Amelia Earhart: Aviator. Legend. Boilermaker.

Portrait of Amelia Earhart wearing flying helmet and jacket, 1922; same photo used in Earhart’s 1923 pilot’s license, issued by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale and National Aeronautics Association of U.S.A. Inc. Unless otherwise indicated, all photos are from Purdue University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections, George Palmer Putnam Collection of Amelia Earhart Papers and the Amelia Earhart at Purdue collection.

One of the most famous aviators of all time, Amelia Earhart worked at Purdue from 1935 until her disappearance in 1937

Editor’s note: Purdue University, Purdue Research Foundation (PRF) and the Archaeological Legacy Institute (ALI) announced Monday (Oct. 27) that the Taraia Object Expedition, a joint mission to locate Amelia Earhart’s lost aircraft in a lagoon of Nikumaroro Island, has been postponed to 2026. The decision comes as the team awaits additional clearance from the Kiribati government and as seasonal weather challenges kick in over the Pacific Ocean during winter months.

In 1935, Amelia Earhart was at the height of her celebrity. She had a record-setting solo flight across the Atlantic. She was a published author, a designer of her own fashion line, a charter member of the Ninety-Nines and an outspoken advocate for women.

What, then, inspired one of the most famous people in the world to live in West Lafayette and work for Purdue University?

An irresistible opportunity and a charismatic university president.

Right person, right place, right time

Purdue President Edward Elliott led the university with an eye always looking toward the next giant leap. During his 23-year tenure (1922-45), enrollment more than doubled, 28 major buildings — including an airport— were constructed and the university’s net worth nearly tripled.

Elliott hired Dorothy Stratton in 1933 as the first full-time dean of women students. Construction was complete on Purdue’s first women’s residence hall. And a record 800 undergraduate women were attending the university.

Unfortunately, a number of these women didn’t stay to complete their degrees. And those who did earn a diploma often gave up their careers to get married and start a family.

“Elliott was concerned,” says John Norberg, historian and author of Wings of Their Dreams: Purdue in Flight. “He wondered why Purdue was charging women tuition and spending time and money educating them if they weren’t going to have careers. Something needed to change.”

Enter Amelia Earhart.

Elliott and Earhart first crossed paths in September 1934, when she addressed the fourth annual “Women and the Changing World” conference, sponsored by the New York Herald Tribune. Elliott was at the same conference, speaking on “New Frontiers for Youth.”

Earhart’s impassioned speech on aviation and the role of women in its advancement sparked an idea in Elliott.

He approached her with a compelling offer: Come to Purdue, where women are allowed to enroll in STEM disciplines. Inspire these young women to complete their educations and pursue meaningful careers.

Earhart said yes.

Elliott and Earhart quickly devised a plan that worked around the aviator’s busy schedule. For a few weeks each semester, she would live in the new women’s residence hall (now known as Duhme Hall), serve as a counselor on careers for women, advise Purdue’s aeronautical engineering department and enjoy access to the resources of Purdue’s new airport — the only one, at that time, at a U.S. college or university.

Earhart fulfilled these roles at Purdue from 1935 until her disappearance in 1937.

Inspiring young women

Earhart’s inaugural on-campus event was as keynote speaker for Purdue’s first annual “Conference on Women’s Work and Opportunities,” held Nov. 26, 1935.

As in so many avenues of her life, Earhart instigated progress in her role at Purdue.

“She has said she was the first woman in the country to hold the position of career counselor for women at a university,” Norberg says.

She was wildly popular with students. Norberg notes that her dynamism and excitement were contagious, and her interest in helping women was sincere.

“She would have 20 young women gathered to speak with her, and she would sit down on the floor with them and just talk,” he says. “As a reporter in the 1970s, I had the opportunity to interview some of these women, and they all said that the experience changed their lives.”

Earhart was also scientific in her approach to career counseling. She wrote a multipage questionnaire in which she asked women to reflect on work, both in and out of the home.

