play to get up there,” said Thieneman.

There’s that maturity. He’s 20 going on 35. And his work ethic? It’s described like this: He combines a walk-on mentality with an All-American’s ability.

“It’s like he was created in a lab somewhere,” Ryan Walters said. “You try to find things in his game, his personality, things in his life where you’re like, ‘Oh, he needs to pick it up in this area.’ We get the (academic) grade report; his lowest grade right now is 99.

“Have I coached anybody like him before? No, I haven’t. Not at (his age). Not as talented as he is. Not with the work ethic and the hunger that he has. If I were a betting man, I would say he’s got a long time to play football.”

Purdue safeties coach Grant O’Brien shakes his head at his gift from the football gods. He knows he’s lucky.

“He’s got a mental skill set to do something special because of how he approaches a simple task,” said O’Brien. “Last spring, I was like, ‘this guy might have something special,’ and then it obviously translated to production on the field.”

How did this happen? How did Dillon Thieneman—who turned 20 in August—get here so quickly? And what’s next for a player who, as just a sophomore, already is the face of Purdue Football?

Learning the hard way

Throw me the ball! Throw me the ball!

Dillon Thieneman could be a pest as a kid. You know how little brothers can be.

“He always has been extremely competitive,” said Dillon’s mom, Shannon Thieneman. “He wanted Ken and Jake and Brennan to throw him the football or basketball or whatever it is … just keep throwing it to him.”

So, they would throw it as hard as they could at him.

“And he didn’t always catch it as a little kid and then it would hit him in the face,” said Shannon. “So, he learned the hard way.”

Brennan often paid for it: “He’d cry to mom, and I’d get in trouble.”

Through that veil of tears, Dillon got tough. And better.

“He’d want Brennan and I to throw him into the couch harder and harder,” said Jake. “It usually ended up with Dillon crying. But he asked for it.

“But that was just Dillon.”

Brennan was especially hard on Dillon during a game they invented called “The Return Game.” It was pretty simple: Brennan would boot the ball to Dillon, who would earn points based on how far he ran back the ball. It often wasn’t too far, with Brennan having no mercy on his young brother.

“They played a lot of games together,” said Shannon. “But he didn’t let (Brennan) get away with anything because he was the younger brother. He was tough on him.”

Jake and Brennan quickly saw what the rest of the Purdue fans saw last fall: Dillon Thieneman is more athletic than you think.

Ask anyone on the Purdue team and they’ll tell you. Thieneman is a legit blazer, one of the two or three fastest players. The only one on defense on par is defensive back Kyndrich Breedlove. On offense, wide receiver CJ Smith is all gas. But Thieneman is right there, fast … and fearless.

“At four years old, we teach them how to do a front flip,” said Jake. “So, he nails the front flip off the diving board the first time. Brennan and I don’t say a single word as he gets out of the pool, goes back on the diving board and immediately does a backflip. We didn’t tell him anything. He’d just been watching us that entire time.”

Dillon was always watching, observing, listening and tagging along. He wanted to be like Jake and Brennan. He watched each star at Guerin Catholic High in Noblesville. Dillon saw their work ethic, their drive and motivation, which propelled both Jake and Brennan to Purdue as walk-ons who developed into key contributors and scholarship players for the program in the Jeff Brohm era.

“He started seeing Brennan and I play, which pushed him to go even harder,” said Jake. “It’s like he’s been training hard on his own since seventh grade.

That work ethic and supreme athletic ability launched Thieneman to a stellar career at Westfield High, and on to Purdue.

“I kind of knew from the spring what he was,” said fellow safety Sanoussi Kane, a senior on last year’s team. “It’s awesome to see all this hard work pay off. He’s one of the hardest workers on the team, if not the hardest.”

Knowing what he wants

Want to see Dillon Thieneman smile? Put a plate of pasta in front of him.

“Homemade sauce, chicken, that’s what he always asked me to make,” said Shannon. “That’s his favorite, and he likes to help me. He’s not a junk food eater. It’s all part of the training.”

Shannon would prepare a pasta bar for her children, including sister, Kiera.

“I loved it,” said Dillon.

Thieneman has always known what he wanted. He played basketball, and he was a pretty good baseball player. But football was his fixation and sole focus in high school. He knew. He knew he could be special. Mom and Dad knew, too. They had a transformative talk with Dillon before he entered high school.

“We told him he had to put in the work now, not wait until you get to college or get into high school,” said Shannon. “You have to be prepared by the time you get into high school. That’s why he was able to start at a 6A program as a freshman; he was willing to put in the work.

“He’s doing what we always knew he could do. He did it as a freshman. And I don’t think we were expecting him to be an All-American as a freshman. We knew he would be at some point, but that was a wonderful surprise.”

