Boilermaker in ‘beast mode’

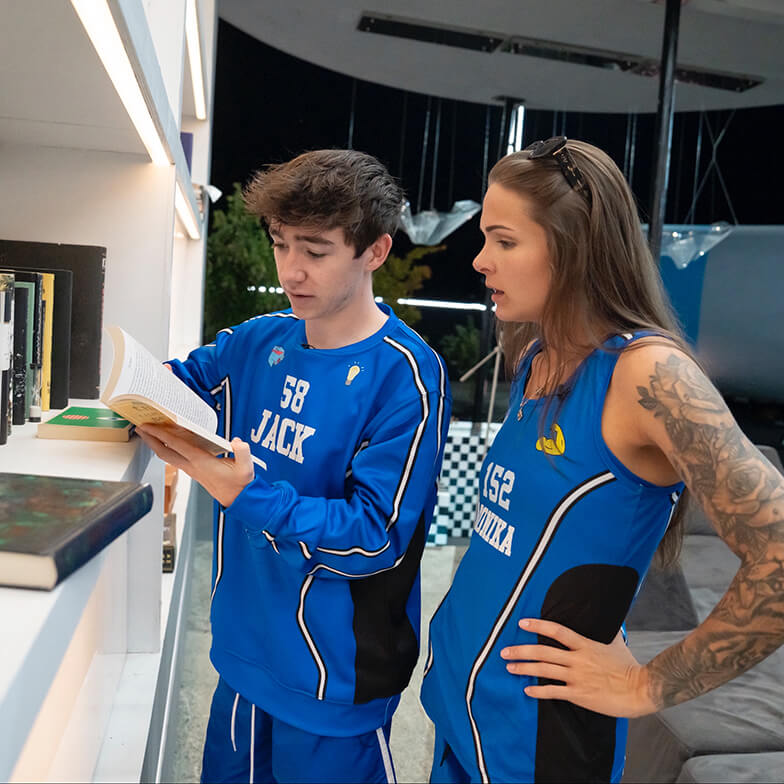

Jack McKenna competes on ‘Beast Games’ with MrBeast

John “Jack” McKenna is used to pressure. As an electrical and computer engineering junior at Purdue — and a contestant on the Prime Video reality show “Beast Games” — he knows that high stakes, long nights and relentless challenges are giving him the ride of his life.

At only 19 (he’s 20 now) McKenna was chosen from 400,000 applicants to be among 200 contestants on the second season of “Beast Games,” airing Wednesdays until Feb. 25. Though filming ended in the summer of 2025, his fate is a well-guarded secret. In advance of the next episode that will drop at Prime Video on Wednesday, Feb. 4, McKenna, given the moniker “child genius” for his youth and smarts, is one of just 11 remaining contestants.

Just back from a quick promotional trip to New York City, McKenna answered some questions from his room at the Sigma Nu fraternity house.

Q: What questions do you get most about your experience on the show?

A: I get constant questions — “How much money did you make? Who did you meet? How far did you go?” — and I’m dying to tell them, but I can’t. I went the entire fall semester without anyone knowing I was on the show. I told people I was doing a medical research study.

Q: How does the show keep a lid on things with hundreds of contestants?

A: They don’t call it “Beast Games” in any of the emails once you get cast, they call it “summer camp.” So, my emergency contact — my parents — would get texts every day during the show’s filming, saying, “Your camper is still at summer camp. They’re alive, they’re well, and we’ll give you another update in a few days.”

Q: You were filming for over a month. What was it like being there for so long?

A: You don’t have access to the outside world — no phone, no contact, no idea what day or time it is. This is your entire world. You spend every waking moment with the same people. The relationships you build in two weeks can rival relationships that take years in real life. It’s like being in a tiny simulation. You don’t see much production — it’s just you and the other contestants.

Q: What did you learn about yourself through this experience?

A: Perseverance. I faced moments on the show that felt devastating — like failing a final, times a thousand. But you learn it’s not the end. You regroup; you come back stronger. That mindset applies directly to engineering. You’re not always going to ace every exam, but what matters is how you respond.

Q: What made the experience ultimately rewarding for you?

A: Just being there. Over 400,000 people applied and only 200 made it. To experience something like that at my age — to test myself physically, mentally and socially — is something I’ll never take for granted. It was intense, exhausting and unforgettable.

Q: Doing the show took a lot of courage. Has it changed how you view bravery?

A: Honestly, applying for the show was the bravest part. Putting yourself out there — being authentic on camera — is scary. But I didn’t want to look back and feel like I wasn’t myself. Purdue helped me build that confidence. I wouldn’t have been the same person on that show without what I’ve learned here.

When it comes to academics, McKenna earned his ‘beast card’ long ago

McKenna’s dream is to work in the aerospace industry, a dream that began in his childhood and flourished as he excelled in school. In high school, he was among the highest academic achievers, even getting accepted to Mensa at age 15. So, majoring in electrical and computer engineering at Purdue is keeping his dream alive and on track.

Q: “Beast Games” put you under huge pressure. Did Purdue help you with that?

A: Purdue engineering is intense — and that’s a good thing. You go through long nights, difficult projects and stressful exams. You learn how to handle stress because it’s guaranteed here. On the show, with millions of dollars on the line, people cracked under pressure. I kept thinking, “This isn’t the most stressful thing I’ve ever done.” Finals week prepared me for that.

Q: Teamwork plays a huge role both in engineering and in the game. How did that translate?

A: You can’t win “Beast Games” alone. Purdue (engineering) really emphasizes teamwork — learning how to rely on others and how to be reliable yourself. I went into the competition knowing that alliances and trust mattered. Everyone has weaknesses. If you find a team that complements yours — and you do the same for them — you become really hard to stop.

Q: You had options when choosing a college. Why Purdue?

A: Academics were the biggest driver. I’ve always pushed myself to be at the top of my class, and Purdue kept coming up again and again as a place that would challenge me. Everyone I talked to who had gone to Purdue — alumni, family and friends — spoke incredibly highly of the education and the experience. They didn’t just talk about classes. They talked about basketball games, campus traditions and friendships. That stuck with me.

Q: Has Purdue lived up to that reputation?

A: It’s exceeded it. These have been three of the most transformative years of my life. I came in quieter, more reserved. Purdue pushed me out of my shell. The people, the classes, the campus atmosphere — it’s been everything I hoped for and more. I honestly wish I could start over as a freshman again.

Q: How key is Purdue to who you are today?

A: Being a Boilermaker is a huge part of my identity. Boilermaker grit is real. The lessons I’ve learned at Purdue are ingrained in me. I truly don’t think I would’ve performed the same way on “Beast Games” without Purdue shaping me first.

Boilermakers share dream of shaping America’s nuclear future

No one in this high-tech world should live without a consistent flow of electric power to their homes.

However, that’s hardly the reality for millions of people across the globe. And it could become a nightmarish predicament even in the U.S. if new solutions to meet the exploding demand for electricity aren’t explored quickly enough.

Recent Purdue alum Ryan Hogg (MS nuclear engineering ’25) experienced firsthand the issues that an unreliable energy grid can create while on a family trip to visit his grandparents in Johannesburg during high school. Rolling blackouts created all sorts of inconveniences that changed how the family approached home life, whether it meant timing showers for when they’d have access to hot water or reducing the number of times they opened the refrigerator to prevent its contents from spoiling.

“You noticed things that you had never noticed before,” says Hogg, a U.S. Navy pilot who has observed similar issues with inconsistent power on other international trips.

It motivated Hogg to contribute to the re-emergence of an existing, but perhaps not fully tapped, power source — nuclear energy — that has the potential to satisfy the world’s growing needs. That motivation brought the 2024 U.S. Naval Academy graduate to Purdue, where a cooperative effort between the Navy and the Purdue Military Research Institute helped him complete a master’s degree in nuclear engineering in 18 months and then return to full-time military service.

His background as a nuclear engineer makes him something of a unicorn among Navy pilots.

“I might be the only one,” he says with a laugh. “I’m the only one I’ve ever met.”

‘I don’t think I could do this anywhere else’

Like Hogg, Purdue PhD student Hannah Pike (BS aeronautical and astronautical engineering ’23, MS nuclear engineering ’25) dreams of influencing the future of nuclear engineering — only she plans to go about it in a very different way.

A former captain of the World’s Largest Drum crew in the Purdue “All-American” Marching Band, Pike plans to become a college professor and continue her research that examines integrating AI and machine learning into nuclear operations.

Pike joined a research project with Purdue’s SCALE program during her junior year that convinced her to pursue a future in nuclear engineering. As a graduate student, opportunities to serve as a teaching assistant and as a research mentor for SCALE convinced her that this future would involve research and training the next generation of nuclear engineers.

Her research, which uses AI and machine learning to gauge radiation levels throughout nuclear facilities, has the potential to improve nuclear safety while taking measurements that humans can’t take.

“As I started working on my project, I became very interested in the topic, and I don’t think I could have this experience anywhere else,” Pike says. “Just thinking about where that research is going to go is very exciting.”

The interdisciplinary nature of nuclear engineering is another aspect of the field that appeals to Pike, who came to Purdue planning to someday become a NASA engineer.

“My interest in nuclear started when I learned about nuclear propulsion and potentially using nuclear energy to power rockets or something further down the line,” she says. “But then I learned that it also applies to agricultural engineering, has strong ties for electrical engineering and even mechanical. It just kind of interested me how it could relate to so many different disciplines. I could tell that nuclear engineering was one of those degrees where you could really make a big impact in a lot of different ways.”

I don’t think I could have this experience anywhere else. Just thinking about where that research is going to go is very exciting.

