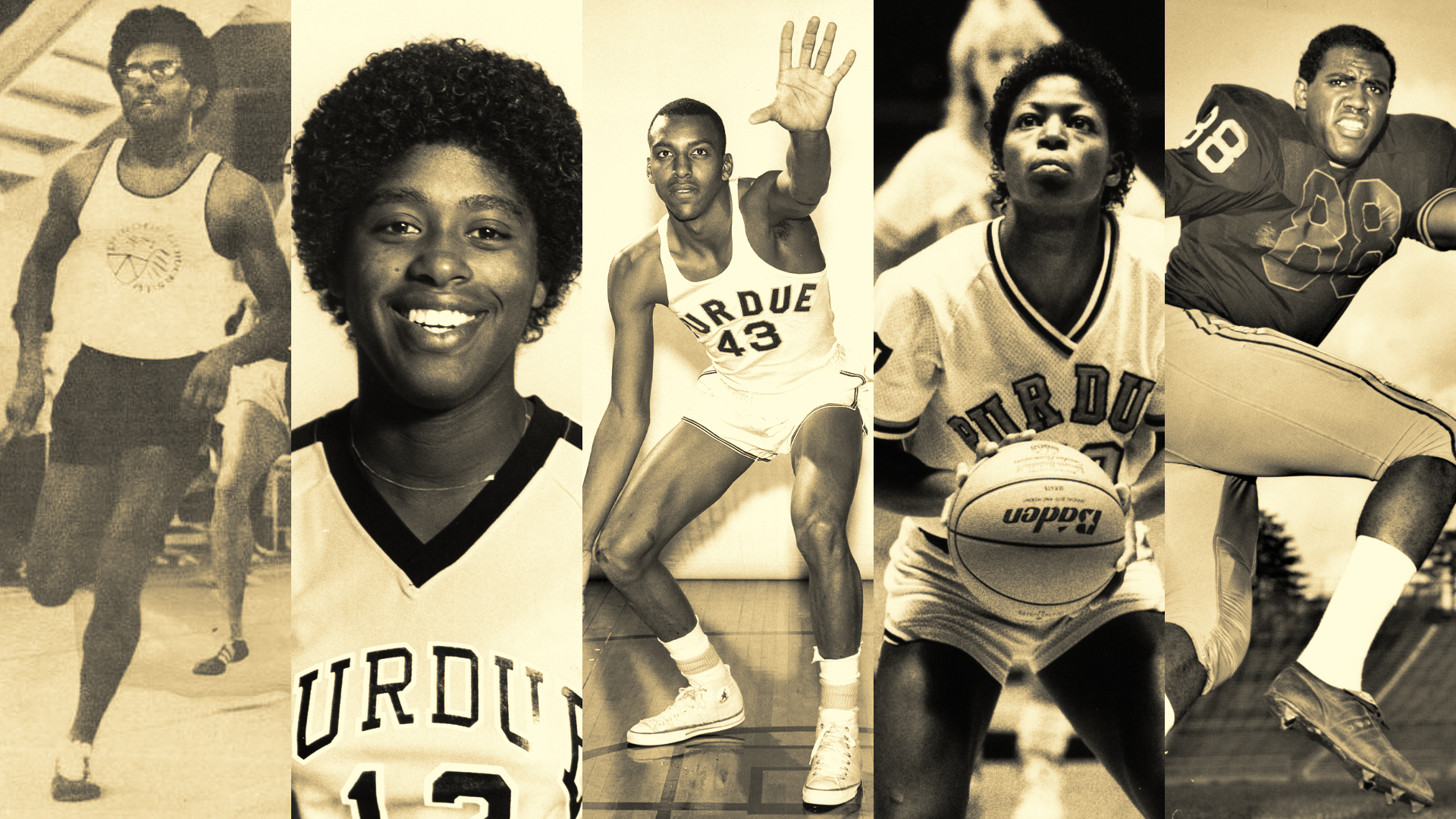

Black pioneers who shaped Purdue Athletics

Five Boilermakers reflect on what it was like to be a Black student-athlete at Purdue

Pioneers.

There have been many in Purdue Athletics history. But perhaps none more important than those among the first Black student-athletes to compete for the Boilermakers.

The list of five former Black Purdue student-athletes below is just a sample of the stories of many who forged their path. Each agrees that Black History Month is the time to honor and celebrate the diverse experiences and perspectives of their time at Purdue. It is also time to educate.

“I think the celebration of all history is important, and it is important at least for one month that people take the opportunity to study our Black heritage, our culture,” says Roland Parrish, a standout track athlete at Purdue from 1971-75.

“We all had experiences, and we all had challenges.”