Thieneman now finds himself as a respected leader on the 2024 Boilermakers, trying to set the tone for a program in Year Two under Walters. The goal: flip the script on last year’s 4-8 season.

He’s grown into a 6-0, 205-pound all-muscle man. Thieneman cinches a headband around his noggin after pulling on his No. 31 jersey. He surveys the field from a perch high above the defense, setting up roughly 20 yards from the line of scrimmage, almost seemingly out of place.

Is it too deep? Nope.

From that distance, Thieneman is asked to scan the field. In football parlance, he can play “downhill,” breaking on plays quickly, reading schemes, moving at top speed and attacking.

He announced his presence in the season opener vs. Fresno State when he picked off one of his freshman-record six passes on the year. It was a beaut. But he delivered a hit in punt coverage—leveling a Bulldog—that resonated and perhaps personified what Thieneman is all about, doing blue-collar work usually reserved for walk-ons.

“He loves being on punt coverage,” said Purdue special teams coach Chris Petrilli. “He never wanted to come off.”

And he probably won’t. Thieneman may even end up running back punts this season.

“I knew he was going to be a special player just based on how he carries himself, his character, his work ethic, what he pours into his craft every single day on and off the field,” said O’Brien. “You never envision exactly where a young man will be at his freshman year or even his career as far as being an All-American. But I think it’s just a testimony to what he’s about from a character standpoint.

“People have mentored him; his work has just spoken for itself. That established him as a starter after the spring when he first came in. It continued through the summer and (he) had a phenomenal year as a true freshman.”

Academic expectations

Jake Thieneman majored in engineering. So did Brennan and father, Ken, who owns Thieneman Construction. Smarts run in the Thieneman family. It’s not all about PBUs, INTs and TFLs.

“Our parents put a huge emphasis on academics,” said Jake. “It came before anything else – sports, training, playing outside. The biggest thing my parents did was instill in us very high standards for ourselves. A’s were expected.”

Achievement was celebrated in the Thieneman house. Kitchen cabinets were adorned with tests that earned an “A.” Report cards that glistened with good marks were also on display as the kids ate their cereal and Pop-Tarts in the mornings.

“It became a competition with Brennan and me to hang as much as possible,” said Jake. “We completely covered the kitchen.”

Of course, Dillon had to keep up. And he did. His goal at Purdue is to graduate as soon as he can. He enrolled a semester early and was in the School of Engineering for the first two semesters before switching to management.

“I did feel some pressure, but in the end everyone wanted me to do and study something that I wanted to do, so I got tons of support when I was considering and making the change,” said Dillon.

Thieneman’s schedule was loaded with five classes during the 2024 spring semester: MGMT 254, MGMT 200, ECON 251, ECON 252, EAPS 106 … He piled more on, taking a course in May and two more over the summer in advance of his sophomore season.

“Academics were always a heavy emphasis for our family,” said Brennan. “My dad, being involved in managing construction, told us from a young age, ‘You can spend the rest of your life working with your back, or you can study hard, go to college, and work with your brain.’ So, good grades were not only significant to my parents but were also incentivized.”

Peer review

Cam Allen smiles as he considers the question: What makes Dillon Thieneman good?

“My man Dillon, coming in, in the weight room, on the field, however you look at it, he’s already on top of the boards in everything,” said Allen. “Looking through my eyes, there’s a lot of things he does that I (haven’t) seen a true freshman do in a long time.”

Players four and five years older than Thieneman took cues from the new kid, the youngster inspiring oldsters.

“I would say just the level of his preparation,” fessed defensive lineman Isaiah Nichols when asked what makes the precocious Thieneman special.

“He’s a lot more mature than his age and his experience. We’re in the hotel, and I come off the elevator before the game, and I see him going over his tip sheets and everything.”

Remember: Jake Thieneman was trying to tell us how good his kid brother was. What’s next?

The secondary must replace Allen and Kane. The search is on for two new tackles. And who will rush the passer with Nic Scourton having transferred and Kydran Jenkins now playing linebacker?

“I’m still working toward (being a leader),” said Thieneman. “It’s a new thing. But I think people think of me as a leader, and I’ve got to step up into that leadership role.”

Thieneman will grow into a leadership role vocally. He’s already leading by example. He’s the first guy at practice, and he always lingers afterward doing extra work, fine-tuning his breaks, back-pedaling… always looking for an edge amid his nuanced work. It has commanded the respect of peers.

“It’s really still the beginning for him,” said O’Brien. “It’s about where he can take his game next.”

By Tom Dienhart, who has covered Purdue football for GoldandBlack.com since 2019. He earned a B.A. Communications degree from Purdue in 1987.