Hannah Pike

Nuclear engineering doctoral student, on her research that investigates AI and machine learning applications in nuclear reactor operations

Purdue’s unique features

There are many reasons why Hogg and Pike elected to pursue graduate studies in Purdue’s highly ranked nuclear engineering program.

They view nuclear facilities — particularly small modular reactors (SMRs), which are smaller, easier to build and less expensive than traditional nuclear power plants — as the obvious choice to meet America’s energy needs. And they have benefited from Purdue’s unique portfolio and focus on this emerging technology that continues to evolve.

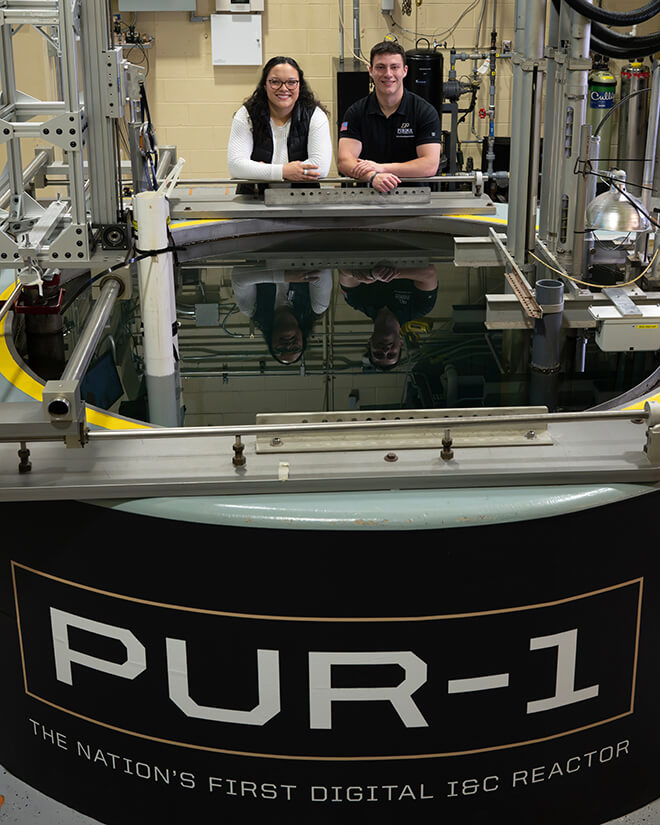

The university comes equipped with essential facilities to create solutions and meet the demand for a nuclear workforce that will need to nearly quadruple in size by 2050, according to U.S. Department of Energy projections. Those facilities include PUR-1, the nation’s only all-digital nuclear reactor, and the Purdue University Multidimensional Integral Test Assembly facility, which is being revitalized for SMR research, education and training.

PUR-1 is the only nuclear reactor in Indiana, and its digital controls and operations enable research that is not possible anywhere else in the U.S. And because of its limited capacity — it generates power equivalent to that of approximately 10 microwaves — Boilermaker students can gain useful hands-on experience in a relatively low-stakes environment.

“Coming from a school, at Navy, where we didn’t have that research nuclear reactor readily available for education, maybe I have a different appreciation for it than the people at Purdue who have always had it,” says Hogg, who completed a mechanical engineering degree at the Naval Academy. “Now it’s not just, ‘OK, the teacher told me I was right, so I know my chart is right and my graph is right.’ Now I can see it in real life and say, ‘We were close, but were we close enough for what real life should be?’ We’re making assumptions all the time, but it’s hard to prove those assumptions until we actually see it in person.”

Influencing the future

While the Boilermaker engineers have grand visions about how they can contribute to the nation’s nuclear future, they will not have to wait for some far-off date to make a significant impact within their chosen field. They’ve already done it, having contributed to an influential Purdue-led study that proposed using SMR technology to meet Indiana’s spiking energy needs and drive economic activity.

Hogg, Pike and fellow grad student William Richards were among the collaborators who visited the Indiana Statehouse to hear legislators deliberate on how to effectively add nuclear to the state’s energy portfolio, and they were unanimously thrilled by what they heard.

“It was very exciting to see that something I did was reaching out to so many different people, and they were actually using it to form opinions and viewpoints on nuclear issues,” Pike says. “Those who referenced our report really did use it to justify how right now is the time for nuclear to come to Indiana because it is the future of energy.”

The process is only beginning, however.

Hogg points out that an increased emphasis on nuclear power will introduce an array of regulatory, logistical, geopolitical and safety complications that will not be easy to solve. And yet he remains motivated to ensure that energy challenges will not prevent the U.S. from enjoying a bright, tech-driven future.

“Having that power would increase productivity as a whole for society,” Hogg says. “But to stifle it so early and then to change our minds later and say, ‘We actually do need power,’ it would be more than five years before we can get it up and running. I think that’s why we need advocates now: to prevent future issues from arising.”

Having that power would increase productivity as a whole for society. But to stifle it so early and then to change our minds later and say, ‘We actually do need power,’ it would be more than five years before we can get it up and running. I think that’s why we need advocates now: to prevent future issues from arising.”

Ryan Hogg

MS nuclear engineering ’25

Purdue’s senior stalwarts aim for the mountaintop

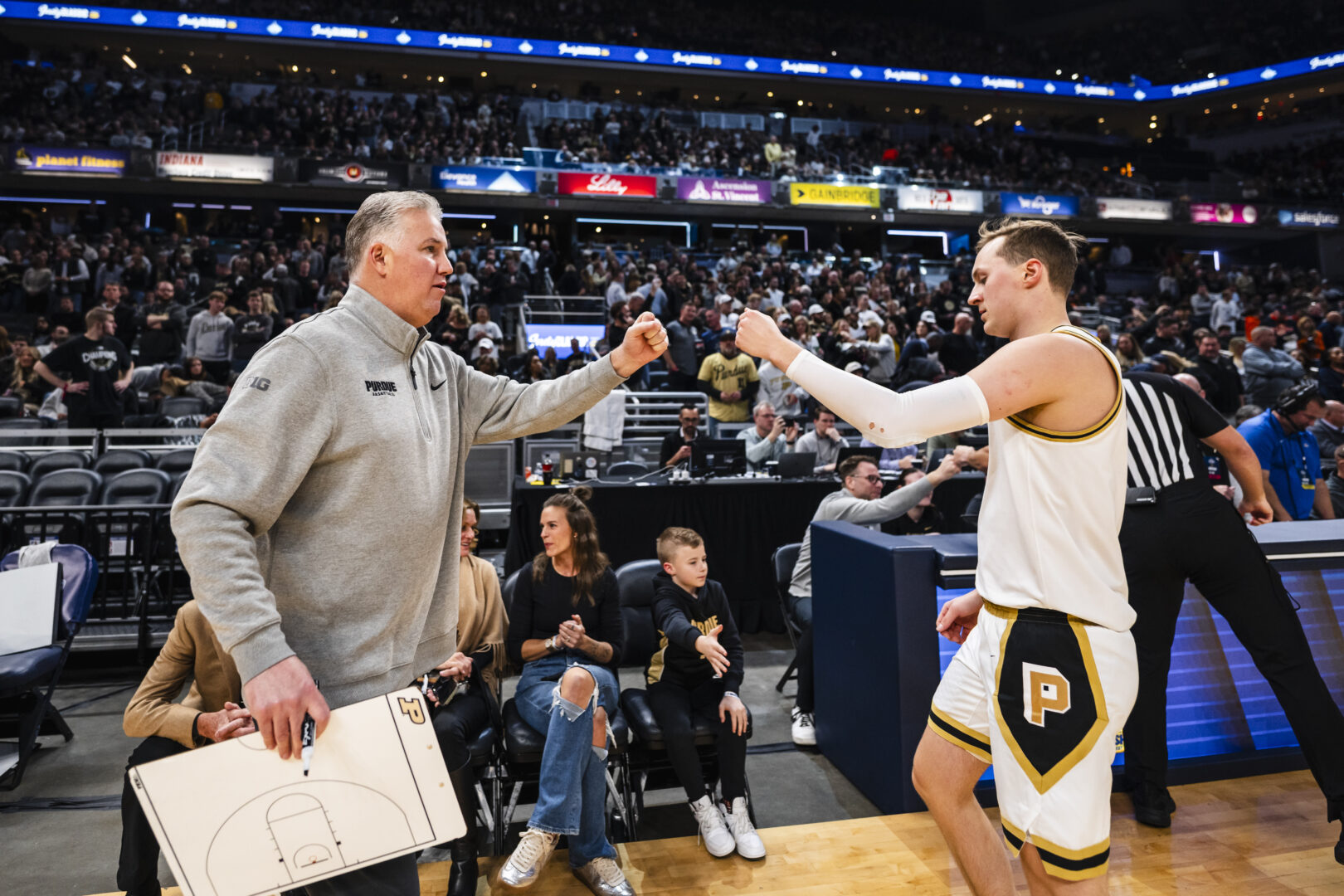

Top-ranked Purdue had just taken care of business against overmatched Rutgers at the start of December, and the local media — the New Jersey media — was buzzing immediately afterward, waiting for the visiting coach to arrive at the postgame press conference.

Such is Matt Painter’s standing these days as a leading voice in college basketball that he and Michigan State’s Tom Izzo now share the unofficial titles of faces and voices of the Big Ten. So when either comes to town, local writers rely on them to contextualize whatever circumstances the home team is experiencing.

In this case, a prominent Jersey columnist based out of Asbury Park needs a diagnostic from Painter on Rutgers’ struggles this season, as coach Steve Pikiell’s program rebuilds with freshmen. So far, it has not been particularly smooth.

The question prompts a Painter symposium on modern program-building as transfer culture and player compensation considerations loom over recruiting, roster construction and retention.

“It works if you can keep ’em,” Painter says before espousing the virtues of building with “company men” who will stay in one place and prioritize winning and other substantive considerations over most else.

