Building a high school from the ground up

How an educator increased pathways to college by reinventing the high school experience

INDIANAPOLIS — When Scott Bess took to the podium for Purdue Polytechnic High School Schweitzer Center at Englewood’s first commencement on June 11, he paused, looked out at the graduates and their families, and had to compose himself.

“There were a lot of emotions that day, that’s for sure,” Bess says. “I’d see faces of students that I remembered when they walked through the door that first day.”

Bess, the founding executive director of the Purdue Polytechnic High School (PPHS) network and a recent appointee to the Indiana State Board of Education, says the first graduating class is the one he knows the best – mainly because they started their PPHS journeys together.

“I know their personal journeys and evolution. They were shy and timid when the school opened, and to see them doing what they are doing today – there’s a ton of pride in what the students were able to accomplish,” he says.

Persistence and inspiration

Bess’ path to that moment on a stage in front of the PR Mallory Building at 3029 E. Washington St. in Indianapolis began on a 500-acre farm in his hometown of Monon, Indiana.

Like many teens, he didn’t know what he wanted to do with his life. He knew he was good at math, so after talking with his high school guidance counselor, he set out to be an actuary. But parental influence eventually won out, and he wanted to be a teacher.

His mom had dropped out of college to marry his dad, who was in the Army. After numerous moves, his mom enrolled at Purdue to finish her teaching degree.

“As a young kid, I got to see her go to school and get that first teaching job. The work she did was inspiring,” Bess says. “She showed us there’s a lot of education that happens outside the lines.”

Her dedication to her students served as the spark and inspiration that spread throughout the family and has become a family business, of sorts: Both his sister and brother are also teachers.

After receiving his math degree with a teaching endorsement, he set out on another leg of his education voyage.

The stepping stones

After teaching in Beech Grove (Indiana) City Schools, working in information technology for a utility company and running a consulting business, Bess was named chief information officer for Goodwill and also was elected to the school board of the Danville (Indiana) Community School Corp.

Following passage of Indiana’s charter school law in 2001, Goodwill – an organization that works to help people get jobs and raise their personal standard of living – opened a charter high school. And Bess was involved in setting that up.

“I stayed engaged in education,” he says. “I had a mentor teacher at Beech Grove once say to me, ‘You can leave teaching, but … you’ll never leave education.’”

He continued reinventing educational experiences for teens and adults, even during one of the financial low points in American history.

During the Great Recession of 2008, Bess and others at Goodwill confirmed that more than half of the people they worked with in low-paying, unstable jobs did not have high school diplomas.

Bess was part of the team that established the Excel Center in Indianapolis in 2010, which provided schooling around adult learners’ needs. In addition to accelerated classwork throughout five semesters a year, the center would provide life coaches and on-site child care.

“People don’t drop out because they aren’t smart. They drop out because of all the other things that happen,” he says.

Goodwill expected 250 adult learners that first year. It ended up with 350. Currently, there are more than 40 Excel Centers across the U.S., which graduate almost 3,000 adult learners a year.

The small step that turned into a giant leap

Through Goodwill, Bess worked with others on navigating the charter school landscape. Purdue officials contacted him about opening a public charter school in late 2015.

In those conversations, Bess shared his concepts of reimagining the high school experience.

“You have to answer a fundamental question: ‘Do you want to start a STEM high school with Purdue’s name on it, which would be great and successful, or do you want to fundamentally reinvent the high school experience?’”

Following several conversations in 2016 – including a two-hour meeting with Purdue President Mitch Daniels – Bess was hired to start a high school from the ground up.

The university created PPHS to build new K-12 pathways that lead to Purdue, especially for Hoosier students who are underserved by traditional high schools and underrepresented in higher education.

The growing, multischool PPHS system immerses students and their families in an innovative learning community. PPHS offers tuition-free, authentic, STEM-focused experiences that prepare high school students for a successful future. These experiences include internships, industry projects, dual-credit courses and technical certifications. PPHS also offers its students a unique path to college; graduates who achieve Purdue’s admission requirements are assured admission to many programs at Purdue.

Bess says there are ways to reinvent the high school experience that people agree upon – the need for more collaboration, hands-on learning, engagement between students and teachers, meeting standards and addressing time limitations.