“She encouraged women to think about the kinds of jobs they were actually interested in, not just what they ‘should’ do,” says Katey Watson, the France A. Córdova Archivist in Purdue University Archives and Special Collections.

“She wanted them to think outside the box when it came to their careers,” Watson says.

She would have 20 young women gathered to speak with her, and she would sit down on the floor with them and just talk. As a reporter in the 1970s, I had the opportunity to interview some of these women, and they all said that the experience changed their lives.

John Norberg, historian and author of “Wings of Their Dreams: Purdue in Flight”

The ‘Flying Laboratory’

As a consultant in aeronautics, Earhart spoke with groups of engineering students, participated in aeronautical conferences on campus and advised Purdue faculty on their work.

But she was already looking ahead to what she could accomplish next.

“Earhart had this idea of flying around the world at the equator,” Norberg says. “Others had flown around the world, but no one had done it at the equator, which would have set a record for the furthest-distance flight.”

She outlined her plans for an around-the-world flight to Elliott and spoke of her desire to conduct research on how long-distance flying affected pilots.

Norberg says Elliott’s response was, “Well, we can help you with that.”

The newly formed Purdue Research Foundation established the Amelia Earhart Fund for Aeronautical Research to support Earhart’s trip and her research plans.

Purdue trustee and benefactor David Ross gave money, and further donations were received from J.K. Lilly; Vincent Bendix; and the Western Electric, Goodrich and Goodyear companies.

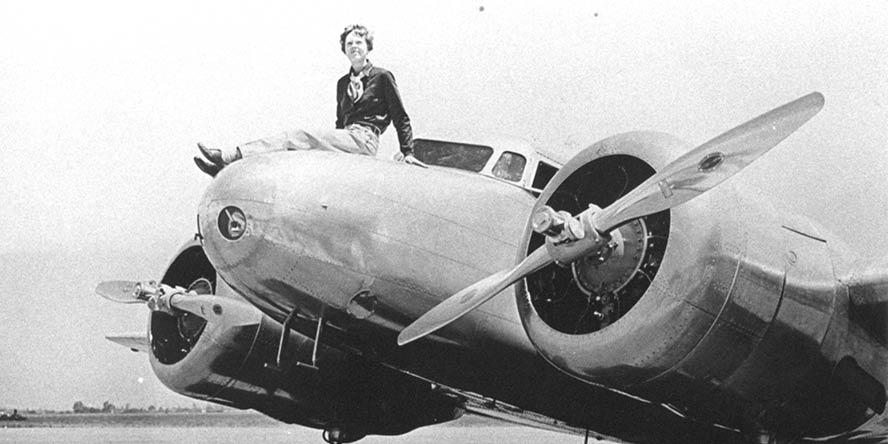

In 1936, Earhart acquired a Lockheed Electra 10E airplane specifically outfitted for long-distance flights, using just over $40,000 provided by the fund. It was called the “Flying Laboratory” because of new technological advancements that had been made in the field of aviation, including radio-telephone systems, newer navigational equipment and mechanisms that de-iced plane wings.

Earhart’s post-flight plan was to return the plane to Purdue, where it would be used to further pure and applied scientific research in aeronautics.

Purdue Airport

Readying for the world flight was a massive undertaking. And Purdue’s airport played a key role in Earhart’s preparation for her final, and perhaps most famous, flight.

“Purdue’s airport was the base for her world-flight research,” says Watson.

“She regularly flew out of the Purdue airport and could often be seen in the skies above campus as she prepared for her round-the-world flight,” Norberg says.

As Earhart readied for her journey, the eyes of the world were on West Lafayette.

“Having Amelia Earhart plan her flight here drew attention to Purdue’s airport and aeronautics program. She attracted incredible publicity for the university,” Norberg says.

Having the new terminal named for her means that she will continue to inspire women pilots, which was important to her. There are a lot of people who likely wouldn’t be pilots today if it wasn’t for her being vocal about the fact that women could fly and should fly.