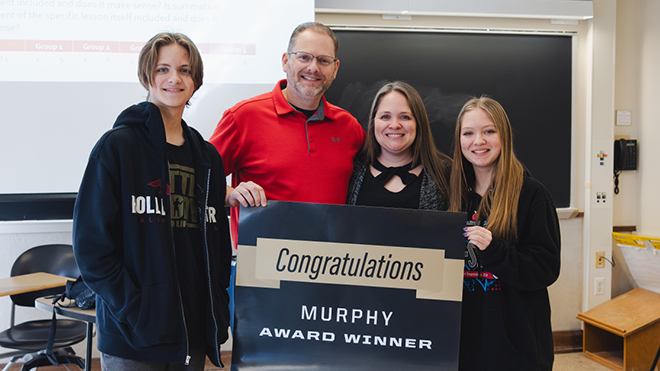

2024 Charles B. Murphy Award winners represent five Purdue colleges

The university’s highest undergraduate teaching honor recognizes accomplished educators across campus

This year’s recipients of Purdue’s highest undergraduate teaching honor have not only bettered Boilermakers’ educations but have influenced today’s teaching environment and tomorrow’s workforce. They’re shaping the future from their classrooms. Meet the 2024 Charles B. Murphy Award winners:

Kendra Erk

How do Purdue engineering students learn best? Associate professor Kendra Erk knows from her own experience — she earned her bachelor’s degree from the university. She joined the faculty in 2012 and began leading Boilermakers in materials engineering (MSE).

As an instigator of improvements, Erk has positively impacted Purdue students, as well as the future of education across the state. In addition to ensuring students receive a world-class education in the classroom and research lab, as well as leading the MSE Safety Committee, she has also collaborated with the engineering department at Ivy Tech Lafayette to enrich its curriculum. She has promoted engineering education through her work as a developer and coprincipal investigator on Project UPDATE, a program funded by the National Science Foundation that integrates engineering design principles into soon-to-be teachers’ science lesson plans.

Every day, Erk prioritizes three themes, whether she is instructing students, developing plans or pursuing goals: Be respectful, resourceful and resilient. With the confidence and credibility brought by the Charles B. Murphy Award, she can pursue even more of her ideas. “It provides a platform to make our curriculum better,” she says. “It means so much to me as an educator that this award will help us improve what our faculty delivers and what our students gain.”

Dino Felluga

Professor Dino Felluga leads English courses, study abroad programs and research projects, adhering to a principle from Leonardo da Vinci: “Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Being willing is not enough; we must do.” His students engage in hands-on lessons that leave them with widened perspectives and deepened understanding.

While instilling curiosity in others, Felluga has invented his own resources and revised classes. His active-learning assignments encourage students’ creativity, from recreating “Citizen Kane” scenes for a film class to presenting on the streets of Italy during a study abroad trip. When he is unable to find the right tools, he builds them himself, including the online resources Introductory Guide to Critical Theory; Britain, Representation, and Nineteenth-Century History; and Collaborative Organization for Virtual Education. He has also written “Critical Theory: The Key Concepts,” “The Encyclopedia of Victorian Literature,” “The Perversity of Poetry” and “Novel-Poetry,” set to be published in September 2024 by Oxford University Press.

“Novel-Poetry” was cowritten with Emily Allen, Felluga’s wife. Allen is an associate professor of English and founding director of the John Martinson Honors College’s Blue Sky Teaching and Learning Laboratory — as well as a 2002 Charles B. Murphy Award winner. “We’re the only couple to both receive the Murphy in the history of the award,” he says. “Purdue’s been supportive of our efforts, and the Honors College has allowed both of us to really engage with the rest of the university.”

Stephanie Gardner

Approaching teaching and mentoring from a student-centered perspective is essential to supporting Boilermakers in the classroom and beyond — like in research laboratories, which make a biology student’s undergraduate experience more meaningful. “It’s so important to their education,” says associate professor Stephanie Gardner. “Research is where they strengthen interpersonal skills, spark up interests and learn how new knowledge forms.”

Since arriving at Purdue as a lecturer in 2007, Gardner has prioritized evidence-based instructional practices and equitable access to research. She has provided for students on campus by developing Course-based Undergraduate Research Experiences, funded by the National Science Foundation, and training instructors as part of the program. As a coprincipal investigator of Partnering in Research Mentoring for Minoritized Students in STEM, she has helped mentors and mentees at Purdue and Chicago State University. In 2024, she was selected to become a fellow of the Partnership for Undergraduate Life Science Education, a national program that aims to support departments and instructors in improving undergraduate learning of life sciences and other related disciplines.

Serving students not only at the university but across the country is always Gardner’s goal, and the Charles B. Murphy Award is a message to keep going above and beyond. “What drives me is helping students feel like they belong,” she says. “I want them to feel valued and like they have the capacity to master anything they’re trying to learn.”