“He just wrote my column for me,” the columnist half-joked to no one in particular as soon as Painter stood to leave.

But Purdue’s coach wasn’t just shining a light on Rutgers’ plight for the locals. By comparison, he was telling the story of his own team’s ascension. The preseason No. 1 Boilermakers are built around fourth-year players Braden Smith, Fletcher Loyer and Trey Kaufman-Renn, arguably the best trio in the sport, but also a rare foundation of not only ability and achievement, but continuity and experience that could take the Boilermakers a long way this season.

College basketball’s outliers

It didn’t used to be this way, but Purdue’s ability to keep this core together makes it something of an outlier in college basketball these days.

Painter has no aversion to supplementing his roster with transfers, as evidenced by recent additions like Oscar Cluff and Lance Jones. But Painter is not going to recruit a whole new team every season, as most of his peers seem to do, either by choice or due to their circumstances.

The results speak for themselves.

With this promising season’s outcome still to be determined, Smith and Loyer have started every game of their college careers and played leading roles in 97 wins entering the Dec. 20 game against Auburn. Kaufman-Renn has played a part in all of those wins but two, missing just the first two games of 2025-26 against Evansville and Oakland.

Together, the trio has helped Purdue to its first Final Four in nearly a half-century and won two Big Ten regular-season titles and one conference tournament title. They have been part of three No. 1-ranked teams.

When all is said and done, their names will long stand among legends throughout Purdue’s record books. They will almost certainly have accomplished more than any class ever at a school that takes basketball very seriously, in a state that takes basketball very seriously.

“We have a single motivation now,” says Kaufman-Renn, a preseason All-American as a fifth-year senior. “I’ve said to those guys that I feel like we’ve done everything else. (A national championship) is what matters more than anything to us now.”

Achieving that goal certainly won’t be easy, but none of the three seniors signed up for easy when they chose Purdue during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The seniors have seen it all

From the non-traditional nature of their recruitment to Smith and Loyer playing significant minutes as true freshmen, to Kaufman-Renn being the rare blue-chip recruit who excitedly redshirted as a freshman, then waited two seasons for a leading role, very little has come easy to this group.

It was hard when the three of them were part of a historic NCAA Tournament loss as freshmen, and hard when they joined Zach Edey in making a landmark run a season later, carrying the burden of redemption on their backs.

The undercurrent of their collective careers has made Purdue not so much an exception to a modern rule, but increasingly an outlier.

None of them ever had reason to leave Purdue. Still, any of them could have capitalized on the most tumultuous era of unabashed profiteering in the history of a sport that’s been driven by money for generations.

Purdue’s seniors have all done quite well for themselves as is, but Painter has made special mention of his entire team turning away more lucrative options to remain at Purdue.

“It’s just what Paint has built and it’s the type of people we are,” says Smith, the Big Ten’s preseason player of the year and a popular name in the tampering community last spring. “We all have common goals. We all want to win.”

Painter sounds a bit too wholesome to be true sometimes when he talks about the importance of being open, honest and fair with players — not just during their careers, but in recruiting, so that no player or proxy can credibly feel misled. It has fostered an environment where mutual trust and loyalty are virtually tangible, in a competitive landscape where trust and loyalty are as likely to be punchlines as guiding principles.

Since Day 1 for Purdue’s three foundational seniors, they’ve enjoyed abnormally healthy, open and mutually beneficial relationships with their coaching staff, while many of the teams they’re competing against — not all, but many — are doing things transactionally, a few months at a time.

Purdue is rolling out a team led by fourth-year players — stars, no less — against teams led by four-month players.

It’s worked.

The chemistry these players display is unmistakable, noticeable when Smith races the ball up the floor, knowing the whole way exactly where Loyer is and where he needs to catch the ball to shoot the 3. (If Smith leaves Purdue with the NCAA’s all-time career assists record, those transition looks for Loyer will be every bit a part of it as anything thrown behind his back or 12 feet in the air for Edey to dunk).

The veterans’ synergy is apparent when Loyer runs off a baseline screen and throws a quick entry to Kaufman-Renn to the precise spot he will reach just as the ball arrives.

Actually doing something special

These players came in together, stayed together, grew together, struggled together, thrived together and found common cause together.

That’s where Purdue is different. Not one-of-one by any means, but not nearly as common as it was just a few years ago, when it was mostly the one-and-done NBA mills replacing players every few months.

It makes you feel like you’re actually doing something special and not just collecting NIL checks like a lot of these teams are. It feels like you’re really part of a team and working toward something that means a lot to not only you, but also to a whole university, a great coach like Coach Painter and a great fan base as we have here.

fletcher loyer senior guard

Indianapolis hosts this year’s Final Four.

“Obviously, winning the Big Ten, making the Final Four, those things are special and put us in the history books, but you want to end the season on a win, end the season in Indy, in front of our fans,” Loyer says. “When I committed here five or six years ago, Purdue was in a great spot, but it wasn’t at the mountaintop. If we can leave here having brought Purdue to two Final Fours and winning the Big Ten three out of four years, it would put Purdue at the peak of college basketball.”

And Painter would have done it his way, with company men.

It will have worked because he kept them.

Written by Brian Neubert, GoldandBlack.com

Purdue and Beck’s are reimagining the future of farming

Advanced agricultural research and a pipeline of highly skilled workforce talent drive innovative partnership

This story highlights one of the many ways Purdue teams up with corporate partners to create solutions for complex global challenges. Learn how your organization can collaborate with us.

Say the word “agriculture” and most people think fields and farmers, crops and plows. Most people don’t associate farming with machine learning, computational analysis and AI. But Beck’s does.

Beck’s is the largest family-owned retail seed company in the United States. Based in Atlanta, Indiana, Beck’s has always been on the leading edge of what’s next in their industry. The Beck family has invested 90 years in the seed business, and its connection to Purdue dates back even further.

The company places a strong emphasis on innovation and education. Through its partnership with Purdue, Beck’s has access to advanced agricultural research and a pipeline of highly skilled workforce talent.

Building ‘unicorns’

About six years ago, Brad Fruth (ASCT ’01) was tasked with creating the Beck’s innovation group. Early on, he saw the value of partnering with land-grant universities. As the director of innovation, his initial focus was on building a resilient talent pipeline.

“We wanted the best of the best,” he says. “And so we derisked recruitment for our company by building a bridge between Beck’s and Purdue. We brought the university projects, and we received access to top talent.”

Beck’s has strengthened its workforce development ecosystem even more by bringing an industry-transforming research project to Purdue.

“We were able to match a cutting-edge project with Purdue students who have skill sets that are not readily available out in the wild,” Fruth says. “And then we were able to say, ‘OK, now why don’t you join our organization?’ It allowed us to build our own unicorns rather than blanket hiring a disparate group of people and hoping that we got the right ones for our team.”

Venkata Limmada, a Purdue PhD student in agronomy, agrees. “Through this collaboration, Beck’s gains access to multidisciplinary student teams who are highly skilled in their respective fields. At the same time, the partnership helps build a pipeline of future talent who already have experience working with Beck’s data, tools, and organizational needs.”

Computational breeding

Beck’s high-impact research project with Purdue is a computational breeding platform. For decades, Beck’s has collected detailed information about corn crop varieties — their traits and the DNA sequences they hold. They have partnered with Purdue to translate these large datasets into smarter plant breeding and stronger crops.

One of the things that Fruth discovered in this collaboration is the value of having access to a cross-disciplinary team.

“Management students, ag students, computer science students, math students, data science students — having all of them coalesce on one project has been very meaningful for us,” he says. “There was not one single source we could go to from a consultancy standpoint to tackle this project.”

The computational breeding platform is no ordinary project either. It’s a high-stakes undertaking with the power to transform an entire industry. “We knew that the decisions we were going to make on this project are going to shape the next generation of our R&D pipeline,” Fruth says.

Seyi Ogunmodede, a PhD candidate in the School of Applied and Creative Computing, leads one of the interdisciplinary teams working on the Beck’s project. Ogunmodede and his Purdue colleagues created multiple predictive analytics models for plant breeding.

“Utilizing advanced analytics and machine learning tools like deep learning, time series clustering, embedding, transformer, genomics best linear unbiased prediction, convolutional neural networks and XGBoost, we are able to create models that help predict the strongest crop hybrids and which varieties will best suit the regions in which they are grown,” he says.

“The whole team works together in a way whereby we’ve been able to predict what will happen in the following season, in the following year and how farmers can gain a better yield.”

We are able to provide corporate partners with high-impact results backed by teams of trained researchers and student analysts.

Seyi Ogunmodede

PhD candidate, School of Applied and Creative Computing

The Data Mine

Ogunmodede’s work with Beck’s is facilitated through The Data Mine, an interdisciplinary living-learning community of Purdue students who work alongside corporate partners and Purdue faculty to provide solutions to today’s toughest challenges.

Ogunmodede points to the opportunity to collaborate across disciplines, handle large datasets and cocreate solutions with industry professionals as what makes partnering with The Data Mine transformative.

“As a team leader and graduate research assistant with The Data Mine, I have witnessed firsthand the significant benefits organizations gain from partnering with Purdue,” Ogunmodede says. “We are able to provide corporate partners with high-impact results backed by teams of trained researchers and student analysts.”

Fruth agrees. “The Data Mine was able to bring five different disciplines together on our project,” he says. “Working together to build something brand new helped us achieve our goals. We have other businesses asking us how we are being so successful.”

The best corn for next year’s crops

Lorena Ferreira Benfica, a postdoctoral researcher at Purdue who specializes in genomics, plays a key role in the university’s partnership with Beck’s. Among her responsibilities are receiving all raw genomic data, organizing and formatting these datasets, and performing quality control so the team can use them in the genomic prediction models.

