Eyes on the checkered flag

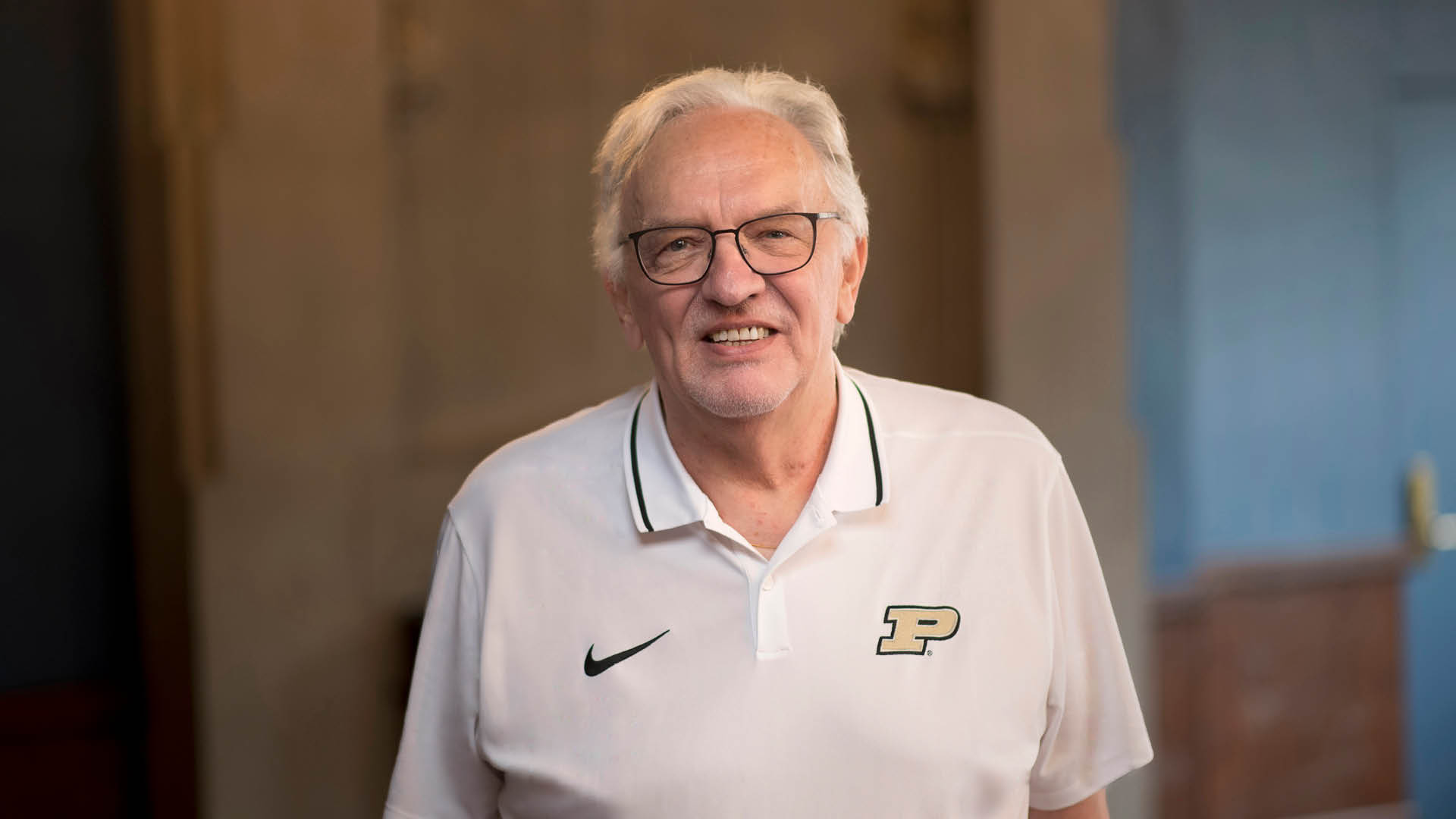

Rebecca Hutton is a Purdue motorsports engineering student in Indianapolis. (Photo courtesy of Chip Ganassi Racing)

Meet the Purdue students and graduates writing the next chapter in motor sports history

Many people enter motorsports dreaming of one day being on the winning team at the Indianapolis 500. Rebecca Hutton got to live it, just weeks into her internship with Chip Ganassi Racing.