I want them to feel valued and like they have the capacity to master anything they’re trying to learn.

Stephanie Gardner

Associate professor of biological sciences

Amy Sheehan

What do pharmacists need to know? Understanding medical literature, thinking critically about research, and communicating with peers, physicians and patients are only a few of the role’s many responsibilities. Professor Amy Sheehan prepares Boilermakers for their careers by continuously providing real-world practice.

Sheehan has introduced practical activities, revised review processes and integrated new technologies since joining the Purdue faculty in 1998. The developments of a mock drug question assignment and a drug formulary monograph, which integrate examples from her own work at Indiana University Health’s drug information center, have taught students how to effectively respond to drug-related questions and patient-specific situations. She has also incorporated constructive peer reviews and encouraged student-to-student mentorship to start building networks.

Working with the Innovative Learning hub, Sheehan is implementing artificial intelligence into the peer-review system while educating students on ethical AI usage. “I’m really excited for its impact on teaching and learning,” she says. The Charles B. Murphy Award is a motivator to keep going. “I want to continue to offer the best learning experience for my students.”

Jennifer Smith

When clinical associate professor Jennifer Smith finished her first day of student teaching, she called her mom and said she knew it was what she wanted to do for the rest of her life. Fifteen years of working in elementary schools and almost five years of educating at Purdue have only brightened that innate spark.

In the College of Education, Smith has illuminated ways for future teachers to connect with students. Focusing on special education curriculums, she has prepared Boilermakers for excellence by improving courses, researching teacher-student dynamics and cofounding the Center for Research and Equipment for Assistive Technology in Education (CREATE) and the Accessible Creative Teaching and Inclusive Opportunities Now! Research Lab. Her involvement in national conferences helps her share ideas across the United States.

CREATE empowers the next generation of learners with accessible resources like software and equipment. Since its establishment, the center has inspired students to create practical solutions. The Charles B. Murphy Award is a recognition for her accomplishments — and encouragement to keep building. “Innovation is one of Purdue’s values, and students are representing that at CREATE,” Smith says. “Now we’re looking into how we can expand and capitalize on all of the amazing progress.”

Excellence in Instruction Award winner for 2024 announced

Linda Haynes has served students with care and innovative solutions for over 30 years

Linda Haynes, a senior lecturer and associate director of introductory composition in the College of Liberal Arts, considers teaching her students to find reliable sources to be one of the most important things she does. It’s during those lessons that she experiences one of her favorite educational moments, when she senses a shift in the energy of the classroom as evidenced by a particular, surprising sound.

Silence.

“There’s something about that quiet, that intense work they’re doing. You can almost hear their brains working, those synapses firing,” she says. “When they get like that, I know I’ve hit something, they’re really understanding what it is to enjoy the treasure hunt of research.”

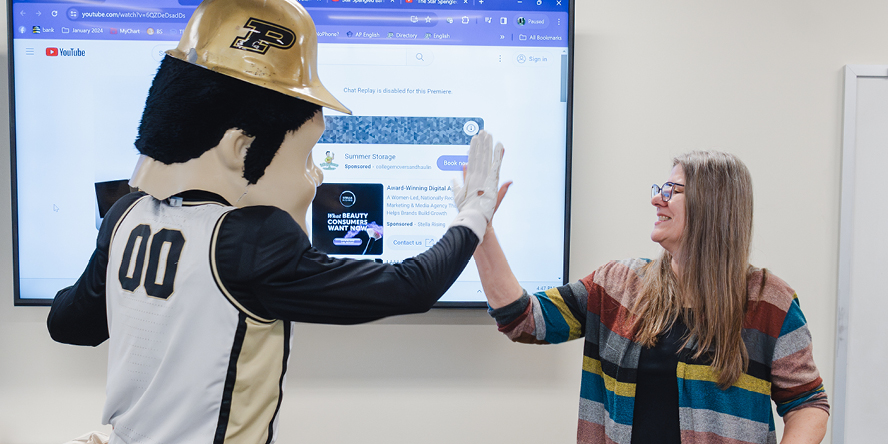

It’s this devotion to her students’ learning that earned her the prestigious 2024 Excellence in Instruction Award. This award is presented annually to a lecturer or senior lecturer who has gone above and beyond for their students during their years of service to the university. Haynes received a surprise presentation in her classroom by Purdue Pete, family and colleagues.

Since she began her teaching and advising career at Purdue in 1993, Haynes has played a pivotal role in advancing the university’s educational mission by delivering innovative, high-quality writing instruction to thousands of undergraduate students, both in her instructional role and her administrative role as assistant director, and now associate director, of the Introductory Composition at Purdue (ICaP) program. She’s taught 16 different courses for the Department of English, seven of which she helped to design or redesign. Since 2004, she’s offered hands-on writing instruction to over 1,200 undergraduate students in 56 separate sections.