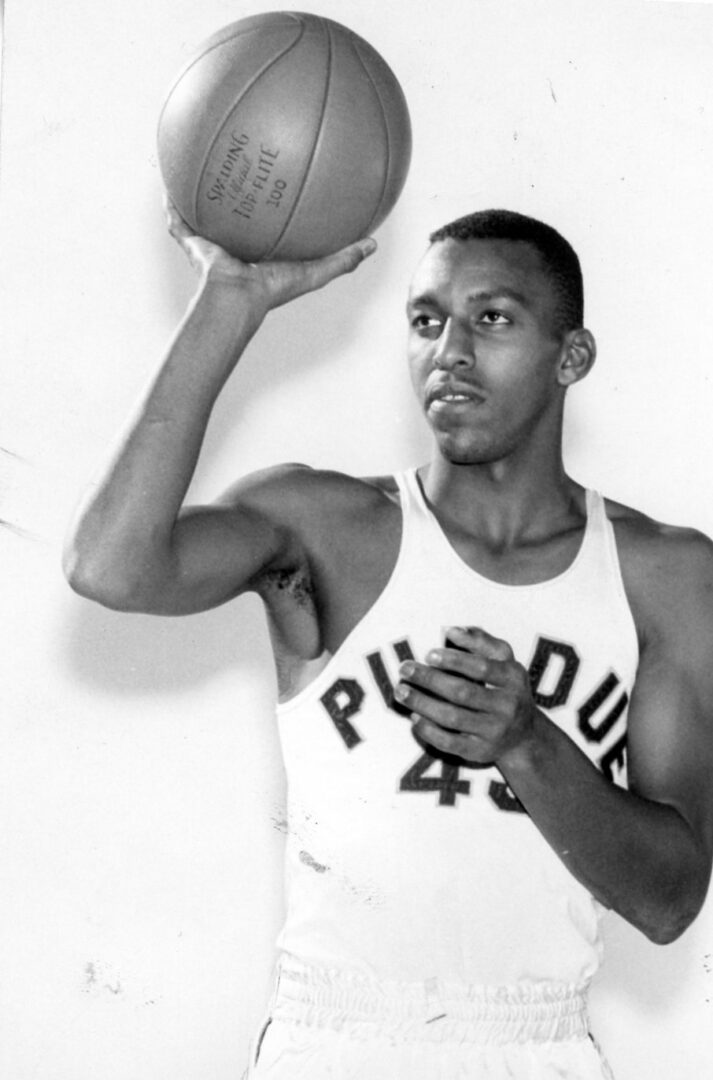

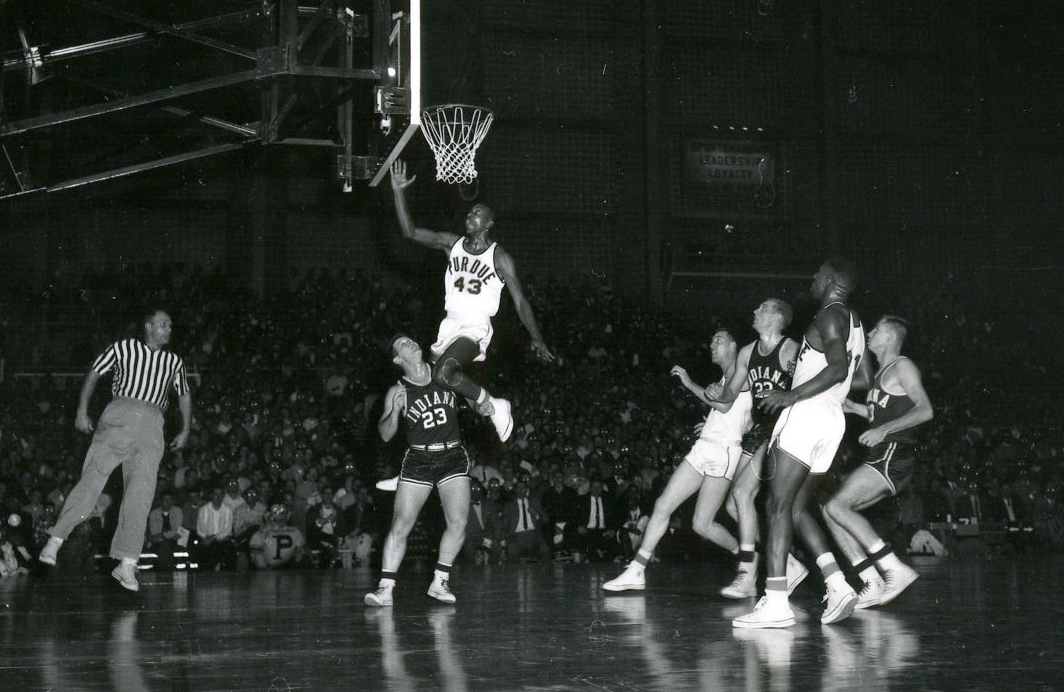

Willie Merriweather, men’s basketball, 1957-59

A teammate of Oscar Robertson at Crispus Attucks High School, Merriweather was a standout player for coach Ray Eddy. He was good enough to be inducted into the Purdue Athletics Hall of Fame, averaging 20 points per contest in his senior year. He played at Purdue during the first large influx of Black basketball players, crossing paths with Lamar Lundy, Wilson “Jake“ Eison, Harvey Austin and Charlie Lyons.