“A lot of the engineers joked, ‘You’re one for one. Your first Indianapolis 500, you were on the winning team and on the winning car,’” Hutton reflects.

It was a remarkable moment for Hutton. Just three years earlier, she was working in pharmaceutical manufacturing with Sanofi Pasteur in eastern Pennsylvania. She made decent money, but it didn’t feel like it was the right long-term fit.

“I’ve always liked cars, always drove cars, and most weekends, I was out in the driveway working on my cars or my friends’ cars,” she says.

Then she got a push. Maybe you could call it a lightbulb moment. She was tuning into Netflix before heading to work second shift and caught “Formula 1: Drive to Survive.”

“I was watching the show, and I’m like, ‘Man, that seems awesome. What does it take to get there?’”

So she turned where most of us go when we’re hunting answers: Google.

“I’m at home ready to leave for work, and I just searched Google for ‘race engineer program,’ and — I kid you not — within the first five lines, I found Purdue’s motorsports engineering program,” Hutton says. “By the end of the day, I told one of my co-workers, ‘Well, guess I’m moving to Indiana.’

“At the time, I was 26 years old. I had to rearrange my life a little bit to move to Indiana and go back to being a full-time student. So I spent a year of my time kind of getting prepared.”

Regardless of Hutton’s meticulous planning, there was one important piece she couldn’t have anticipated: COVID-19.

“I moved to Indianapolis on May 1, 2020,” Hutton recalls. “Things were still closed. It wasn’t until Memorial Day weekend that restaurants reopened for the first time, but you could only eat outdoors. That was definitely a period of growth for me.”

Alone in a new city during a global crisis, Hutton kept her eyes focused on the path ahead of her at Purdue University in Indianapolis.

“Class, eat, sleep — Formula.”

Unlike Hutton, Purdue sophomore Zachary MacNab didn’t grow up with a passion for cars or knowing much about racing. In fact, he had plans to pursue a career in music production.

But, like Hutton, MacNab experienced something of an epiphany while watching “Formula 1: Drive to Survive.” It turned MacNab’s world on its head.

“That’s what introduced me,” he says. “It’s a really enticing sport.”

Although he didn’t have that childhood connection, MacNab credits his dad with helping him get his start.

“My dad always did his own work on mechanical systems like our lawnmower and woodworking tools,” MacNab explains. “He never really hired anybody to do things for him. So at a young age, I was exposed to mechanical systems and this idea of being very hands-on. I was decently comfortable working with my hands, so I was looking to take the next leap.”

For MacNab, that next leap was mechanical engineering. When the time came, he applied to a few schools, including Purdue’s West Lafayette campus, which he viewed as a “longshot.”

“Luckily, I got into Purdue,” MacNab says. “Even though this is a massive school, I feel very supported. I feel like I could go to any counselor or teacher. I’m not just another number.”

For MacNab, one of those key supportive figures is Todd Nelson, managing director of Purdue Motorsports and advisor to Purdue’s chapter of the Society of Automotive Engineers.

“He is hands down one of the best faculty members on this campus,” MacNab says. “He will do anything for students. He fights for us and advocates for us.”