Haynes — known for her devotion to setting up students for success, as well as her innovative approach — put both on display at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. She was conducting an early pilot of Purdue’s new learning management system, Brightspace, with a mentor group of graduate students when learning abruptly shifted to an online model, making the pilot more urgent. Over the summer of 2020, Haynes trained directly with D2L, the developer of Brightspace, to understand the software so that she could then introduce and translate the information to all ICaP writing instructors.

Despite tremendous accomplishments throughout her decades of service, Haynes is unassuming. “I have no expectations for winning anything like this,” she says of the award. “But when 20-30 people suddenly burst into your classroom with photographers and balloons and Purdue Pete, it really brings out the community aspect of the job. You realize you don’t simply teach your class and go home. It has lasting effects.”

There’s something about that quiet, that intense work they’re doing. … When they get like that, I know I’ve hit something.

Linda Haynes

Senior lecturer and associate director of introductory composition

College of Liberal Arts

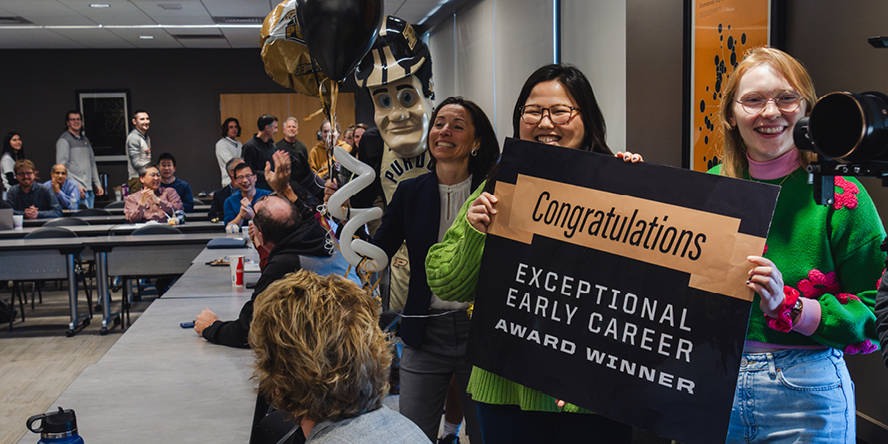

Exceptional Early Career Teaching Award honors two undergraduate faculty

Betsy Parkinson and Lindsey Payne recognized for excellence in and out of the classroom

Betsy Parkinson and Lindsey Payne, winners of the 2023-24 Exceptional Early Career Teaching Award, embody the ideal that the “teaching responsibility to students does not stop at the classroom door.” They persistently demonstrate their “readiness to aid and motivate students in a counseling and advisory capacity” through distinctive strategies and simple acts of kindness.

Purdue University began offering the early career award to honor outstanding undergraduate faculty members on the West Lafayette campus with the rank of assistant professor. Of the hundreds of Boilermakers eligible, Parkinson and Payne have distinguished themselves not only as skilled educators, but also as remarkable human beings.

I am so appreciative of my students. There are many fantastic professors on Purdue’s campus, and it’s just a huge honor to receive this award.

Betsy Parkinson

Assistant professor of chemistry and medicinal chemistry and molecular pharmacology

Betsy Parkinson

Betsy Parkinson, assistant professor of chemistry and medicinal chemistry and molecular pharmacology, fell in love with both science and teaching at an early age. Her experiences growing up on a farm in Mississippi inspired, in part, her current research on soil-dwelling bacteria and medicines based on natural products (molecules made by living organisms). Her passion for sharing knowledge is something that has always been a part of her, too.

“I’ve loved teaching for a long time,” she says. “Even in middle school, I was the annoying kid who was trying to tutor her friends. I was like, ‘I can tutor you. I can tutor you.’ Being honored with the Early Career award for doing something that I love is so special to me. I really appreciate it.”

Parkinson’s path to Purdue started with her undergraduate education at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee, where she majored in chemistry and participated in undergraduate research at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

“I was in a molecular pharmacology lab at St. Jude,” she explains. “So early on, I was at the interface between biology and chemistry.”

Parkinson’s research interests grew, and in graduate school she explored nature-made medicines at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Parkinson started at Purdue in 2018 and since then has taught organic chemistry to more than 2,000 undergraduates. She takes the pulse of her students on day one of classes.

“I give students a survey about their feelings toward organic chemistry,” she explains. “Right off the bat I acknowledge they might be scared or nervous. But I reassure them that, although we cover a lot of content, if they study 30 minutes a day, they will be fine. They may not get an A, but they will be totally fine.”