“Beck’s has thousands upon thousands of options,” she says. “We help them transform large amounts of information into genomic predictions that guide breeding decisions and drive impact in the field.”

Access to innovative, data-driven solutions is only part of the Purdue x Beck’s equation. Fresh perspectives and cost-effective collaboration are others.

“The creativity, the innovation, that’s a key piece of what Purdue brings to the partnership with Beck’s,” Ogunmodede says. “And the students who work on this project, they are really energetic. They want to develop new things. They know about the latest technology, and they want to see it in action.”

Beck’s willingness to try new things is also a key component of the partnership. “They have such an open point of view and an eagerness to embrace new ideas and technology,” Ferreira Benfica says. “It’s been amazing to work with them.”

Industry, knock here

Partnerships like the one Purdue has with Beck’s create distinctive opportunities for companies to innovate. “When we were at a crossroad of not knowing how to technically solve a problem,” Fruth says, “that’s when we said, ‘I think we have a university that can help us with this.’”

Purdue’s guitar-building expertise draws ‘Monday Night Football’ spotlight

Mark French and his Purdue guitar lab team created a football-themed instrument for ESPN’s Colts-49ers pregame broadcast

After observing the excitement Purdue’s guitar lab generated by building the “Win for Jim” guitar for the Indianapolis Colts, ESPN decided it wanted a one-of-a-kind instrument of its own.

And the network knew the perfect time to show it off: during its pregame coverage for the “Monday Night Football” matchup between the San Francisco 49ers and the Colts — the team once owned by Jim Irsay, the late guitar collector who inspired the tribute guitar.

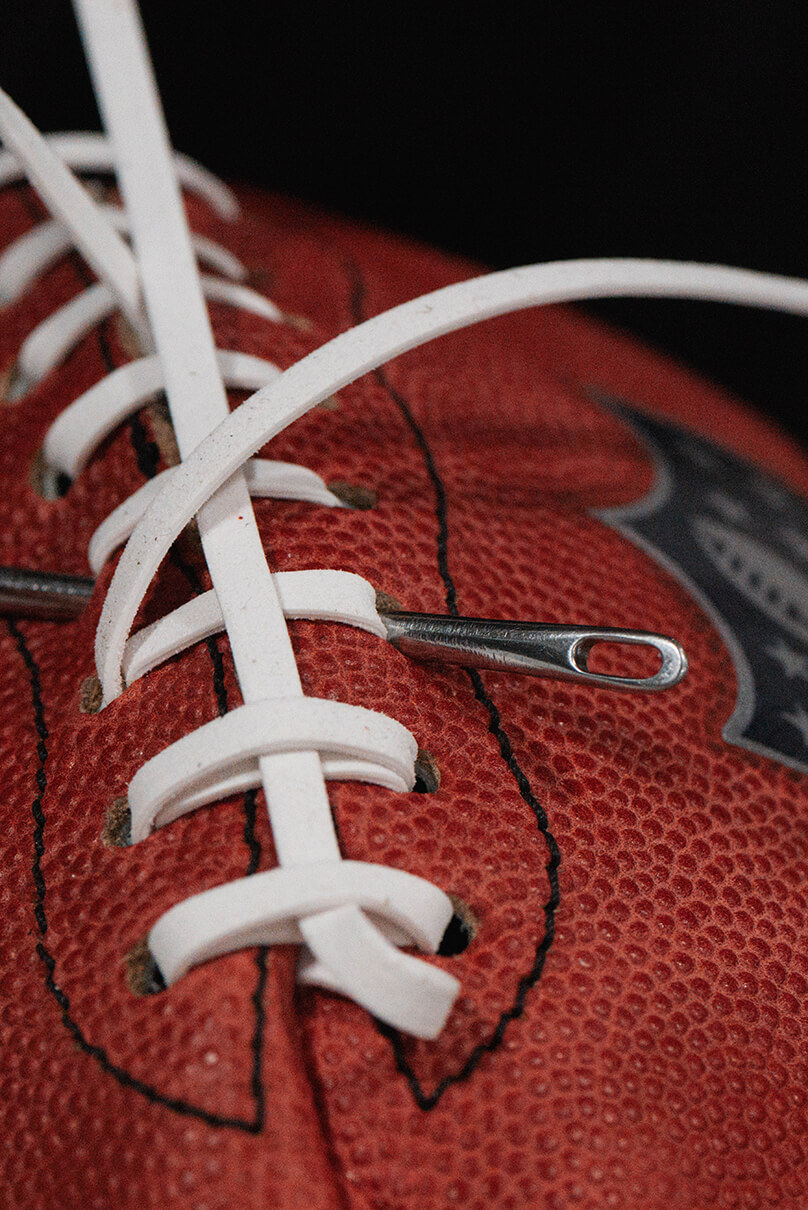

This time, the uniquely talented group of Boilermakers designed a custom electric guitar with a leather face resembling an NFL football — laces and all.

And not just any leather. The leather face sheet came directly from the Wilson Football Factory in Ada, Ohio, where Wilson Sporting Goods has been making NFL game balls since 1955.

The material was not the only unique aspect of the guitar face, however. The leather also received authentic game day treatment courtesy of the Purdue football equipment staff.

Follow along to see how the guitar-building process occurred before the instrument made its network debut:

Acquiring authentic NFL game-ball leather

After collaborating on the “Win for Jim” guitar prior to the season, Purdue guitar lab creator and mechanical engineering technology professor Mark French asked alumnus Noah Scott to once again take the lead on the project once ESPN reached out with its request.

Scott started by coordinating with ESPN on a design and reaching out to Wilson, seeking to acquire sheets of authentic NFL game-ball leather to use on the guitar face.

Fortunately, Wilson agreed to help, assigning recent Purdue engineering alum Parker Nordstrom to the project.

“It felt a bit like a movie where the script had things work out with just the right people and just in time,” says Scott (BS industrial engineering technology ’20, BS organizational leadership ’20, MS finance ’21). “Wilson thoughtfully assigned a young Purdue alum, Parker, who quickly stepped up to the plate, took creative ownership of Wilson’s end of the project, and stayed after hours most days to get the leather put together according to our design.”

Scott drove to Ohio to pick up the guitar leather at the Wilson facility, where Nordstrom and his colleagues showed him the steps they follow to produce 500,000 footballs each year — a process they mimicked in assembling the guitar leather, right up to the stitching and lacing they applied to the material.

“Once I realized we were trying to take materials and processes designed for a football and apply them to a guitar, it instantly felt like a big engineering puzzle,” says Nordstrom (BS mechanical engineering ’23, MS sports engineering ’24), a manufacturing/mechanical engineer at Wilson. “We were constantly asking, ‘How do we sew this panel so the seam lands in the right place? How do we lace it so it looks authentic but still lays flat on the guitar? How do we stamp it so the Motion P and foil stamps fall into the correct spot?’

“Working through those questions and testing different approaches was a blast,” he adds. “It’s the kind of challenge you don’t get very often — familiar materials, completely new application — and it pushed me to think differently about our normal processes.”

Nordstrom was uniquely qualified to take on this challenge, having been part of Purdue’s first full cohort in the sports engineering professional master’s program that began when Purdue launched the Ray Ewry Sports Engineering Center. Since that background helped Nordstrom launch a career in the sporting goods industry, he saw the guitar project as a way to return the favor.

“What made it even better was getting to do it alongside Purdue,” Nordstrom says. “Being able to support a project coming out of my alma mater, and specifically out of a space like the guitar lab, felt pretty full circle for me.”

Purdue football staff gives leather the game day treatment

Scott also asked the Purdue football staff to help ensure that the leather on the guitar face was as authentic as possible. So Kyle Gergely, the football program’s associate director of equipment, invited student manager Drew Decker to prepare a section of the leather as if he were breaking in a football to make it easier for the Boilermakers’ quarterbacks to grip during a game.

Allow Decker to break down Purdue’s standard ball-prep process:

- STAGE 1: “It starts with taking off the factory coating and dye with a brush, then we massage in shaving cream and let that sit for a while,” he says.

- STAGE 2: “Next, we do the same thing with the leather conditioner, then we rub a layer of mud all over the ball, which allows for the leather to turn a dark brown, which the majority of quarterbacks prefer.”

- STAGE 3: “Let the mud sit overnight and then brush the mud off with a hand brush.”

- AND FINALLY: “Once we get the mud off, we add another layer of leather conditioner, which helps bring out a nice shine.”

The ball-prep process takes more than a day to complete, but Decker was excited to tackle the unique assignment.

“I know how much guitars have meant for the Colts this season and how much they meant to Jim Irsay, so being able to be a part of something with this magnitude is pretty special,” says Decker, who is majoring in construction management when not working with the Boilermaker football team.

Building a guitar worthy of the ‘MNF’ spotlight

Using such an unusual material on the guitar face made it a stressful four-day assembly process for guitar lab professor French, who had never bonded leather to the wooden body of a guitar.

“I don’t know if anyone has ever done this before, so I’m on a voyage of discovery,” French says, noting that he leaned on the leatherworking expertise of Eric Martinez, a student in his guitar class.

The complicated process also involved preparing the body and neck, applying the “Monday Night Football” logo to the pickguard, trimming and refining the leather after curing, and making precise cuts to the material to allow for installation of the guitar’s hardware as they completed the assembly.

As was the case with the “Win for Jim” guitar, French viewed the ESPN project as a worthwhile endeavor to showcase what Boilermakers can do in the guitar lab, which relies on donations to operate.

