How Neil Armstrong ‘spawned lots of aerospace engineers’ with one giant leap

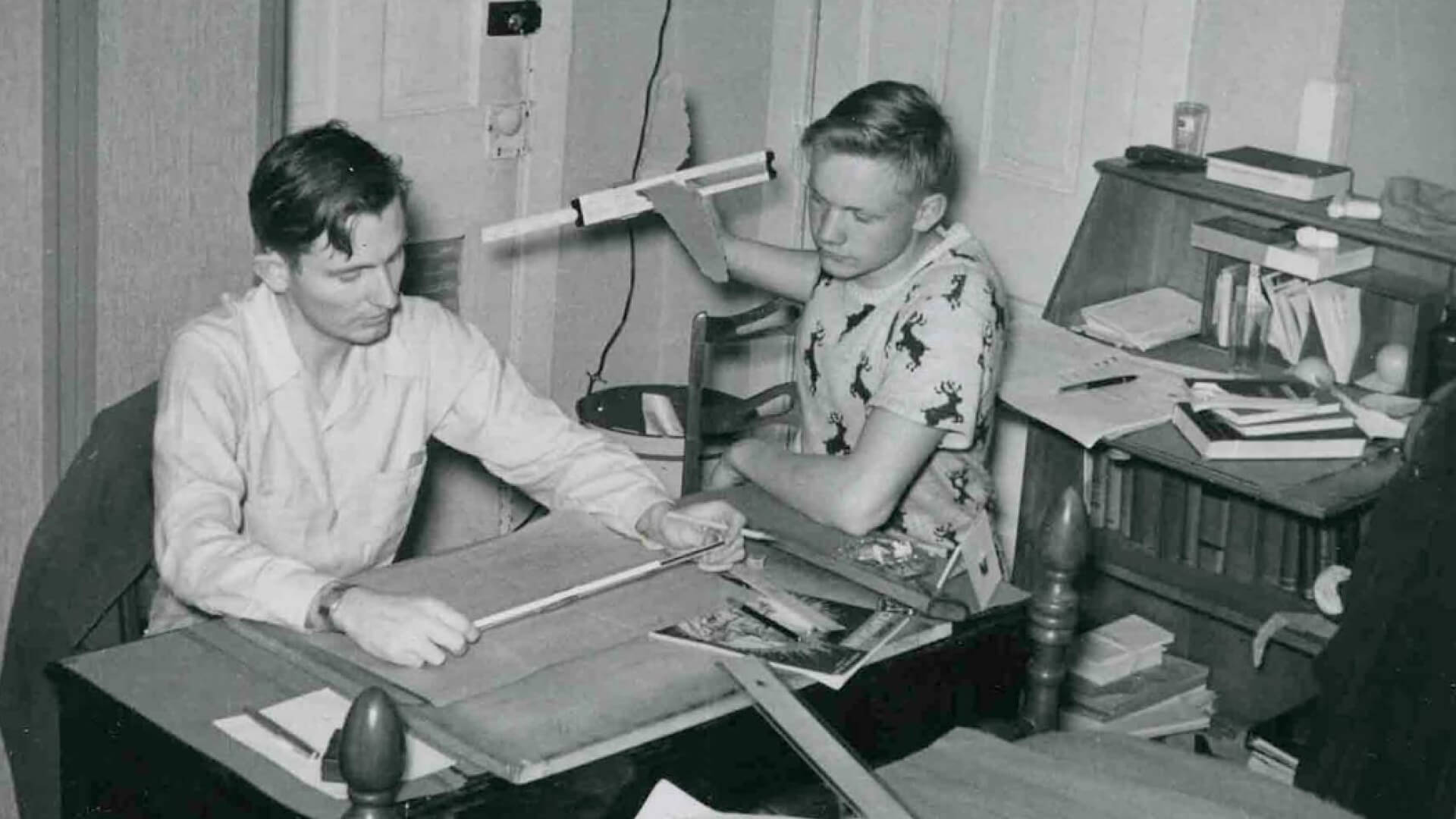

Purdue alumnus Neil Armstrong’s career as an aviator includes flying 78 combat missions in the Korean War, piloting the X-15 rocket-powered aircraft and commanding NASA’s Gemini 8 and Apollo 11 missions. (Purdue University photo illustration/Caitlyn Freville, sketch by Lilly Rile)

The legendary Purdue astronaut inspired people across the globe — and countless Boilermakers — to achieve the impossible

Only a few events are so important that all of humanity uses them to mark time.

Purdue astronaut Neil Armstrong (BS aeronautical engineering ’55) played the leading role in one such milestone — when his first steps on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission inspired awe and wonder across the planet.