Parkinson has implemented other strategies too, like “Friday Fun Lectures,” which help students connect organic chemistry concepts to their other academic interests, and “Chill With a Chemist” meetings with students outside of class. Supporting struggling students with extra help sessions and promoting on-campus mental health resources are just a few of the ways Parkinson is making a difference in the lives of her students.

“I am so appreciative of my students,” Parkinson says. “There are many fantastic professors on Purdue’s campus, and it’s just a huge honor to receive this award.”

Having the Early Career award be student-centered makes it especially meaningful for me. Knowing that those I am directly impacting are advocating for me reinforces that what I am doing is working. And I really appreciate that.

Lindsey Payne

Director of service-learning and

assistant professor of practice in environmental and ecological engineering

Lindsey Payne

Lindsey Payne has been the director of service-learning for Purdue’s Office of Engagement since 2015 and assistant professor of practice in environmental and ecological engineering since 2021. Her teaching experience began long before that, though.

“I taught high school for four years,” she says. “Biology, earth science and even PE.” Payne also worked for a variety of nonprofits as an educator.

When one of Payne’s colleagues recommended she consider Purdue’s PhD program in ecological sciences and engineering, her career in education moved in a new direction.

As a graduate student at Purdue, Payne worked in the teaching and learning center, and when Larry Nies was looking for a teaching assistant for an environmental and ecological engineering class, her name came up. Payne worked with him in that role for four years, advancing to co-instructor of the class and eventually assisting with redesigning the course.

Nies also gave Payne the opportunity to develop her own service-learning course and to serve as the instructor of record. “And I realized at that point that I truly loved teaching at the college level,” she says.

Payne currently teaches an introductory environmental and ecological engineering class for second-year students, an upper-level service-learning course and an experiential education course for seniors.

“My focus is not just on getting students to become impressive practicing professionals,” she says, “but also on getting them to engage in their communities, to do more than just go to work.”

Payne’s longstanding partnership with the Wabash River Enhancement Corporation enables her students to make community connections with underserved populations and local nonprofits. Students gain professional engineering experience — design, communication, teamwork, grant writing, budget management and leadership — as they oversee a project from inception to implementation.

“They support the implementation of rain gardens and native plantings to capture stormwater on various community partner properties,” she says. “All with the goal of increasing the health of the Wabash River.”

The health of her students is equally important to Payne, and she has mental wellness check-ins with them every other week via Brightspace. She says that in final course evaluations, students express how much they appreciate her concern for them.

“Having the Early Career award be student-centered makes it especially meaningful for me,” she says. “Knowing that those I am directly impacting are advocating for me reinforces that what I am doing is working. And I really appreciate that.”

Made for more: Purdue Global Law School grad saw a future after football

Tony Jackson earned his Executive Juris Doctor degree online, and it’s empowering his entrepreneurial journey

Millions of young men across the United States might say a professional football career is the ultimate dream. And after a successful college career at the University of Iowa, Tony Jackson (Executive Juris Doctor ’21, Purdue Global Law School) did earn himself a spot with the Seattle Seahawks in 2005 as a sixth-round draft pick.

But he always knew he was made for more.

In his life after pro football, he’s still adding achievements to the trophy case, and these post-athletic accomplishments mean even more to him. He’s created and run multiple successful companies, launched several passion projects and earned a law degree with Purdue Global Law School while running a business and starting a family.

Jackson was an entrepreneur before he decided to go back to school for an advanced degree, but he says his executive juris doctor exponentially evolved his business and his abilities as a professional — fast.

And yet, Jackson is remarkably humble about it all.

“If I had to brag, one thing I’m very good at is surrounding myself with people who are better and smarter than me, and I learn from them,” he says. “One of my favorite quotes is by Sir Isaac Newton: ‘If I’ve seen further, it’s because I’ve stood on the shoulders of giants.’”

The giants in Jackson’s life lifted him up so he could see the possibility of a future of his own making. In fact, Jackson’s story is less about football than it is about the men who taught him. Now he’s paying it forward.

The power of a chosen family

Their names were Sandy Sanders and Rufus Pipkins.

“It wasn’t exactly the mean streets of downtown Detroit, but socioeconomically, there were some challenges,” Jackson says of his hometown. “I didn’t know many men growing up — especially Black men — who had graduated from college.”

That’s why Sanders (one of his elementary school teachers and the father of two of his good friends) and Pipkins (his high school football coach) had such a tremendous impact on him. Sanders, who had a master’s degree in education, served as a father figure for many years.

When Jackson was in high school and starting to get some publicity as a football standout, Sanders was still checking on him. But he was less concerned with his athletic plans and stressed academic pursuits. Sanders regularly riddled him with questions. What was Jackson’s GPA? What classes was he taking? Was it the right load? Are they the right ones to prepare him for the academic rigor of college?