“They both seemed like a good chance to show a larger audience what kinds of things happen at Purdue,” French says. “They also looked like opportunities to introduce people to the guitar lab. This is a unique place, and one that the students really value. It’s a great place for them to combine their classroom learning with the act of making a product they are really interested in.”

But it was a rushed process throughout due to the compressed timeline. Once the team completed the assembly, they still had to leave enough time for testing and for Scott to practice with the instrument before playing it alongside ESPN analyst Jason Kelce before the game.

“I’m less nervous about my performance — as I’m practiced enough to do it in my sleep — but more so nervous about representing the lab, its students and inherently Purdue as a whole, to a certain extent,” Scott said prior to his ESPN appearance. “The performance isn’t about me; I just happen to be the guy lucky enough to get the call.”

The science of ‘Stranger Things’: Purdue experts weigh in

Perhaps some of the Indiana-based sci-fi series’ subject matter is not so far-fetched after all

Millions of viewers remain spellbound by the fantastical events of “Stranger Things” — Netflix’s classic 1980s science fiction series whose final episode will arrive Dec. 31. Although the show is renowned for seemingly impossible action involving mind control, traveling to parallel dimensions and battling monsters, perhaps some of its subject matter may not be so fictional after all.

Here, Purdue experts weigh in on whether what we see on “Stranger Things” is possible — or could be someday — and the fear factor that has kept us binge-watching through the years.

Q: Could the brain ever control objects — or other people’s thoughts?

A: The human brain remains a profound mystery, yet innovative engineering is opening new doors. Low- to mid-bandwidth brain readouts allow for basic digital control via thought, but advances in high-bandwidth transmission from brain implants to wearables are now enabling richer, more complex interactions, as discussed in recent Nature Electronics research.

These leaps promise more meaningful ways to connect our minds with technology. As new possibilities emerge, society must amplify the benefits and thoughtfully shape boundaries to ensure the ethical use of these opportunities. For now, while direct machine control is real, controlling other minds remains firmly in the realm of science fiction.

— Shreyas Sen, Elmore Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering

For now, while direct machine control is real, controlling other minds remains firmly in the realm of science fiction.

Shreyas Sen

Elmore Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Q: Could electromagnetic energy ever open a gate between two worlds?

A: Electromagnetic energy can not — so far! — open a gate between worlds, but light waves tirelessly carry all your Zoom conversations and Netflix streaming across the world.

And remember, physics has not ruled out multiverses and quantum tunneling!

— Alexandra Boltasseva, Ron and Dotty Garvin Tonjes Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Q: Why do monsters feel real even when we know they’re not?

A: Even when we consciously know the monsters in “Stranger Things” aren’t real, our brains respond as if they are because fear circuits (e.g., the amygdala) are wired to detect and react to threat cues automatically, before rational thought can intervene.

Even when we consciously know the monsters in “Stranger Things” aren’t real, our brains respond as if they are because fear circuits (e.g., the amygdala) are wired to detect and react to threat cues automatically, before rational thought can intervene.

Hongmi Lee

Assistant professor, Department of Psychological Sciences

Immersive storytelling amplifies this effect. Engaging narratives draw us into the characters’ experiences, activating brain regions involved in memory and emotion. As a result, we don’t just watch the fear — we may feel it.

These emotional and physiological responses can linger after the show ends as our brains tend to replay the story, especially when it is particularly engaging and immersive (e.g., Bellana et al., 2022).

— Hongmi Lee, assistant professor, Department of Psychological Sciences

Purdue couple’s reindeer bring seasonal flair to holiday events

Ag alums Becca and Cadel Crowl launched Lafayette-based Indiana Reindeer Co. in 2023

Do reindeer live in Indiana? Believe it or not, the answer is yes — and they have been helping a Boilermaker couple bring a special brand of holiday cheer to Greater Lafayette since 2023.

Ever since Purdue agriculture alums Becca and Cadel Crowl founded Indiana Reindeer Co. that year, they have frequently brought pairs of their eight total reindeer to community holiday events to provide the perfect seasonal flair.

“Being able to experience the joy and excitement the reindeer bring everyone who meets them is one of our favorite things about having a reindeer farm,” says Becca Crowl, who adds that their reindeer happily attend approximately one event per day during the busy holiday season. “Cadel and I really love sharing the story of how the reindeer come to our farm from Alaska, as well as highlighting each of the reindeer’s personalities that we have with us that day.”

The animals live year-round at the Crowls’ Lafayette farm, benefiting from the proximity to expert care at Purdue’s College of Veterinary Medicine. Because they are happy and healthy here, the reindeer are able to make the holidays that much more enjoyable for those who encounter them during this special time of year.

Becca Crowl (BS agricultural systems management ’12), on her family’s eight reindeer like Denali, pictured above

Purdue and Elanco are partnering to unite human, animal and plant health

Two Indiana powerhouses partner to build the future of health — for all

This story highlights one of the many ways Purdue teams up with corporate partners to create solutions for complex global challenges. Learn how your organization can collaborate with us.

The air we breathe, the food we eat, the pets we love — all of it changes us.

Purdue scientists, in partnership with Elanco Animal Health, are uncovering how these invisible connections form the ecosystems we carry within us and define true health — not just for humans, but for every living thing.

This interconnected approach is called One Health: the idea that human, animal and plant health are deeply intertwined. In other words, the same forces shaping our own internal microbiomes are influencing livestock, crops and entire ecosystems across the world.

If you’ve ever wondered why seasonal allergies hit harder in one city than another or why growing up with pets affects your immune system, you’re already thinking like a One Health scientist.

But no single person — or institution — can trace all the ways our environments shape our health. Making sense of those connections takes partners who see health from different vantage points. That’s where Purdue and Elanco come together.

A shared vision for One Health

Through its One Health strategic initiative, Purdue is driving discovery and economic growth across four strengths: top-ranked academic programs, world-changing research, advanced facilities and powerful industry partnerships — including a transformative relationship with Elanco.

That momentum now expands into Indianapolis, where Purdue and Elanco are developing the One Health Innovation District, anchored by Elanco’s new global headquarters on the White River and Purdue’s vast presence in the state’s capital. The One Health Innovation District is designed to be a unique ecosystem of support for innovators to catalyze and speed new ideas through development. It’s built on 4-pillars:

- Research Institute: A shared-use facility will provide offices, wet labs and incubators that support collaborative research and rapid scientific translation across microbiome science, computational biology, comparative genomics and livestock sustainability, as examples.

- Scale-Up Manufacturing: A dedicated scale-up studio will bridge research and commercial production, helping innovators overcome manufacturing barriers and bring new ideas to market.

- OneHealth Venture Studio: The OneHealth Studio — launched by Alloy Partners and Elanco — will unite researchers, investors, corporate partners and entrepreneurs to create and scale new One Health startups in Indiana.

- On-site Veterinary Clinic: An on-site veterinary clinic will offer real-world validation and application, serving as a flagship destination for One Health innovation.

With leading biotech companies in animal, human and plant health already clustered downtown, Indianapolis offers a rare environment where public, private, government and academic partners can work in sync.

“Indiana has a rich history in life sciences, manufacturing and innovation,” says Jeff Simmons, president and CEO of Elanco. “As home to life science leaders like Elanco, Eli Lilly and Company, Corteva Agriscience and Purdue to name a few, Indianapolis is ripe with talent and industry leaders, which is paving the way for the future economy of Indiana.”

Simmons envisions a “One Health economy” taking shape downtown — a model where universities, industry and the state move together to accelerate discovery and opportunity.

“Purdue has always been proud to partner with Elanco to advance our shared goals in health and innovation for our state,” says Purdue President Mung Chiang. “Working alongside companies such as Eli Lilly and Corteva Agriscience, our outstanding faculty and students advance One Health — the intersection of human, animal and plant health, especially in the One Health Innovation District in Indianapolis.”

“What we’re creating sets Indiana apart: a global node for One Health convergence and collaborative research that has never been explored at this scale — until now,” Simmons says.

Curiosity can’t drive every single innovation. Industry could not have done what they did without the knowledge we generated. Our knowledge could not have had an impact without industry.

Ramaswamy Subramanian

Professor of biological sciences and biomedical engineering, director of the Bindley Bioscience Center

Translating ideas into impact

Breakthroughs in animal, plant and human health usually begin in the lab, but turning those breakthroughs into solutions requires a different brand of expertise.

Pairing Purdue’s research excellence with Elanco’s real-world development expertise initiates innovation at a pace neither could muster on their own. Each partner strengthens the other — and breakthroughs reach the world faster because of it.

“By combining Elanco’s market insight, commercialization expertise and infrastructure with Purdue’s cutting-edge research and talent pipeline, we create a partnership that accelerates innovation from concept to impact,” says Tim Bettington, Elanco’s executive vice president of corporate strategy and market development.

Ramaswamy Subramanian, professor of biological sciences and biomedical engineering and director of the Bindley Bioscience Center, explains that innovation usually occurs through one of two distinct approaches.

First is the traditional academic approach, focused primarily on the generation of knowledge, followed by attempts to apply that knowledge with real-world solutions.

However, the second approach identifies a real-world problem, then works to develop innovations to solve it. This approach is what makes the Purdue-Elanco partnership so effective.

“Curiosity can’t drive every single innovation,” Subramanian says. “Industry could not have done what they did without the knowledge we generated. Our knowledge could not have had an impact without industry.”

The shared space in Indianapolis strengthens this feedback loop, helping ideas move from concept to clinical trials far more quickly. “Because of this, I would see the impact of my science in my lifetime,” Subramanian says.

“Academic researchers often make fundamental discoveries whether about molecules, disease, etc.,” says Daniel Golden, Elanco’s vice president and global head of research, discovery and breakthrough innovation. “Corporate scientists, with their focus on application and commercialization, are adept at taking these basic discoveries and translating them into practical solutions, products or therapies.”