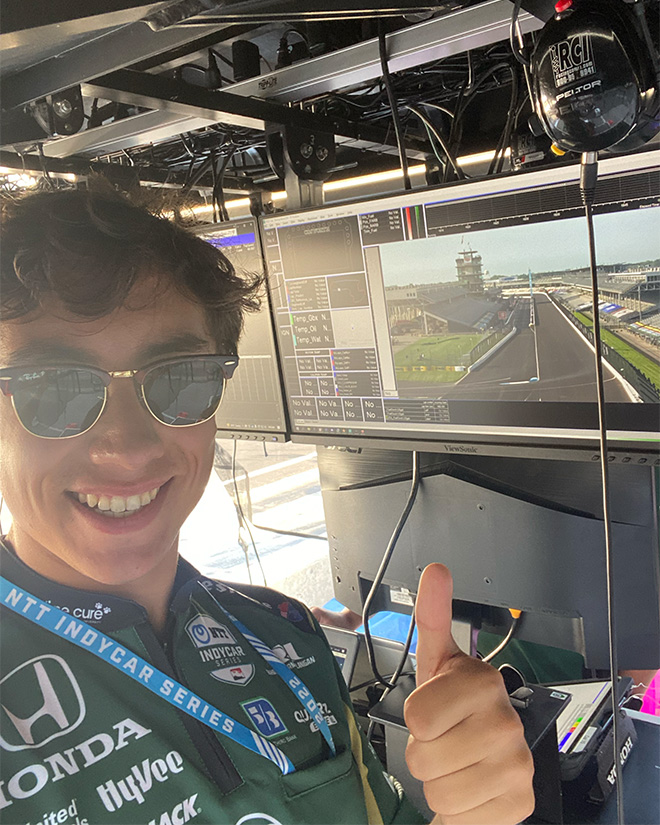

MacNab also credits Nelson with helping him land a simulation engineering internship last summer with Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing, based out of Zionsville, Indiana.

“I specifically owned and operated one of their driver-in-the-loop simulators,” MacNab explains. “With this simulator, the driver actually comes in and operates everything, almost like a video game. It’s helpful to feel out any setups that we want to try on the car or get the driver a little more refreshed on the course.”

The simulator was relatively new to the team, which meant MacNab carried additional responsibility.

“I needed to thoroughly document everything so that when I left, the engineers could still operate it clearly and efficiently.”

MacNab landed the internship just after his freshman year.

“At first, it was very daunting,” he shares. “They were throwing around terms I couldn’t understand. I kind of felt like, ‘Should I even be here?’ But I tried to stay calm and learn as much as possible. Looking back on it, it was a really valuable experience.”

While “class, eat, sleep, Formula” defines his daily routine, MacNab’s ambitions reach much further.

“One day when I’m looking back at my life, I want to be able to confidently say, ‘Yeah, I made this world a better place,’” he says. “I think that’s what life is all about, and the way I want to do that is through engineering and technological advancement.”

A special bond

Jennifer Short attended her first-ever Indianapolis 500 in 2012 at the age of 10.

“When I went to the Indy 500 for the first time with my dad, there was something about the atmosphere that was just electric,” Short says. “It’s one of the biggest sporting events in the world. You can tell everybody is so excited for the race — they’re still excited after sitting in the sun for two and half hours once it finishes.”

Her love for racing created a special bond with her dad.

“He was always a huge proponent for me,” Short says, “introducing me to engineering and things that aren’t necessarily considered feminine. When I went to my parents in middle school and said that I wanted to go to a STEM camp at Purdue for two weeks, they were so supportive.”

When it came time to apply for college, Short knew that she wanted to pursue engineering.

“Purdue was the obvious choice for me,” Short says. “I’ve been on campus so many times and just loved the atmosphere.”

Purdue passed Short’s “vibe check,” but she arrived still unsure of which engineering program to pursue.

“Part of the reason I loved Purdue was the first-year engineering program,” Short says. “When I came in, I was like, ‘OK, aerospace, industrial — maybe mechanical.’”

Short also joined the Society of Women Engineers her freshman year at Purdue. When an alumna came to give a tech talk, that was the first moment she realized that working in racing was a career possibility.

“She worked for Andretti Autosport on their IMSA LMP3 team, and she was talking about her degree and how mechanical engineering really helped her,” Short says. “I had this moment of, ‘Oh, my God, I can work on race cars.’ It never occurred to me that that was a career path.”

That moment sealed the deal.

“I was like, ‘Yup, that’s it. I’m going to be a mechanical engineer.’”

That experience led her to an internship with Andretti Autosport. Naturally, when she landed the internship, her dad was the first person she called.

“It was 11 o’clock at night, and my parents didn’t answer,” Short recalls. “I called my sister and said, ‘You need to get Mom and Dad.’ She was like, ‘Are you OK?’ I was like, ‘Yeah, you need to go get Mom and Dad, though!’”