“It was great to have those guys as teammates, and I had a good experience at Purdue,” says Merriweather, who went on to have a four-decade career as an educator in Detroit. “We were treated well as athletes. We adjusted to how things were then, even when told by Coach Eddy that they couldn’t simultaneously play more than a couple of us (African Americans).”

Socializing was not easy for Black people on Purdue’s campus in the 1950s, when students of different races were not treated equally.

“So we focused on our studies, and I was proud to make the dean’s list,” Merriweather says. “It meant a lot to me to be a good student.”

Merriweather has enjoyed watching all the changes that have occurred for Black athletes and all athletes in the past 60 years.

“It’s a whole different world today for the kids,” Merriweather says. “I am glad most people celebrate our history. It’s not perfect by any means, but having the opportunity to play when I did, I had some role in making things better for those that came after me.”

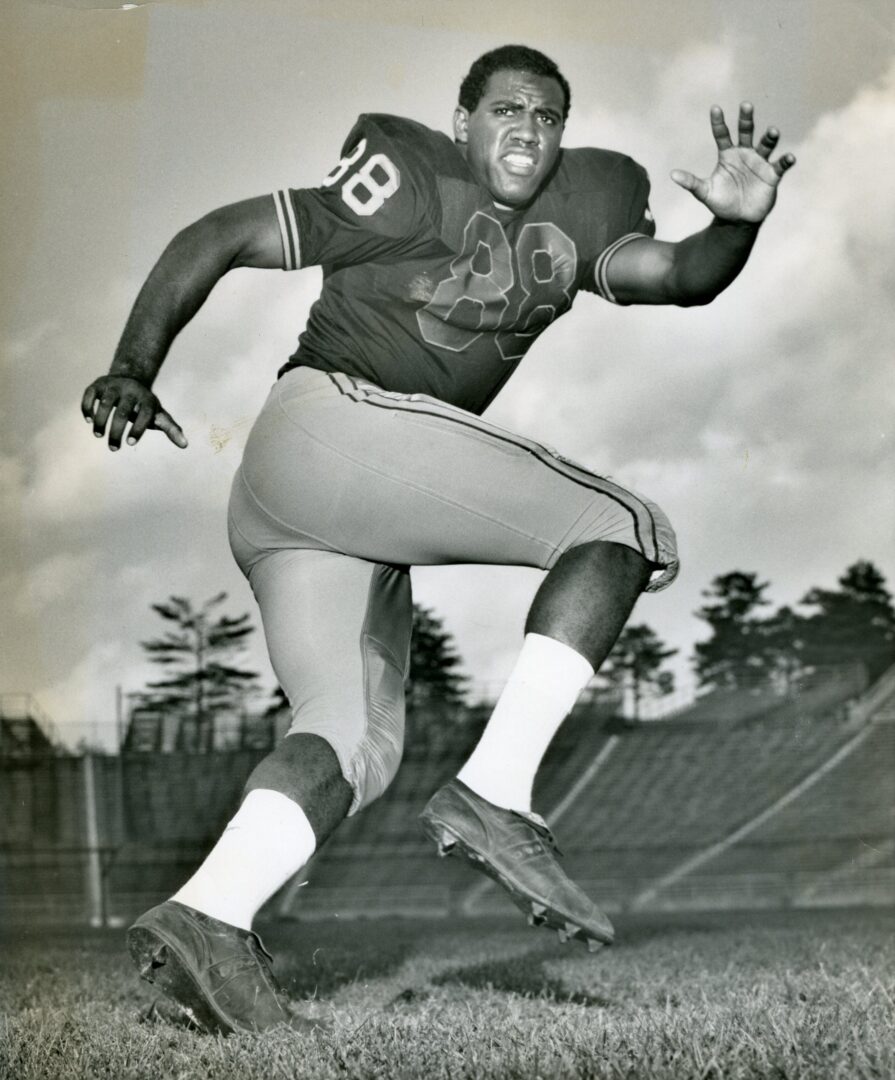

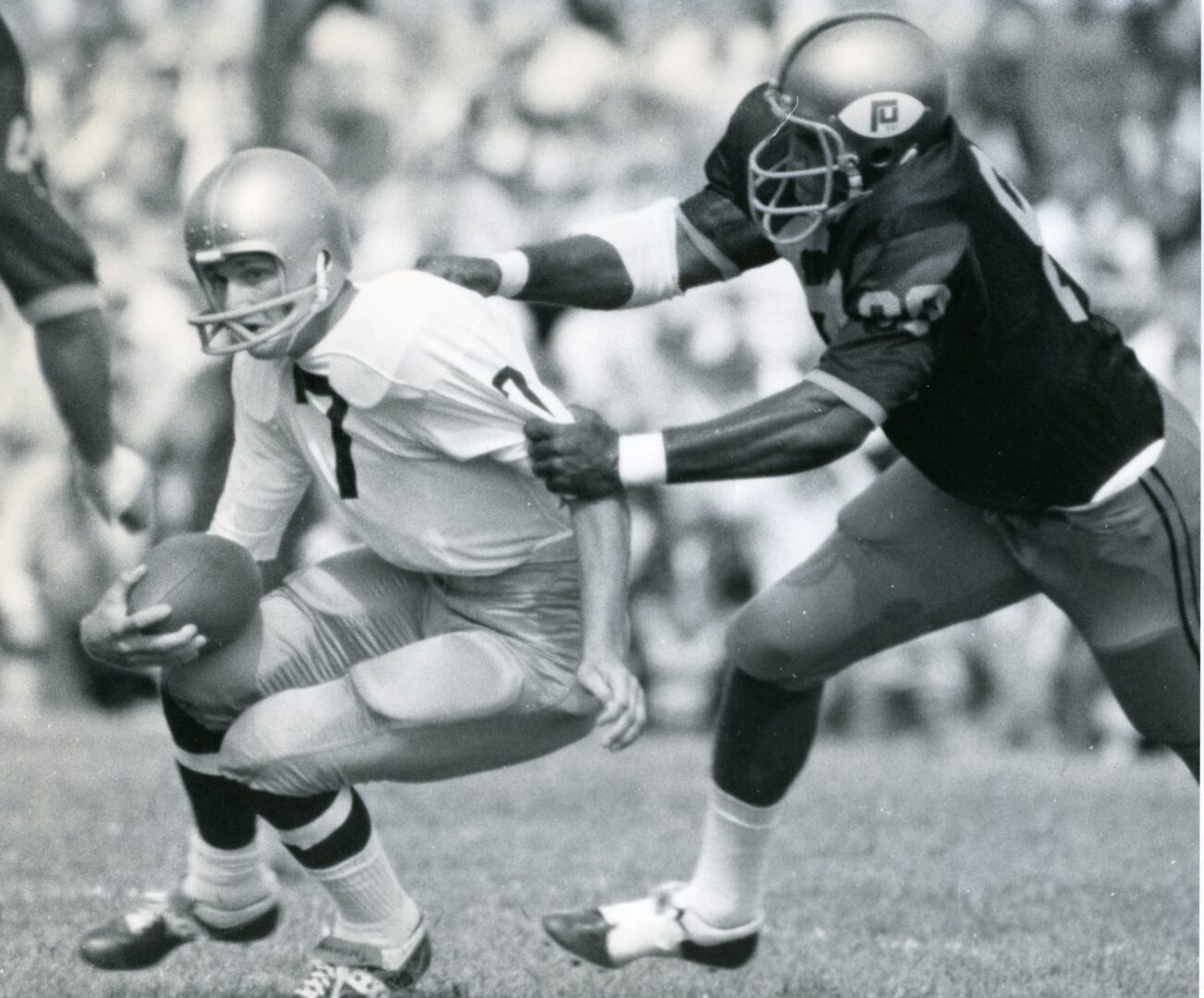

Billy McKoy, football, 1966-69

William (Billy) McKoy was a standout defensive end for coach Jack Mollenkopf and played for Boilermaker teams that compiled a 24-6 record from 1967-69 and won a Big Ten championship. Additionally, he was part of the first program in college football to beat Notre Dame three consecutive seasons.

Coming to Purdue from the segregated South was initially a shock for McKoy, a native of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The same school had produced Herman Gilliam to Purdue a year earlier. Purdue football had been integrated in the 1950s and produced Lamar Lundy, the only Boilermaker to earn MVP honors in football and basketball in the same school year.

“I credit my good experience to Coach Mollenkopf because the team was like a family, and he created that environment,” says McKoy, who went on to play in the NFL for the Denver Broncos. “It was seamless. Despite the racially charged times, our team had no racial hiccups.”

The environment on campus was mostly a positive experience for McKoy, although he recalls a few unpleasant interactions with fellow residents of Wiley Hall and professors who didn’t always embrace his perspective.

“My high school teachers had me ready for college, so I was confident I could do college work,” says McKoy, who ended up with a several-decade career in human resources and as senior vice president for operations at the YMCA in Atlanta. “But it was an adjustment for all of us.”

The importance of Black History Month is not lost on McKoy.