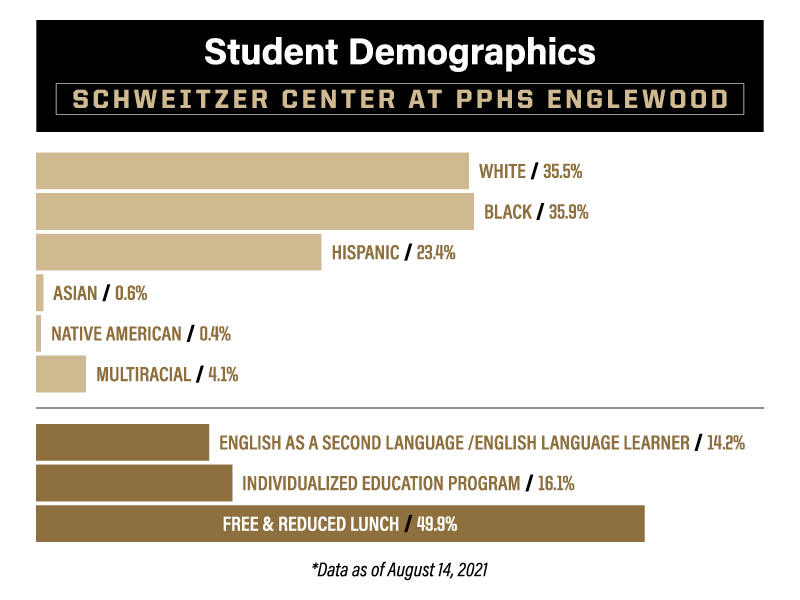

One of PPHS’ goals is to change that model and to empower students in their educational cycle, including those students who come from underrepresented minority communities, and community and business partnerships (watch the video of the journey to commencement). PPHS Schweitzer Center at Englewood is an innovation school through a partnership with Indianapolis Public Schools. PPHS North and PPHS South Bend are public charter schools.

Opening doors for students, families and new schools

While Bess was recruiting families and designing curriculum, he and other school officials still needed to find a place to house the school and hire staff.

One of the first teachers recruited by Bess was Drew Goodin, lead instructor at PPHS Schweitzer Center at Englewood. Goodin met Bess in spring 2017 at the Indianapolis Showcase of Schools event. Goodin was in the process of moving to Indianapolis and was searching for a teaching job. He was intrigued by Purdue being at the event.

“I met Scott, and he sold me on the vision of PPHS immediately,” said Goodin. “After I left, I called my wife and said, ‘I need to teach at PPHS.’”

Goodin was there with Bess when the doors opened on July 31, 2017 at PPHS’ temporary home in the Union 525 Building to 150 students.

One of the great moments of that first day, he says, was everyone knowing that this was new – coaches (what PPHS calls teachers) and students both learning their ways around the building and about each other, and setting the school’s culture of collaboration, communication and innovation.

“We did a lot of tinkering and experimenting and trying to figure out how to make things work. They did a magnificent job of pulling it together,” he says. “But it was a ton of fun.”

The second-year created many challenges – including relocating to the Circle Centre Mall in downtown Indianapolis thanks to rapid growth and improving upon first-year practices – all at once.

“We put things in place that were complicated. We tried to force-fit some of the academics into the projects, and the students recognized immediately that it wasn’t real,” Bess says. “The students caught on.”

Addressing those issues head on in that moment is when Bess saw the school community come of age.

“The flexibility and adaptability of the staff carried forward and helped cement the culture with our students as well,” he says. “We learned that you can’t make artificial projects. Students have to have a voice and choice for their projects. That’s where most of what we do today started to take shape in that second year.”