And Pipkins, who had an engineering degree, was there at one of the most crucial moments of Jackson’s life. He took Jackson into his home when he lost his mom during his senior year. And in addition to the support a teenager needs from a loving adult, living with Pipkins also gave Jackson an insider’s look into the life and career of an engineer.

Those men, Jackson says, shaped his outlook of academics over athletics — which ultimately ensured his success in both. After finishing his college football career strongly, he graduated from the University of Iowa with a BS in economics and a minor in business.

“My relationship with these two men gave me the confidence that not only was I going to attend college, I was going to succeed and graduate,” he says. “Many college athletes don’t make it past their freshman year because they aren’t prepared to be independent and academically successful. But I felt prepared.”

An off-the-field comeback

When he left the NFL, Jackson was often asked, “Don’t you miss playing?” While it felt like the answer should have been yes — it was an experience of a lifetime — he didn’t, at all. It made him realize it wasn’t really the sport itself that he loved. It was, perhaps, its parts.

“Football was my ticket to education. It allowed me to change my environment and create my own future. But I’m not sure how much I liked the game. It was the team aspect of it that was impactful to me,” he says.

He also was discovering that corporate life was definitely not for him. The atmosphere, after spending most of his adolescence profoundly united with his teammates, felt disconnected.

“Having a co-worker and having a teammate are completely different things,” he says. “I was used to having teammates who were like brothers. You’d do anything for each other.”

So Jackson and his wife, surgeon and dermatologist Dr. Mercy Odueyungbo, opened their own dermatology practice.

Jackson says that getting out of corporate life felt like the complete answer he’d been looking for. It was everything he loved about football, without being football.

“The thing I loved most about playing was the teamwork,” he says. “As an entrepreneur, you can set the vision. Everybody’s working together, and it makes the day fun. You’re competing. You keep a scoreboard; you have an objective. It’s not simply getting up and ‘making the doughnuts’ every day and not seeing or feeling passionate about what you’re working toward.”

But soon, he sensed they were at a crossroads.

“I started to feel a bit stagnant,” he says. “I wanted to do something bigger, something more. I wasn’t quite sure what that thing was, but I was certain it had to come about by additional education.”

But it wasn’t an MBA he went back for.

“I never intended to be a lawyer. But learning the law is learning the rule book of business,” he says. “The executive juris doctor I got from Purdue Global is what made me an executive.”

The executive juris doctor I got from Purdue Global is what made me an executive.

Tony Jackson

Executive Juris Doctor ’21, Purdue Global Law School

Moving toward a passion

With a degree in economics and business, Jackson was used to information being presented conceptually, and he didn’t feel like it had much practical application — at least not in any way that interested him.

But Purdue Global Law School was different.

“I started law school right when we were working to expand our company. We were going from a small, niche market — five or six people — to tripling in size,” he says. “I suddenly had HR duties; I had to know employment law; there were contracts being negotiated and signed. I was learning those things at Purdue Global at night, and then I’d actually do it during the day.”

Now, as an alumnus, life is different.

First, he’s a dad, which is the greatest joy of his life.

“As a person who grew up without a father, being a dad was always something I wanted to excel at. It’s almost like the competitive mentality I had with sports,” he says. “Being a dad is a badge of honor for me.”

Serving as a role model for his daughters is a lifelong dream come true, but he wants more role models, more inspirational humans, more visible giants for everyone’s kids. He knew he could have an impact in media by holding up one example after another.

“Typically, what we see is the entertainers — musicians, athletes, performers. They’ve ended up being the spokespeople for African Americans, but they don’t represent the true demographic. There are far more Black doctors than there are Black NBA players; there are more Black accountants, lawyers, engineers, writers and other professionals. That’s why we create content that shows African Americans in a different, more accurate light than what’s commonly portrayed.”

It was to fill this need that he founded Jackson Media Group, which operates several media properties he also owns. Its first project was a reality television series featuring his wife that aired on TLC. “Dr. Mercy” told the day-to-day stories of treating patients in their dermatology practice. Jackson says there was an immediate, positive outpouring.

“Seeing a Black, female doctor on TV impacted a lot of people. Little girls were dressing up as her for Halloween! It meant something, to kids especially, to see that it’s clear she’s a normal person. She’s not normal — she’s exceptional — but she’s showing little girls that you can be a Black woman and achieve what she has without having to be on a stage,” he says.

So he comes full circle, back to his childhood and the giants who offered their shoulders to stand on. And he thinks about the profound impact a single visible role model can have for Black children who might not otherwise see the possibilities.

“For our kids, our ceiling is their floor,” he says. “Wherever we stop off, that’s their beginning.”