“I am a glass half-full person, but there are some places where people are trying to change the narrative of our history, and that is concerning to me as it should be to everyone,” McKoy says. “It remains unfortunate that we are still hearing too many times, ‘This is the first African American to do this, this is the first African American to do that.’ I thought we might be further along in my lifetime.”

McKoy cites one of his best moments as his long-time relationship with a teammate who had never met a Black person before he came to Purdue.

“The fact that we are still friends today is important to me,” McKoy says. “One of the things about ‘ball’ is you had to figure out how to win the game that was in front of you. Winning, however you define it, was what it was all about. That helped me survive and thrive at Purdue.”

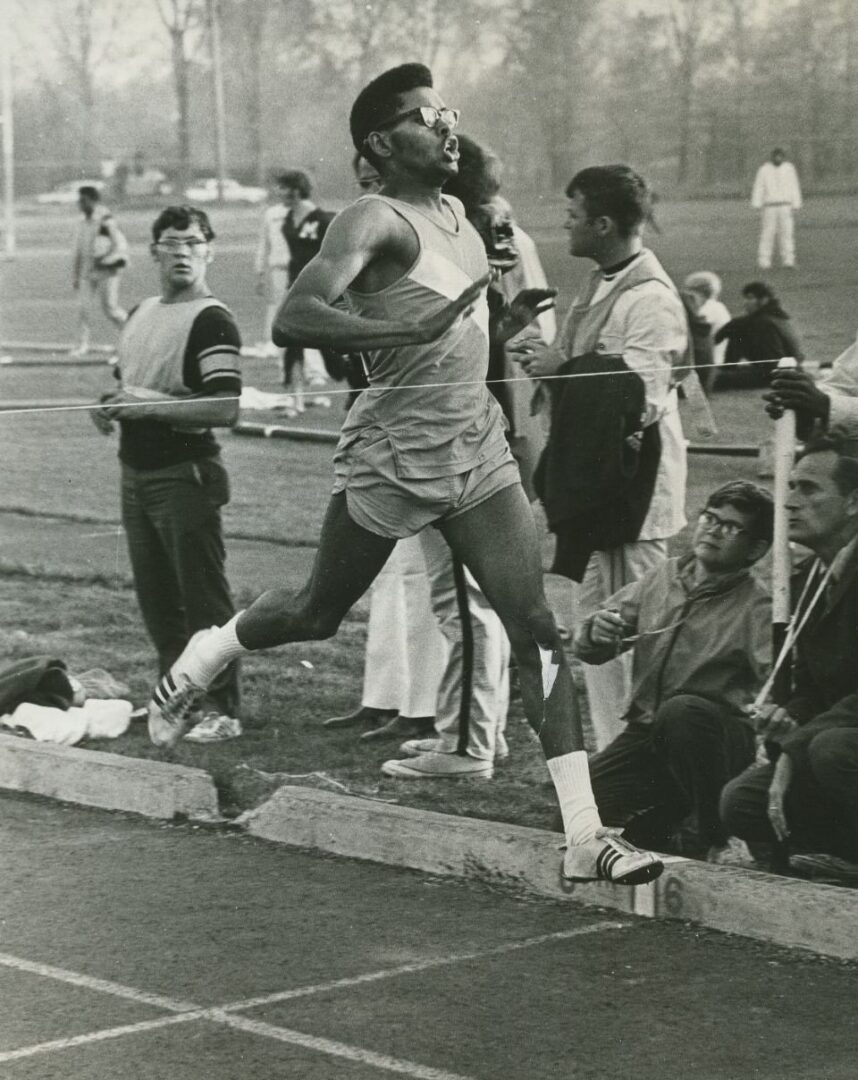

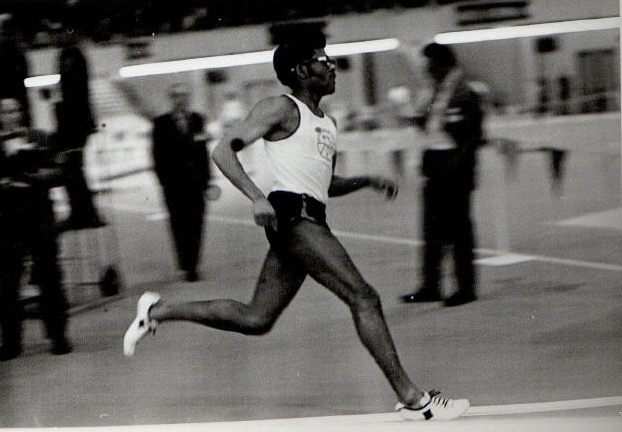

Roland Parrish, men’s track & field, 1971-75

A native of Hammond, Indiana, Parrish came to Purdue on a full-ride track scholarship. After growing up in a Black neighborhood, the middle-distance runner attended Hammond High School, which was only about 3% Black.