Preparing tomorrow’s One Health leaders

Purdue is already a leading source of One Health talent, and new degree programs are expanding that pipeline even further. The new biomolecular design and radiopharmaceutical manufacturing programs align with emerging workforce needs in Indianapolis and across the country.

To continue pushing the field forward, Purdue is hiring a dozen new faculty in One Health clusters, with strengths spanning integrated health, pharmaceutical manufacturing, advanced chemistry, drug discovery, radiopharmaceuticals and AI-driven biomolecular design.

Purdue has also launched GEM-AI, a new research area in genomics, multiomics and AI that unites researchers exploring how genes, molecules and systems interact to shape health and disease. The new research area analyzes massive biological datasets using AI to detect patterns and relationships that humans might otherwise miss.

Why One Health matters to you and me

One Health reveals deep health-related connections across our families, our pets, the food we eat, the air we breathe and the environments we encounter every day.

“We did not evolve independent of each other,” Subramanian says. “To assume that changes in plants or the agricultural ecosystem doesn’t affect us or vice versa is untrue.”

Studying diseases across different species can reveal clues we’d never find by looking at humans alone. For example, many animals develop the same diseases humans do, but their genetic diversity compared to humans makes it easier to pinpoint the genes that make someone more likely to be diagnosed with a condition like breast cancer. These findings can lead to better treatments for both humans and animals.

Our microbiome also links us to the world in which we live. Trillions of microorganisms live on and inside us, and our environments — from the region where we live to the people and pets surrounding us — shape the microbial communities that influence how we think, feel and behave.

“This means human health can’t be studied in isolation,” Subramanian says. “It’s deeply tied to the animals, plants and environments around us. That’s the essence of the One Health approach Purdue and Elanco are advancing together.”

What we’re creating sets Indiana apart: a global node for One Health convergence and collaborative research that has never been explored at this scale — until now.”

Jeff Simmons

President and CEO of Elanco

Keeping Purdue’s ‘pink mitten’ holiday tradition alive

The PMU pink mitten is more than a Christmas tree ornament for Susan Hayhurst. It’s a treasured memory of her mom, Ruth Krauch.

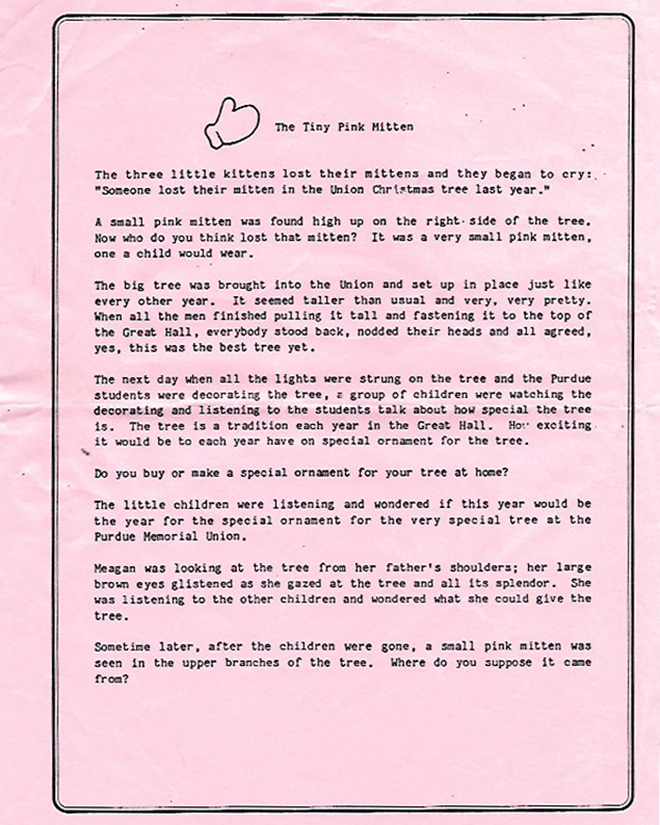

As legend has it, a celebrated Purdue holiday tradition — the fable of the pink mitten — originated in the most innocent of ways.

As she had done so many times before, Ruth Krauch was showing the Purdue Memorial Union Christmas tree to a group of schoolchildren, a favorite assignment in her role as the Union’s chief hostess. But during this particular visit sometime in the early 1980s, a young girl discovered a decoration that Krauch had never noticed on any previous tour.

A small pink mitten was hanging from the branches of the enormous tree.

“Why is that mitten on the tree?” the girl inquired. “Where did it come from?”

Krauch didn’t know, but she felt an immediate spark of inspiration to create her own origin story for the tiny ornament. The CliffsNotes version: A little girl visiting the Union’s Christmas tree with her father decided to contribute a special decoration for the tree by leaving her pink mitten hanging from its branches.

For years to come, Krauch would enthusiastically share the story of the pink mitten to every day care group, class of grade schoolers, church youth group and Scout troop who joined her on a holiday tour at the Union.

“Thousands of local children and families who came to see the tree at the Union would have heard that,” says Krauch’s daughter, Susan Hayhurst, a 1982 Purdue graduate. “In any given Christmas season, it would have been hundreds of children.”

More than 40 years later, Krauch’s story remains a treasured part of Purdue’s Holidays at PMU tradition. Each year when the Purdue Student Union Board’s members decorate the tree, they hang a pink mitten decoration (insider secret: they actually have two in case one goes missing) about two-thirds of the way up the tree — visible, but high enough to remain out of reach for any mitten enthusiast who might be tempted to take it home.

Those in the know make it their mission to locate the mitten each year when they visit the Union to see the tree. It’s an annual part of many families’ holiday festivities — and that’s what makes it especially meaningful for Hayhurst.

The story will always provide a treasured memory of her mother, who passed away in 2020 at age 94. But it’s also a special piece of the holiday season that she shares with the community where she grew up and with all of her fellow Boilermakers.

“This story means a lot to our family,” she says. “But as alumni, it means the world, too.”

Boilermaker roots

To put it mildly, Purdue and the Greater Lafayette area are a big part of Hayhurst’s identity.

The West Lafayette native attended Klondike Middle School and Harrison High School while both of her parents worked at the university.

Her dad, Herbert, was the Extension wildlife specialist for the state of Indiana and an assistant professor at Purdue. And her mom worked at the front desk for the Union Club Hotel and as chief hostess for Purdue Memorial Union and Stewart Center.

“After she died, I was incredibly touched at the cards I got from West Lafayette, and they said Ruth was hospitality personified at Purdue,” Hayhurst says. “She was just a hostess with the mostest.”

Hayhurst recalls her mother being specifically requested by university leaders like Arthur Hansen and Steven Beering to hostess Purdue President’s Council events.

“Dad and I got to know quite a few of them, and we were invited to different things because they wanted Ruth’s family there,” Hayhurst says. “It was because of Mom. She would make sure that their event at the Union went on as scheduled. That was commonplace for her.”

Hayhurst also worked at Purdue, both as a student and in the years after graduation. As a Boilermaker undergrad, she wrote for the Exponent student newspaper and Purdue Alumnus magazine. She later returned to the Alumnus to serve as assistant editor under her mentor, Gay Totten, before fate intervened.

She was training to succeed Totten as the magazine’s editor when she met her future husband, Terry, on a blind date. Four months later, they were engaged. They’ve been operating a family farm 10 miles south of Terre Haute ever since, producing corn, soybeans, wheat, hay and raising beef cattle.

“As Gay used to say, he swept me away to the farm,” Hayhurst jokes. “The city girl who married the farm boy knew nothing about farm life.”

But trips back to her hometown are still a regular thing for Hayhurst — she calls them “Purdue mental health days” — especially during the Christmas holiday season that is so important to her family.

“It’s a recharge for me when I go up there,” she says. “It’s my old haunts, and I can walk through campus, and I smile the entire day.”

Sharing with a new generation

A couple years ago, after her mother had passed, Hayhurst was walking through a grocery store parking lot in Terre Haute when she noticed an unusual object lying on the ground. She interpreted it as a sign from above.

“I looked down at the ground and there was this little pink mitten,” she recalls. “And I just immediately started crying and thought, ‘Gosh, that was dropped by a child for me.’ So I picked it up and brought it home. It’s hanging over a picture of my mom on my desk. This is all really near and dear to me.”

It also motivated her to share the pink mitten story with an even wider audience of Boilermakers, more than four decades after her mother created it for the local schoolchildren she hosted at the Union. With encouragement from friends and family, she plans to turn the story into a children’s book that Purdue families can share for many years to come.

The tradition of Purdue is in the hearts of hundreds of thousands of people. And I love that Mom’s story of the pink mitten is part of that tradition for so many people. For me, it’s almost like a living, breathing gift that Mom gave.

Susan Hayhurst

BS interdisciplinary consumer and family science ’82

She knows it’s an idea her mom would love, not only because new generations of children would be exposed to its message about the importance of giving, but also because it would help the story remain part of the Purdue holiday tradition that Krauch loved so dearly.

“It means the world to me that Mom developed this story as the result of a young child calling her attention to this pink mitten in the Great Hall Christmas tree. Mom always had an eye and heart for young children — in our neighborhood, with friends, everywhere. To me that really personifies how much she enjoyed children and she felt led to make a story like this,” Hayhurst says.

“The tradition of Purdue is in the hearts of hundreds of thousands of people. And I love that Mom’s story of the pink mitten is part of that tradition for so many people. For me, it’s almost like a living, breathing gift that Mom gave,” she adds. “When the little girl pointed out the mitten and then Mom wanted to make it into a tour story and share it, that’s what Mom was all about. She loved to share and show affection and love.”