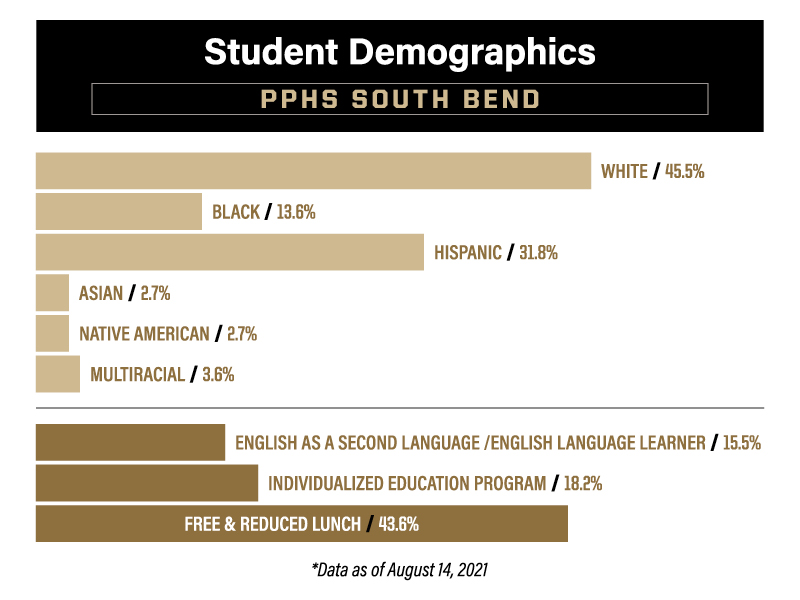

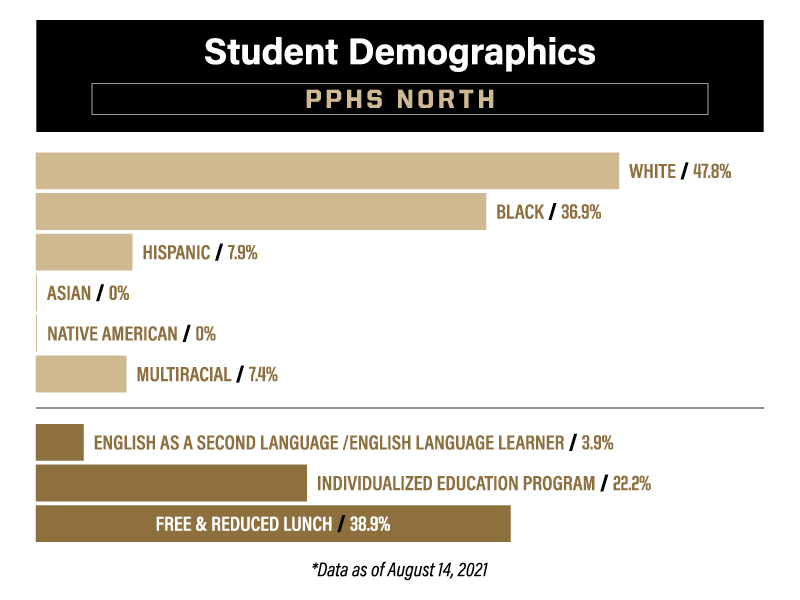

PPHS has opened two other locations – PPHS North in Indianapolis’ Broad Ripple neighborhood in 2019, and PPHS South Bend in 2020. PPHS is working with Indianapolis-based real estate developer Keystone Group in securing a new location in Broad Ripple, where it can grow to up to more than 400 students. The South Bend location shares space with Purdue Polytechnic Institute’s statewide location in a former Studebaker plant in the Renaissance District.

Bess’ innovation, persistence and even-keeled demeanor is noticed by the staff in a variety of ways.

“Scott has such a knack for flying at all altitudes. You can bump into him in the hallway and the conversation might lead to discussion about the long-term vision of reinventing high school or the nitty-gritty of a curriculum component,” Goodin says. “Then his phone will ring and it will either be a state legislator consulting him for his perspective on a bill or a contractor asking a construction question.”

Goodin says the coaches, staff and students have learned a lot over the past five years, especially now that the first class has graduated and is off to apply the innovative problem-solving techniques they learned and practiced at the school.

“Scott is the vision keeper. The pull toward ‘traditional’ school is strong, and it’s easy to get lost in the minutia and ‘reinvent’ back to traditional, which we know doesn’t work for historically marginalized students,” Goodin says. “Scott wears many hats, but the hat that’s on tightest is when he’s coaching and nudging us to stay true to our vision.”

Bess is grateful to families and staff who have taken risks in being in the first classes at both locations. “All of them took a chance on something sight unseen,” he says. “We’re seeing a real positive growth and seeing some good inroads into the communities we serve.“

Thirty-seven students from the first graduating class at PPHS Schweitzer Center at Englewood are enrolled at Purdue for the fall 2021 semester. Others in the class decided on attending other higher education institutions.

While Bess says the goal is to build a pipeline to Purdue, it’s also important for the students to become more confident and advocate for their needs on their individual educational paths.

“We want students to be successful wherever they go,” he says. “The problem-solving ability of these students is off the charts compared to other students. They have the skill sets to solve problems without giving up.”

Next steps and leaps

Reflecting on PPHS’ goal of addressing the needs of underserved and underrepresented students, Bess says those issues are not just an Indianapolis issue. They are present all across urban and rural Indiana school districts and communities.

“There’s an unacceptable low number of low-income and Black and brown students who are qualified to get into a place like Purdue,” he says. “There is a preparation gap. We’ve figured out a way to close that preparation gap where we provide opportunity for everybody.”

PPHS is looking for partners across the state for a variety of models – ranging from a STEM-themed high school that addresses the preparation gap to working on certain elements of STEM education.

Education leaders and elected officials from across Indiana and the U.S. frequently call Bess to talk about what PPHS is doing to improve secondary education.

“If you dare to do something, people pay attention,” he says.

But the curiosity doesn’t stop at the high school. He cites Purdue’s commitment to affordability by continually freezing tuition and increasing enrollment.

“I think we see some of the same things in the K-12 space. People are intrigued by what we are doing, but are really scared to take the plunge. What we’re doing is we will help people into the water bit by bit – just do a piece of it,” Bess says. “By the end of the journey, they are fully immersed.”