“Coming to Purdue wasn’t the culture shock for me as it was for many people of color,” says Parrish, who was voted team captain and twice earned team MVP honors. “Back then we didn’t have Black coaches for mentors, but I was very fortunate to have Dr. Cornell Bell, the head of Purdue’s Business Opportunity Program (BOP). He was a no-nonsense man who didn’t let you make excuses.”

Parrish credits Bell and others for helping him be disciplined. He studied, went to track practice and was a musician for the Second Baptist Church in Lafayette, where he played keyboard on weekends.

“I believe in the saying, ‘The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing,” Parrish says. “When I break it all down, it is really that simple.”

In Parrish’s mind, Black History Month is a time to recognize the people that came before. In athletics, Parrish was forever touched by the life and times of Leroy Keyes, Purdue’s two-time All-American football player who came to campus six years before Parrish.

“I always looked up to Leroy and I stand on the shoulders of those who walked in my shoes when things weren’t quite as evolved as they were when I was in school,” Parrish says. “Even 40-plus years later, Purdue continues to evolve. I like what I see out of the university regarding race, but there are always paths to travel for improvement.”

Parrish has had a stellar business career, which includes owning more than two dozen McDonald’s franchises in North Texas near his Dallas home. He has given time and treasure back to Purdue in many areas, including funding a renovation of the former Management and Economic Library a dozen years ago. He has also funded a scholarship in Bell’s memory and remains devoted to the Keyes family after Keyes’ passing in 2021.

“There were challenges for Blacks when I was at Purdue,” Parrish says. “But I look at all the programs available to Black kids today and all the role models that Purdue’s athletes have access to, and that makes me hopeful that we are making progress.”