Purdue’s 2 locations create unmatched opportunities for materials engineering student

Janvi Prasad discovers academic growth, success and inspiration commuting between West Lafayette and Indianapolis

Motivation and consistency are key to achieving your career goals. That’s a truth Janvi Prasad knows by heart.

The Purdue junior dreams of working in the semiconductor industry and using her STEM skills to make a meaningful impact on the world.

One of her crucial small steps to reach this goal came last year when she regularly commuted from West Lafayette to Indianapolis to work in mechanical and materials engineering professor Babak Anasori’s lab — a trip made easy with the Campus Connect shuttle.

“Working in Indianapolis was a refreshing change — the environment was beautiful, and everyone in the lab was welcoming and kind,” Prasad says. “That experience helped me grow both academically and professionally.”

Taking small steps in Indy

Prasad, a native of the San Francisco Bay area, chose to attend Purdue for its strong engineering reputation and plethora of research and industry opportunities.

Interested in challenging herself and making connections in her field of interest, working in Anasori’s lab stood out as an opportunity she did not want to miss.

Among the most appealing aspects of the position was the opportunity to work with Anupma Thakur — a postdoctoral research associate in the College of Engineering and Prasad’s eventual mentor — who clearly communicated the research’s potential.

“As an undergraduate new to research, that level of clarity and support was extremely appealing. It made me feel welcomed and confident in stepping into a research environment for the first time,” she says.

Balancing work and life

In the lab, Prasad helps analyze titanium carbide MXenes, a class of 2D materials.

She’s excited to support more environmentally sustainable ways of processing these materials and expand their applications across fields, including in the semiconductor industry and in image sensors. These sensors can be found in commercial products, like digital cameras.

“Being involved at the Indy location gave me a valuable understanding of how my individual contributions fit into a much larger research effort. Learning how a bigger lab operates helped me develop a systems-level view of research, like how data collection, analysis and collaboration come together across different roles,” Prasad says. “That perspective has helped me work more efficiently and confidently in my academic and research projects at Purdue.”

She also feels grateful for the unique experience of learning in Indianapolis, balancing studies and life. “The friendly atmosphere and opportunities to connect with others made a big difference in feeling like part of the campus community,” Prasad says.

Looking back, her lab position — including the commute, new skills and mentorship — was invaluable in expanding her future opportunities.

Applying her skills in the real world

This summer, Prasad’s professional experience enhanced her summer internship at onsemi, a leading semiconductor manufacturer and sensor technology supplier based in Scottsdale, Arizona.

There, she modeled and ran mechanical and thermal simulations for semiconductor products in development, especially those for automotive applications.

“I’ve learned a lot about working in a professional environment and how to apply engineering principles to real-world problems,” Prasad says. “Being comfortable with technical discussions and documentation gave me a strong foundation going into this role.”

I’ve learned a lot about working in a professional environment and how to apply engineering principles to real-world problems.

Janvi Prasad

Purdue junior in materials engineering

Motivation for the future

Prasad says that her journey all started with stepping out of her comfort zone, staying curious, reaching out to mentors and professors, and being open to opportunities no matter where she found them.

“Seeing how the things I learn in class translate to innovation in industry is incredibly motivating,” Prasad says.

After graduating, she hopes to stay in the Midwest and continue building a career where she can apply her materials science skills for real-world impact.

“I’m especially interested in exploring and developing new materials in the semiconductor field,” Prasad says. “I hope to contribute to designing more efficient chip models and pushing the boundaries of what current technologies can do.”

Purdue and Kiewit are building the future of construction engineering and management

How do you keep an entire industry innovating? By educating the next generation of leaders

This story highlights one of the many ways Purdue teams up with corporate partners to create solutions for complex global challenges. Learn how your organization can collaborate with us.

Shared knowledge is the foundation on which the Purdue and Kiewit partnership is built.

The university and company have a deep history of joining forces on everything from coursework to advisory councils to conferences. A recent component of the collaboration, which has rapidly grown to become its centerpiece, is the Kiewit Scholars program.

Kiewit, one of North America’s largest construction and engineering companies, has a longstanding tradition of prioritizing workforce development. “Part of our culture, which started all the way back when Peter Kiewit founded the company, is that we grow our people,” says Jim Rowings (BSCE ’75, MSCE ’79, PhD ’82).

As chief learning officer and vice president of Kiewit University, Rowings oversaw the education, training and development programs of Kiewit’s 31,000-plus employees. In that role, he also worked with now-President Mung Chiang and others at Purdue to translate the ethos of Kiewit University into the Kiewit Scholars program — with an eye toward preparing a new generation to lead in a rapidly changing world. “To always be training and teaching is who we are,” he says.

Kiewit Scholars

Purdue is one of just five universities that Kiewit tapped to prepare the workforce talent that the entire construction trade will need.

Tyson McFall-Wankat (BS agricultural economics ’09) serves as project manager for undergraduate initiatives in the College of Engineering. She says, “Kiewit recognized that the industry, as a whole, is aging. They anticipated that there was going to be a time of large-scale retirement, and that they would need a younger generation prepared to jump into leadership positions without as many years under their belts as their predecessors had when they took on those senior roles.”

Kiewit Scholars, which is open to select majors in the Purdue Polytechnic Institute and the College of Engineering, is preparing students to fill those roles. Purdue’s first Kiewit Scholars cohort started in fall 2022. Students are eligible to participate in the program starting their sophomore year, and it provides generous scholarships that are renewable for up to six semesters.

“We intentionally cap the program at 21 students, seven per cohort year,” McFall-Wankat says. “The smaller size allows our students to get to know each other and to become comfortable working together.”

Special classes, internships, field trips and networking events are all part of the program, but its hallmark is the rare opportunity for Purdue students to be mentored by high-level Kiewit executives, such as Tom Shelby (BS building construction management ’81), an executive vice president at Kiewit and president of the Kiewit Energy Group.

“Leadership and the ability to communicate is so critical to our business,” Shelby says. “And I enjoy talking with the students. Sometimes we’re in an informal setting, sharing a meal, and sometimes we’re in the classroom talking about real-world, on-the-job scenarios.”

When you’re working with a place like Purdue, you’re going to get access to a lot of really smart people, and you’re going to see cutting-edge things that you can take back to your company.

Tom Shelby (BS building construction management ’81)

Executive vice president, Kiewit

President, Kiewit Energy Group

“It’s amazing for students to have the opportunity to get to know Tom,” McFall-Wankat says.

Alana DeVilbiss (BSCE ’25), a Purdue civil engineering graduate student, agrees: “Kiewit has helped me strengthen my technical, leadership and professional skills early in my career,” she says. “Working with a company like Kiewit as a student provides hands-on experience across multiple sectors of construction that develop my skills as a young professional.”

In addition to ongoing mentorship, students benefit from workshops on professional development, teamwork, conflict resolution and negotiations. These interactive workshops focus on helping students improve their confidence and strengthen their leadership skills.

“We bring in improv actors to work with students on training their brains to think quickly. It’s a skill that helps them remain calm so they can navigate challenging situations better,” McFall-Wankat says. “Something that’s been mentioned to me quite a bit is how much the workshops have helped our graduates on the job.”

Day in the life presentations are another key component of the program. “Purdue alumni, Kiewit employees and others discuss their career paths: what they’ve learned and advice that they have,” McFall-Wankat says. “We also do a field trip to a Kiewit job site to just get our feet on the ground and really see what it’s like to work in this industry.”

Connecting classroom and construction site

Bryan Hubbard (BSME ’88, MSE ’90), a Purdue professor in the School of Construction Management Technology, plays an important role in uniting classroom knowledge with hands-on learning. Hubbard has taught roughly 20 different courses since coming to Purdue in 2007. A current area of focus for him, and for Kiewit, is industrial construction.

“Industrial construction is unique to our program at Purdue, and it’s also a strong focus area for Kiewit,” he says. “It’s part of a concentration called infrastructure construction. So it combines both industrial construction — such as wind and solar energy, power plants, chemical plants, chip and fab manufacturing plants — with the other side of that concentration, which is what we call the heavy civil: bridge and road construction. When you combine bridge and road and industrial, that’s a big portion of Kiewit’s work.”

Hubbard adds that Purdue students love learning from industry people and benefit from having materials in the classroom that are from an actual project.

Louis Mariacher, a senior in the Purdue Polytechnic construction management program, says, “Working with an industry leader like Kiewit has been incredibly valuable, especially so early in my career. It gives me the chance to experience complex projects and learn the strategies and tools that make them successful.”

“It’s great to have real-world materials: plans, specs, quality control information,” Hubbard says. “We have someone from Kiewit who works in their solar fields walk our students through the process of setting up a construction site — the productivity issues, the cost issues, the quality control issues. We’re preparing them for all that happens on a job site while they’re still here in school.”

Benefiting an entire industry

Kiewit’s commitment to training future leaders for the construction industry isn’t simply a matter of preparing good workers for careers at Kiewit. It supports the larger goal of developing a quality workforce for the construction industry as a whole.

“If we train a lot of people and they go out and follow the way we like business to be done, it’s going to be good for us,” Shelby says, “and it’s going to be great for the industry.”

Rowings agrees. “The culture of Kiewit is to train and develop our people,” he says. “In a sense we are teaching them how to be professors in their own areas of expertise. But we want them to grow those skills of developing young people and staying engaged because as they advance in their careers, these are the people who will be coming behind them and moving up with them.”

Staying connected to innovation, particularly in areas such as AI and workplace safety, is another benefit to Kiewit in its partnership with Purdue.

“We need to keep our workers safe,” Shelby says. “So, we put a lot of effort into understanding safety and how we can support the industry that way.”

AI is going to play a key role in the future of the construction industry. It’s an innovation that Kiewit anticipated years ago and that informs its partnership with Purdue.