“Neil spawned lots of aerospace engineers on that day,” says Purdue professor emeritus Stephen Heister, former lab director at the university’s world-renowned Maurice J. Zucrow Laboratories.

Like virtually everyone else who was alive at the time, Heister can tell you exactly where he was and what he was doing on July 20, 1969, when Armstrong first set foot in the fine lunar dust. Heister vividly recalls, as a 10-year-old, watching along with friends and family on a night where a full moon made it easy to see that same heavenly body where Armstrong and NASA colleague Buzz Aldrin had temporarily taken up residence.

Their achievement was, in Armstrong’s famous words, a “giant leap” that the entire world could share. An estimated global viewing audience of 650 million — roughly one in five people on Earth at the time — watched live as Armstrong landed the Eagle lunar module at Tranquility Base and then took his first steps on the moon several hours later.

Never before had a singular achievement so thoroughly reframed humankind’s perception of what was possible. Armstrong himself thought it seemed “almost beyond belief, technically” when President John F. Kennedy in 1961 announced America’s goal to land an astronaut on the moon by the end of the decade and return them home safely. Eight years later, Armstrong became that astronaut, completing a national quest to win the space race.

“It stamped an indelible mark on my life, on my imagination, and frankly, on the imagination of my generation and every generation since,” former Vice President Mike Pence said at the 2019 unveiling of Armstrong’s Apollo 11 spacesuit at the National Air and Space Museum. “It was a contribution to the life of this nation and to the history of the world that is almost incalculable.”

Boundless inspiration

Indeed, it is impossible to measure the full impact of the Apollo program, where courageous astronauts accepted life-and-death stakes while “sitting on top of a Roman candle, waiting for someone to light the fuse,” as author Tom Wolfe described liftoff in his book “The Right Stuff.”

However, a mountain of evidence reveals these pioneers’ vast influence.

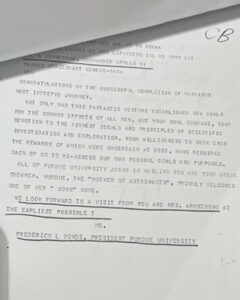

A few months after sitting spellbound in front of his television while watching the lunar landing, Mark Brown (BSAAE ’73) was a Purdue freshman watching in person as Armstrong accepted an honorary doctorate from his alma mater before a packed house at Mackey Arena.

In the coming years, Brown followed Armstrong into stints as a fighter pilot and astronaut who flew aboard two NASA missions. But at that moment, Brown felt encouraged that this plainspoken engineer from rural Ohio had once walked the same Purdue hallways and had gone on to participate in the most extraordinary technological achievement in history.

“It was so wonderful because here’s a brand-new aero engineering student watching probably our most famous alum be recognized for having come in the door as just a normal kid and eventually walking on the moon,” Brown said in a 2009 interview with Purdue. “It just doesn’t get any better than that.”

Letters preserved at Purdue

That sentiment is shared by legions of others who may not have gone so far as flying to space, but who were inspired by the astronauts all the same.

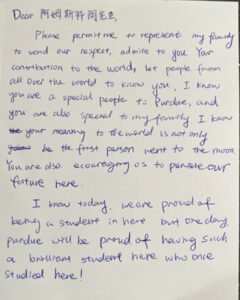

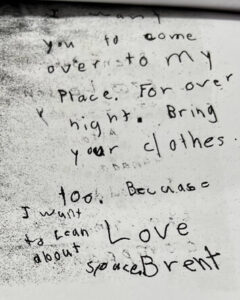

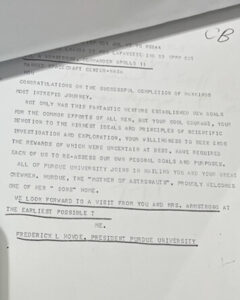

Many everyday people found something admirable in the quiet confidence and Eagle Scout’s integrity that they observed in Armstrong. Their adulation is evident in the more than 70,000 pieces of correspondence that Armstrong and his family donated to his alma mater as part of the Neil A. Armstrong papers that document his pre- and post-NASA life.

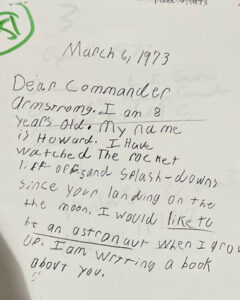

Most of these letters, forever preserved for public access at Purdue Archives and Special Collections, came from schoolchildren seeking photos, autographs and answers to simple questions about what space travel was like. However, many other pieces memorably exemplify the pride that so many derived from his feat.