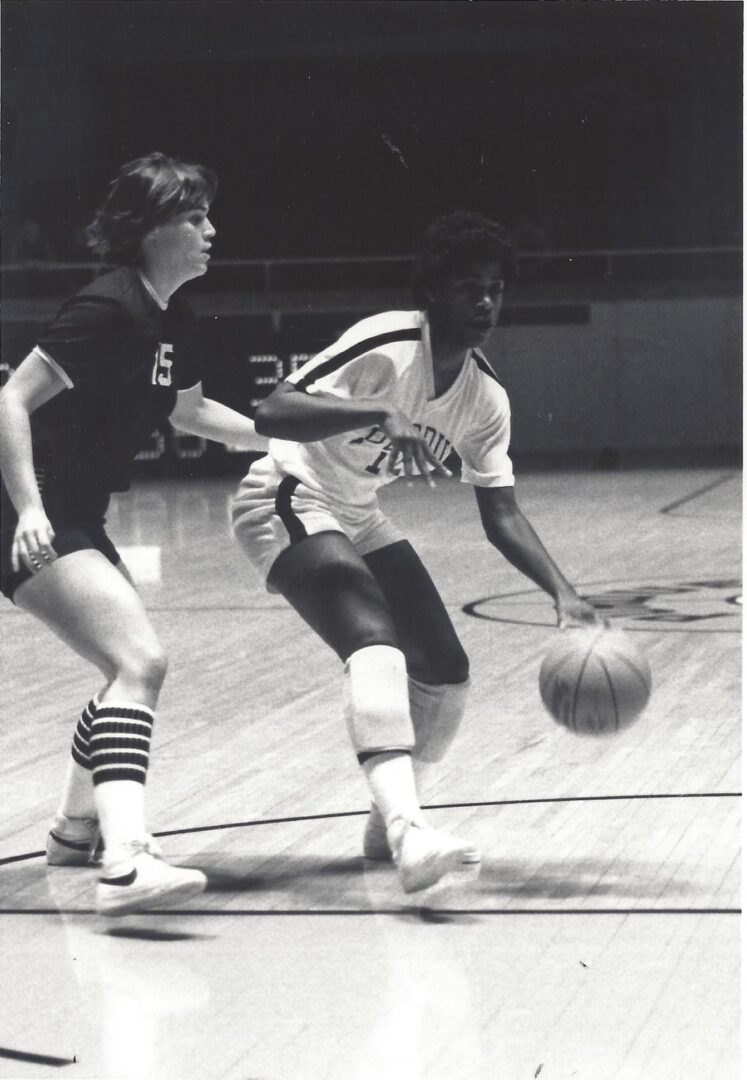

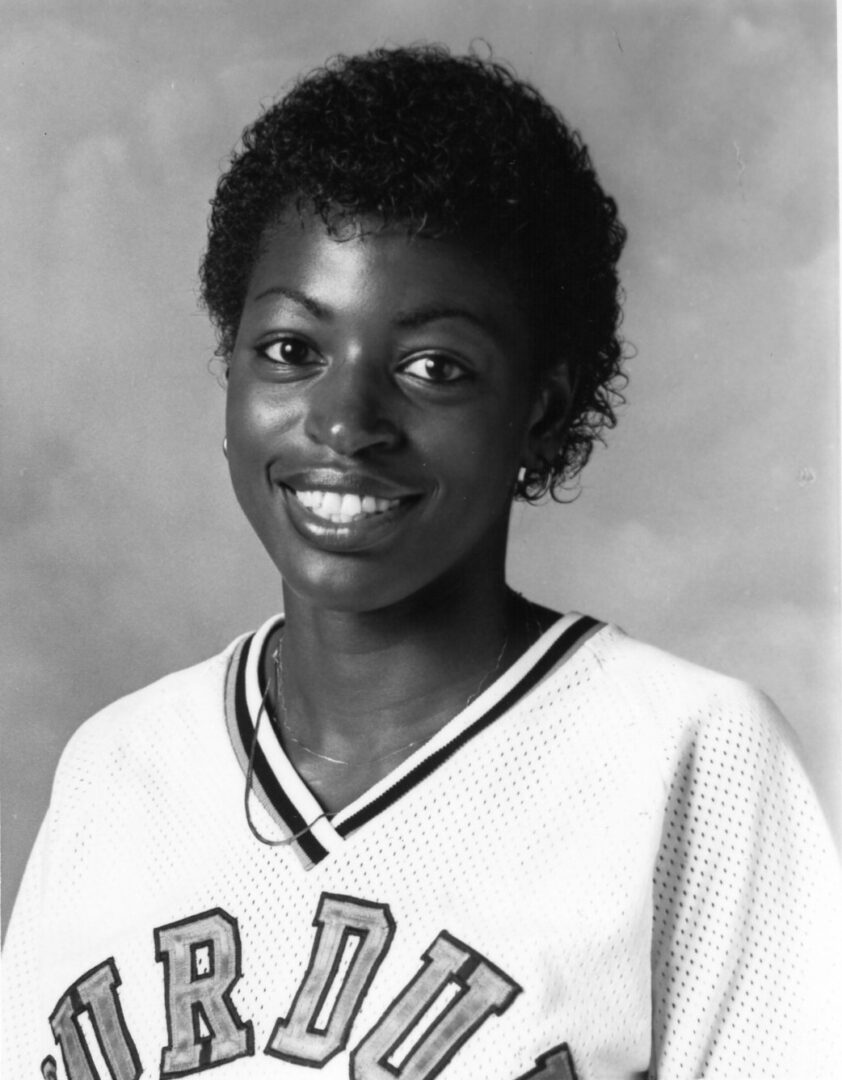

Pat Harris, women’s basketball, 1979-82

The study of Black history has to be more than one month. My message to kids is: ‘Learn how we got here and volunteer.’

Pat Harris

Purdue women’s basketball (1979-82)

With a reputation for calling it as she sees it, Harris is happy to embrace her trailblazer status in the history of the Boilermaker women’s basketball program. She admits she was as much a pioneer in women’s sports as a Black athlete at Purdue.

“Because women’s basketball was still in its infancy when I came to Purdue (it began officially in 1975-76), I guess you can call me a pioneer,” Harris says. “Women’s sports weren’t embraced by the athletic administration at the time.

“Years after graduating, I remained involved with Purdue Athletics because athletics director Morgan Burke embraced the growth of women’s sports, in part with his advisory council, which I was proud to serve on. He brought Purdue into the 20th century. So my challenge was as much being a female athlete as it was being one of the first Black basketball players at Purdue.

“I credit our head coach, Ruth Jones, and assistant, Nancy Cross, who also coached field hockey at Purdue, for moving things forward to build the foundation for women’s basketball and women’s sports at Purdue.”

Harris was raised in a traditional Black home with hard-working parents, but like Parrish, attended a predominantly white high school in Columbus, Ohio. Yet, she embraces the necessity of teaching Black history. Not just to Black kids, but everyone.

“Black History Month is very important as kids aren’t taught it as much as they should be. I worry that today we are in a tenuous political time, and we are taking some steps backward as a society when it comes to race relations and understanding one another. The study of Black history has to be more than one month. My message to kids is: ‘Learn how we got here and volunteer.’”

Harris practices what she preaches. She freely gives of her time in Indianapolis, her home for the past 40 years, while continuing various roles in administration and business. A long-time women’s basketball season ticket holder, Harris frequently makes the trip up I-65 from Indianapolis and is forever connected to the university.

“I had a very good experience at Purdue,” Harris says. “My mentors were my parents, who raised me in an environment where I was not given many extra things but was encouraged to take advantage of opportunities. So, I did. I took full advantage.”