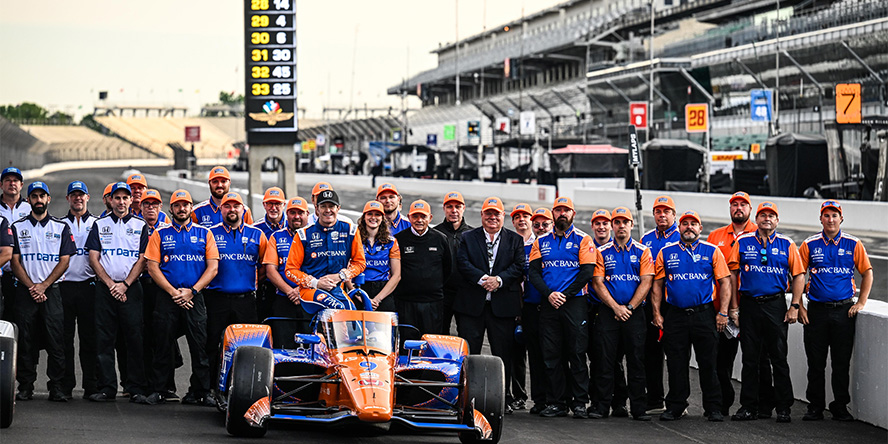

In 2022, Short interviewed for another internship, this time for Chip Ganassi Racing’s Women in Motorsports program.

“My interview went really well, and I walked out of there thinking, ‘I really want this job. I’m screwed if I don’t get it.’”

A week went by. Then two. She had been promised news in a week and a half, so Short sent an email.

“I got an email back at 10:45, and it’s from the guy that interviewed me saying, ‘Hey, Jennifer, I’m sorry it’s taking us so long. You’ll hear from HR tomorrow. I think you’ll like the response,’” Short says.

For the second time, a late-night call to her parents went unanswered, and she had to call her sister — “‘I’m not in jail, I’m not at the hospital — go get Mom and Dad!’”

Women in motorsports: ‘Part of the influx.’

Both Short and Hutton participated in the inaugural Women in Motorsports program with Chip Ganassi Racing. And both agree on one of the main obstacles to more women joining the industry.

Echoing a quote she heard, Short says, “It’s really hard to try and do something when your only role model is yourself in the future.”

“People have a hard time achieving things they can’t picture,” Hutton says. “If you’re not seeing women on pit lane winning the Indy 500, like Angela Ashmore (BS ME ’10, MS ME ’13) did last year, that won’t even be in your thoughts.”

The pace may be slow, but change is on the way — evidenced in part by Ashmore’s victory on Marcus Ericsson’s winning 2022 team as assistant engineer.

“I definitely am not at the forefront of women coming into motorsports, but I definitely am a part of the influx,” Hutton says. “Even between last year and this year, I’ve seen so many more women going over the wall as mechanics in pit lane.

“I was stopped by a woman at the Firestone Grand Prix in St. Pete, and she asked how I got into this. I told her, ‘There are tons of careers in racing, and if I can get in, so can you.’”

Just two weeks into her internship with Chip Ganassi, a man approached Short during a lunch break at the track to let her know what an impact she was already having.

“I was sitting outside with Rebecca eating lunch, and a guy walked up,” Short recalls. “He asked if I was Jennifer Short and said, ‘I saw you on TV last night. My daughter is 10. After watching that, she wants to be an engineer when she grows up.’

“I remember being 10 at the Indy 500 and not seeing any women unless they were wives or girlfriends.”

Encouraging girls to get started at a young age is crucial, Short says.

“Back in fifth grade, I was good at math, but I remember telling my teacher I didn’t want to be good at math because I wanted to be in a group with my friends. She told me, ‘No, you’re good at this, and you’re going to be in the higher math group.’”

And ultimately, Hutton says, bringing diversity to the field is never a bad thing.

“People have different perspectives on how to problem solve,” she says. “That’s a product of where they came from. And as engineers, all we do is problem solve and look for more solutions.”

People have a hard time achieving things they can’t picture. If you’re not seeing women on pit lane winning the Indy 500, like Angela Ashmore did last year, that won’t even be in your thoughts.

Rebecca Hutton

Senior, Motorsports Engineering

Climbing up the ranks

Alex Offenbach was just 13 when he got the racing bug.

“The first time the cars went by, my life changed,” says Offenbach (BS MDE ’16), assistant engineer with Chip Ganassi Racing. “I decided that second, this is what I want to do. If I want to be an engineer, I want to engineer those because that was the coolest thing I’ve ever seen.”