A father in Paraguay wrote to share a picture of his daughter Luna (or “moon” in Spanish), who was born during Armstrong’s moon walk.

The children of Philip Nowlan, the sci-fi writer who created space hero Buck Rogers, wrote to say they watched Armstrong’s spaceflight and were thrilled to see “Buck Rogers finally coming to life.”

An artist from Beirut, Lebanon, wrote: “You were not alone in space. Millions of people were accompanying you with their hearts and souls while you were putting your foot on the ground of that white planet. The moment I saw you getting down from the module and stepping on the surface of the moon was the happiest and most pleasant moment of my life.”

And a letter from a female Purdue aerospace student and NASA co-op participant sought guidance on how she could also become an astronaut — seemingly a long shot in the early ’70s since no American woman flew to space before Sally Ride did so in 1983.

“I certainly have no doubts about women in space; I believe that to be inevitable,” Armstrong wrote back. “I hope you’ll speed the process along.”

This encouraging tone is present in many of Armstrong’s replies to his fan letters — particularly those from young people who hoped to follow in his footsteps someday. Although Armstrong was intensely private in his post-Apollo years, he enthusiastically supported his successors’ efforts to push the boundaries of human knowledge or accomplish the next ambitious goal that was once thought to be impossible.

“Neil was obviously very conscious of what he did. He knew what it meant to the country,” fellow Boilermaker astronaut Eugene Cernan (BS electrical engineering ’56) said in an interview with Cathedral Age after delivering Armstrong’s eulogy in 2012. “But I believe he personally wanted to focus on the future by trying to inspire young kids. He wanted to share himself in a way that they could relate to — not as this iconic figure who was the first human being on the moon.

“He had a way of delivering a presentation that I often called ‘Vintage Neil,’ as only he could do it: candidly, off the cuff, meaningful,” Cernan continued. “Sometimes I would listen to him and be amazed myself because this guy had done what people on this planet had only dreamed of doing for centuries.”

A humble engineer

Armstrong’s understated demeanor was among the key traits that made him an ideal candidate for the historic task he would eventually carry out.

He viewed himself as a test pilot and engineer, forever working to solve the next vexing challenge, but never as a celebrity who should have buildings named after him — not even at his beloved alma mater.

“He was such a humble and wonderful guy. I think that NASA absolutely made the right choice about who was going to be the first to set foot on the moon because he’s someone that we all can look up to,” says Heister, who jokes that he was uncharacteristically speechless the one time he met Armstrong as a Purdue professor. “He was not arrogant. He was not all about Neil. In fact, when Purdue went to design the (Neil) Armstrong Hall of Engineering, we said, ‘Neil, we’re going to name this Armstrong Hall.’ He goes, ‘Oh no, you don’t need to do that. Don’t do that.’ And it was like, ‘Neil, we’re going to do that.’”

Best of the American character

This was a brilliant aviator who obtained a pilot’s license before getting a driver’s license and who flew his preregistration papers from Ohio to the Purdue campus at age 16. He flew the first of 78 combat missions in the Korean War at 21. He was 30 when he began flying the X-15 hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft as a test pilot, reaching the edges of outer space at speeds up to 3,989 mph. And at 35, Armstrong saved his and astronaut David Scott’s lives by calmly activating Gemini 8’s reengagement thrusters, regaining control of the spacecraft after a malfunctioning thruster had caused it to violently spin out of control.

All of this before 38-year-old Armstrong took control of the lunar lander — the guidance system was carrying the Eagle toward the slope of a crater covered in huge boulders — and manually completed the Apollo 11 landing that made him arguably the world’s most famous person.

And yet anytime someone attempted to place Armstrong on a hero’s pedestal, he was quick to share credit with the 400,000 fellow Americans whose work helped him travel to the moon and back.

“Science and engineering isn’t about getting the accolades. It’s not about the ribbon cuttings and the high-fives, and it’s not even about getting credit,” historian Douglas Brinkley said during a 2014 lecture at Purdue about Armstrong’s legacy. “And that’s what he was always worried about: It’s about doing it and doing it right. An engineer can’t afford to mess up because lives are at stake. And so he really was the best of all things that I would call the American character.”

As well as one of history’s greatest examples of what a motivated group of engineers can accomplish.

“At the dedication of Armstrong Hall, he talked about his personal definition of engineering: that engineering is about what can be,” Purdue engineering’s former dean Leah Jamieson said in her introduction to Brinkley’s 2014 lecture.

“It is the single best definition of engineering that I have ever heard,” she said. “And Neil Armstrong, more than anyone in memory, gave us an unforgettable image of what can be.”