For our kids, our ceiling is their floor. Wherever we stop off, that’s their beginning.

Tony Jackson

Executive Juris Doctor ’21

Purdue Global Law School

Innovative major draws student to Purdue University in Indianapolis

Strong industry connections and hands-on learning set Carys George up for success in themed entertainment design.

Industry internships, flexible class schedules and supportive professors are just a few of the things that Carys George, a Purdue themed entertainment design student in Indianapolis, loves about her major. Riding roller coasters as part of her education? That’s just a bonus.

An internship like no other

Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, opened in the late 1800s and is considered the second-oldest operating amusement park in the U.S. It’s home to 68 rides, including 18 world-class roller coasters. George has ridden them all.

“Last summer, I was a ride audit intern at Cedar Point working in the operations office,” she says. “There were just two auditing interns, so we were pretty busy.”

What exactly is a ride audit? It’s one of Cedar Point’s methods of making sure that rules and safety procedures are being followed. Every park in the Cedar Fair chain, which owns Cedar Point, is certified under a specific operations protocol. It was George’s job to help ensure the system was being followed.

“Checking seat belts, checking lap bars, announcing the rules to guests, it’s all part of it,” she says. “If employees don’t do it correctly every time, it’s ‘not compliant’ or ‘minimal compliance,’ and I would mark that down on the audit.”

Ride audits happen in two ways: in uniform and undercover.

I love the combination of technology with leadership, operations and creativity. It all comes together in themed entertainment.

Carys George Purdue themed entertainment design student in Indianapolis

“When you audit in uniform, it’s very obvious to everyone why you are there,” she explains. “For undercover audits, you dress up as a guest. Sunglasses. Wigs. Outfits. I had a drawer full of props that I would use. Sometimes we even had spy glasses with a camera in them.”

George’s duties in this role varied. Some days she would ride attractions as a guest and make note of any violations. At other times she used a fake pass, or even no pass, in the Fast Lane to see how employees would handle it. She also monitored alternate queues and elevators for guests who could not wait in line or needed assistance accessing a ride.

And, of course, riding all the attractions multiple times is how George collected that data. She admits to “not loving” auditing the spinning rides, but she does have a favorite coaster.

“My favorite ride has always been the Magnum XL 200. It’s a coaster from 1989, the first-ever coaster to top 200 feet; it’s also the first ride I learned about in my classes.”

Flexible schedules

George loved her summer internship at Cedar Point so much that she extended it into late October — something she was able to do while still taking classes full time because of the flexible nature of the themed entertainment design major.

“In August I realized I wanted to keep working at Cedar Point,” she says. “Because the themed entertainment design program is asynchronous, I was able to do all of my classwork from Ohio while still working 30 to 40 hours a week.”

Asynchronous learning allows students to set their own schedule within a certain time frame. They can access and complete lectures, readings, homework and other learning materials at the time that works best for them.

This is a perfect fit for George.

“I am really into schedules,” she says. “I have three different planners that keep me organized. I am a detail-oriented person, and so it was not difficult for me to set aside a specific chunk of time for my classes while still working.”

Dynamic learning

The themed entertainment design major brings together multiple disciplines, which is one of George’s favorite things about the program.

“I love the combination of technology with leadership, operations and creativity,” she says. “It all comes together in themed entertainment.”

She is attracted to the management side of the industry. Many of her classes feature project management tools like Trello and Monday.com; she also explores the design side, which means using Figma, Maya 3D animation software, Adobe’s creative suite and SketchUp 3D modeling software.

“We learn about things like taking a building and turning it into a schematic so that we can adjust spaces and change the flow of people,” she says. “We are learning how to be visual and spatial storytellers, and design obviously plays a big role in that.”

George also says that many of her courses involve group work, which has been an easy way to make friends, through both in-person gatherings with students living in Indianapolis and online meetups with those who are taking classes from farther away.

“The class group projects are really fun,” she says. “As I have gotten deeper into my classes, everyone is super passionate about what they’re doing.”

George also appreciates the variety of venues explored in her major.

“One day you could be designing a high-thrill coaster; the next you could be creating an educational exhibit for 8- to 12-year-olds,” she says.

George sometimes refers to her major as “edutainment” because it combines education with real-world entertainment experience. Case studies and hands-on learning that supplement class materials are a key aspect of the program.

This semester George has been able to conduct case studies in partnership with The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. She takes photos and videos and jots down notes from a guest perspective to explore the storytelling and design techniques being used.

“My professors say that you can’t create exhibits without first experiencing them yourself,” she explains.

Knowledgeable, caring professors

One of George’s professors, Christian Rogers, selected her to be project manager for the Children’s Museum work this semester, which reflects the extent to which professors understand the goals of their students.