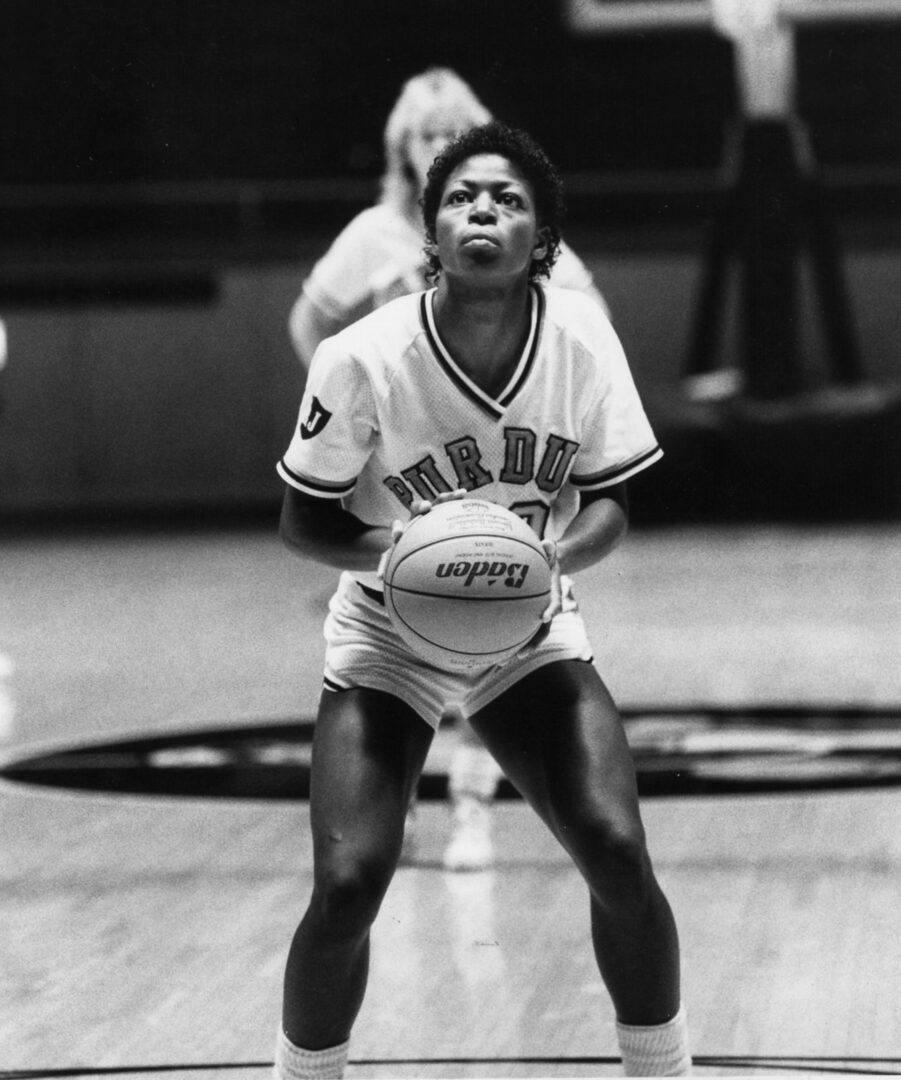

Cathey Tyree-Smith, women’s basketball and track & field, 1984-87

In a word, Tyree-Smith had a “happy” experience during her days as a Boilermaker from 1984-87. It didn’t hurt that she was one of the most talented dual-sport athletes in Purdue history.

“I loved my playing and competition days at Purdue,” Tyree says from her home in Deming, New Mexico.

A native of Fort Wayne, Indiana. Tyree-Smith was selected Purdue’s Female Athlete of the Year and the team MVP for both basketball and track & field in 1987. In track, Tyree-Smith was a three-time All-American and Drake Relays champion in the heptathlon.

She also was the Big Ten record-holder in the heptathlon, a record she held when she was one of the earliest inductees into the Purdue Athletics Hall of Fame 26 years ago. Tyree was a three-time honorable mention All-Big Ten selection on the basketball court, averaging 10.8 points and 7.4 rebounds during her four-year career.

“I always felt welcome and comfortable at Purdue,” Tyree-Smith says. “When I was recruited, Coach (Ruth) Jones was the only one who would let me play two sports, which made choosing Purdue easy.

“Purdue was intimidating, but not because of race. It was intimidating because it was such a big university and a big place. Growing up where I did, nothing ever bothered me. I was always around people with whom I could easily blend in. I never had controversy regarding race or anything like that. It was hard to go through Coach Jones getting sick and having several coaches, but our team stuck together.”

One of the first six freshmen to earn full scholarships in women’s basketball, Tyree-Smith always remains grateful.

What is the message of Black History Month from Tyree-Smith’s perspective?

“Going to Purdue for any person of color is very prestigious,” Tyree-Smith says. “I learned to keep my head level through everything. I realized that others before me didn’t have the opportunities I did, and I appreciate those who came before me.”

Written by: Alan Karpick, akarpick@goldandblack.com