The epiphany he had in the stands that day at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway wasn’t a passing phase. Before long, he would follow his dream to Purdue.

“As time went on, I started to hear about the partnership that Purdue had with one of the IndyCar teams,” Offenbach says. “I already had Purdue in mind because one of my cousins went there, and I knew it was a good engineering school. Now they have ties to the IndyCar community? That couldn’t be more perfect. When it was time to apply to colleges, I knew I wanted to apply to Purdue. I had nothing else in mind — no backup plan.”

If engineering race cars was the goal, Purdue was the path. As Offenbach saw it, it was “Purdue or nothing.”

“I came to campus super interested in Grand Prix,” Offenbach says. “So, I joined a fraternity to get involved in that and drove in it twice. You know, it’s just so funny to look back knowing what I know now working in professional racing. I laugh because I can’t believe they let what I put together go on the track.”

If there’s a word to describe Offenbach’s career trajectory, it may be determination. From that first Indy 500 in 2006, he never lost sight of his goals, through all the ups and downs along the way. And that persistence yielded unique opportunities.

“I was super-committed to getting into racing, no matter what it took,” Offenbach says. “All through high school, I was drawing racetracks on the back of my school notebooks.”

After graduating, he hadn’t landed his dream job. He was in North Carolina, working without a contract and without pay on the lowest rungs of the industry.

“I went to North Carolina, worked on some pavement midget cars for a guy that I’d met,” Offenbach says. “Basically, I worked for him and, in exchange, he fed me and let me stay at his place.”

Then he got a call.

“IndyCar track designer Tony Cotman gave me a call out of the blue and says, ‘Hey, Alex, I’ve got a couple of big projects coming up. I’d like to hire you.’”

Going into it, Offenbach knew that this wouldn’t be a long-term deal. There is only so much development going into track design at a given time. Nonetheless, it was a turning point.

In 2017, that same year, he made a promise to himself from the stands of the Indianapolis 500.

“I felt like I was so close,” Offenbach says. “I worked the minor league event ahead of the Indy 500 when Takuma Sato won. I told myself, ‘Whatever I do, I have to make sure I’m working the Indy 500 next year.’ And I did. I haven’t watched one from the grandstand since — and the cool thing is that we get to work together at this year’s Indy 500 at Chip Ganassi Racing.”

I told myself, ‘Whatever I do, I have to make sure I’m working the Indy 500 next year.’ And I did. I haven’t watched one from the grandstand since.

Alex OffenbacH Assistant Engineer, Chip Ganassi Racing

‘It’s cool to see you here.’

Both Offenbach and Hutton work for the Chip Ganassi Racing team.

“I was excited when I found out I was going to be able to work with her,” Offenbach says. “We both understand the Purdue engineering way of doing things. Purdue engineering sets you up to look at the fine details.”

Hutton shared Offenbach’s determination — as well as a conviction that whatever curves, bumps or obstacles she may encounter, she was on the right path.

Being in Indianapolis meant that she was in the heart of the action with top industry professionals for professors.

“They know a lot of people, and racing is a small industry,” Hutton says.

She’ll never forget a moment that drove home the importance of networking.

“I remember my first day in the motorsports program. In a class with one of our professors, he talked about networking and made it a point to say, ‘Network here, because these people are going to be the people that you’re working around,’” Hutton reflects. “And I’ve already seen that. I work with three people I went to school with, and when I went to the race yesterday, I saw another three people I’m currently in school with.”

From a major career shift to moving to a new city in the middle of a pandemic, Hutton’s journey to Indianapolis wasn’t what you might call conventional. But it was uniquely her.

“As a woman in a male-dominated field, I’ve been mentored by [Purdue grad] Angela Ashmore, the first woman to be on a winning team at the Indianapolis 500,” Hutton reflects. “Who can say that? I liked her when I interviewed her for class two years ago. Then later, as an intern, I sat down at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway next to Angela. She turned to me, and the first thing she said to me when we spoke: ‘It’s cool to see you here.’ She remembered that interview. She remembered me.

“I couldn’t have written these past three years better than how they’ve turned out. I am working at one of the top IndyCar teams alongside people that I am going to learn a heap from and help spark my career more than it already has been.”