Sammie Morris

University archivist

Purdue’s airport, which opened in 1930, was named a historical site by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in 2005. Earhart’s key role in Purdue’s aviation history was an important factor in this distinction.

Fittingly, Purdue University Airport’s new terminal will be named for Earhart when commercial flight service returns in spring 2024.

“One of the things I’m excited about with the naming of the new terminal is that Earhart had two passionate causes: aviation and women’s rights,” says Sammie Morris, professor, head of Purdue Archives and Special Collections, and director, Virginia Kelly Karnes Research Center.

“Having the new terminal named for her means that she will continue to inspire women pilots, which was important to her. There are a lot of people who likely wouldn’t be pilots today if it wasn’t for her being vocal about the fact that women could fly and should fly,” she adds.

World’s largest collection of Earhart artifacts

Earhart’s legacy persists at Purdue.

The university is home to the world’s largest compilation of Earhart-related papers, memorabilia and artifacts.

“We have nearly 5,000 items in the collection,” Morris says. “Original documents that belonged to her, along with many of her medals and awards. We have some of her clothing, her goggles, her pilot’s license, even her will.”

“We have the actual leather flight helmet and brown suede jacket she wore on her 1932 solo Atlantic flight,” Watson says.

“And of course, there are many photographs, telegrams, letters and other papers,” Morris says. “So it’s a really rich collection, and it documents her professional career, her time at Purdue and her personal life as well.”

The public can explore highlights of the collection or take a deep dive into the incredible complete collection online.

“There is one item that takes my breath away,” Morris says. “It’s this little flight log that Earhart kept during her solo flight across the Atlantic in 1932.

“It was the first time for a woman to make a nonstop flight across the Atlantic, and it was only the second time for a human. And all these things kept going wrong on the plane. She couldn’t tell how high or low she was flying; she had gasoline running down her shoulder and was afraid the plane was going to catch on fire,” Morris says.

“So she’s writing in this tiny little flight log about how if anyone finds the wreckage from this plane, please know that this is what happened. It was important to her while she was flying in these dangerous conditions to say, ‘I almost made it, and here’s why I didn’t,’” Morris explains.

“It just really puts you at that moment in history. It’s such a powerful connection to her,” she adds.

Origin and current use of the collection

The bulk of the Amelia Earhart collection came to Purdue in 1940.

“Amelia’s husband, George Palmer Putnam, was grateful to Purdue for the university’s support,” Morris says. “And after she disappeared, he offered her collection to the university, and President Elliott accepted it.”

In 2002, Purdue received an additional 492 items from Sally Putnam Chapman, the granddaughter of George Putnam.

“My grandfather chose to give the collection to Purdue because Amelia loved Purdue and because of Purdue’s generous sponsorship of her flights,” Chapman said.

Through the end of April, Purdue Archives is hosting an exhibit titled “Amelia Earhart: Life and Legacy,” which “explores not just her flying accomplishments, but her life,” says Watson, who curated the exhibit.

According to Morris, the Earhart collection is “heavily used, not only by people writing biographies about Amelia Earhart, but people writing journal articles about her role as a feminist or her impact on fashion.

“Students at Purdue use the collection. And I find it rewarding that elementary school students use it as well. They go on to the website and look at the collection, and then they will often contact us because they’re writing an Indiana history day report,” Morris says.

Watson says that student use of the collection is varied: “It’s across disciplines. Students might have a project on creating an original artwork, and they’re using collection materials to inspire their artwork. They could be doing research into flight history or on women and the gender revolution.”

From the public? “I have seen an uptick in children’s books,” she adds.

Legacy at Purdue

There are reminders of Earhart everywhere at Purdue. A statue of her stands outside the residence hall that bears her name. There is an Amelia Earhart Scholarship, an Amelia Earhart Faculty-in-Residence program and an annual Amelia Earhart Summit sponsored by the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Purdue Women in Aerospace.

Her most significant contribution, however, can be seen in the lives of Purdue students who are inspired by her example to pursue their dreams and aspire to careers that reward and challenge them.