“When you’re working with a place like Purdue,” Shelby says, “you’re going to get access to a lot of really smart people, and you’re going to see cutting-edge things that you can take back to your company.”

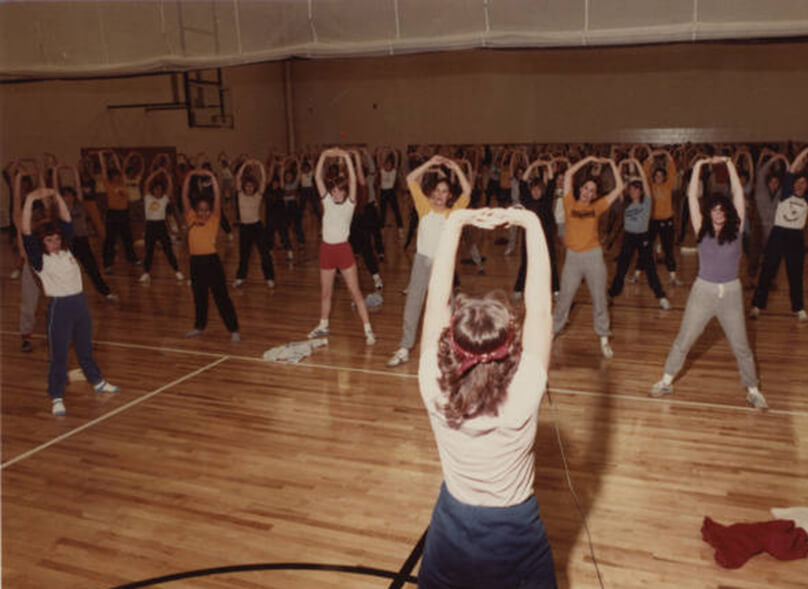

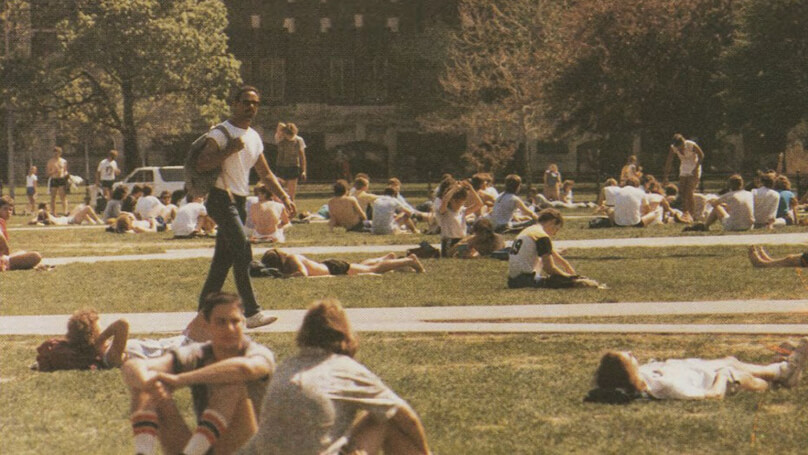

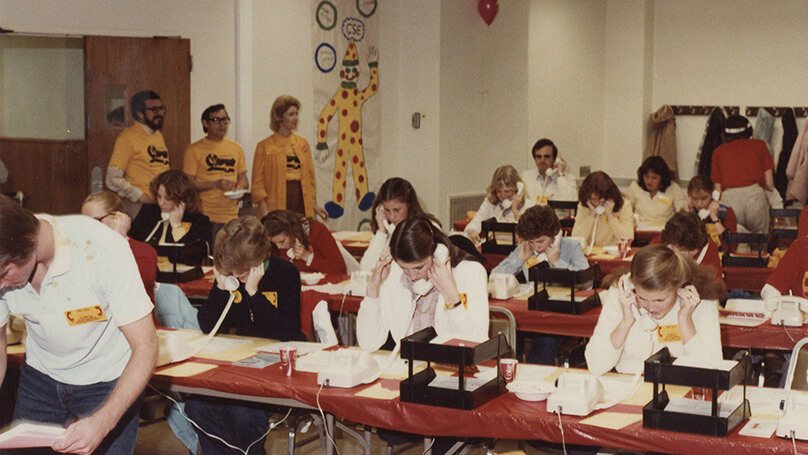

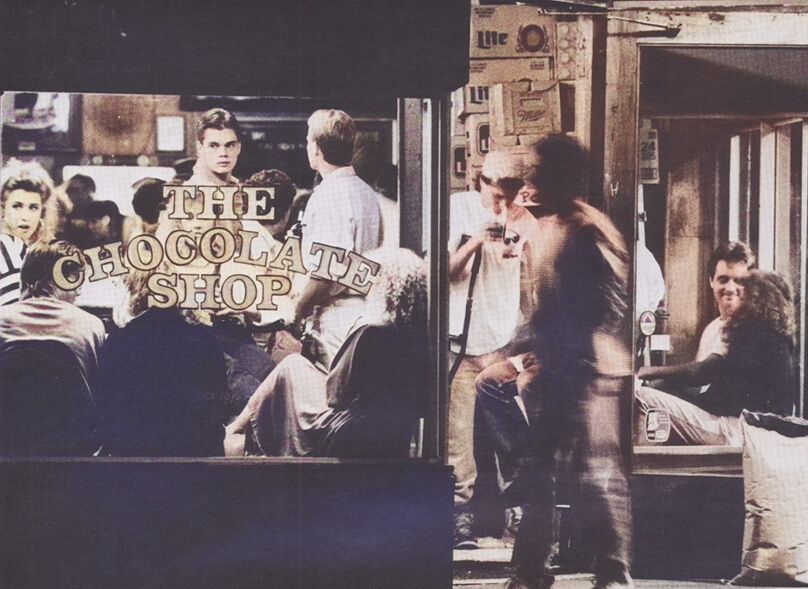

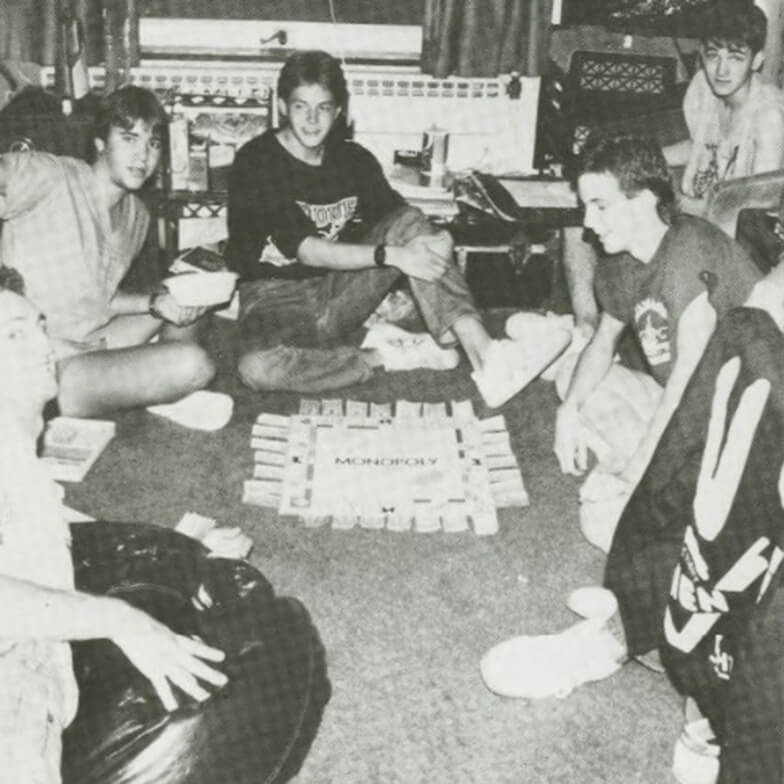

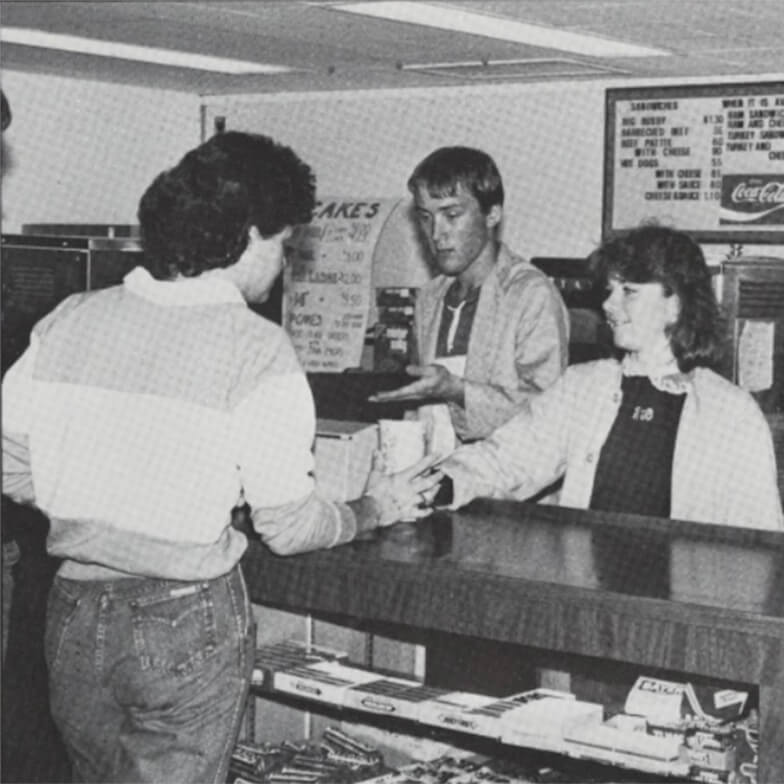

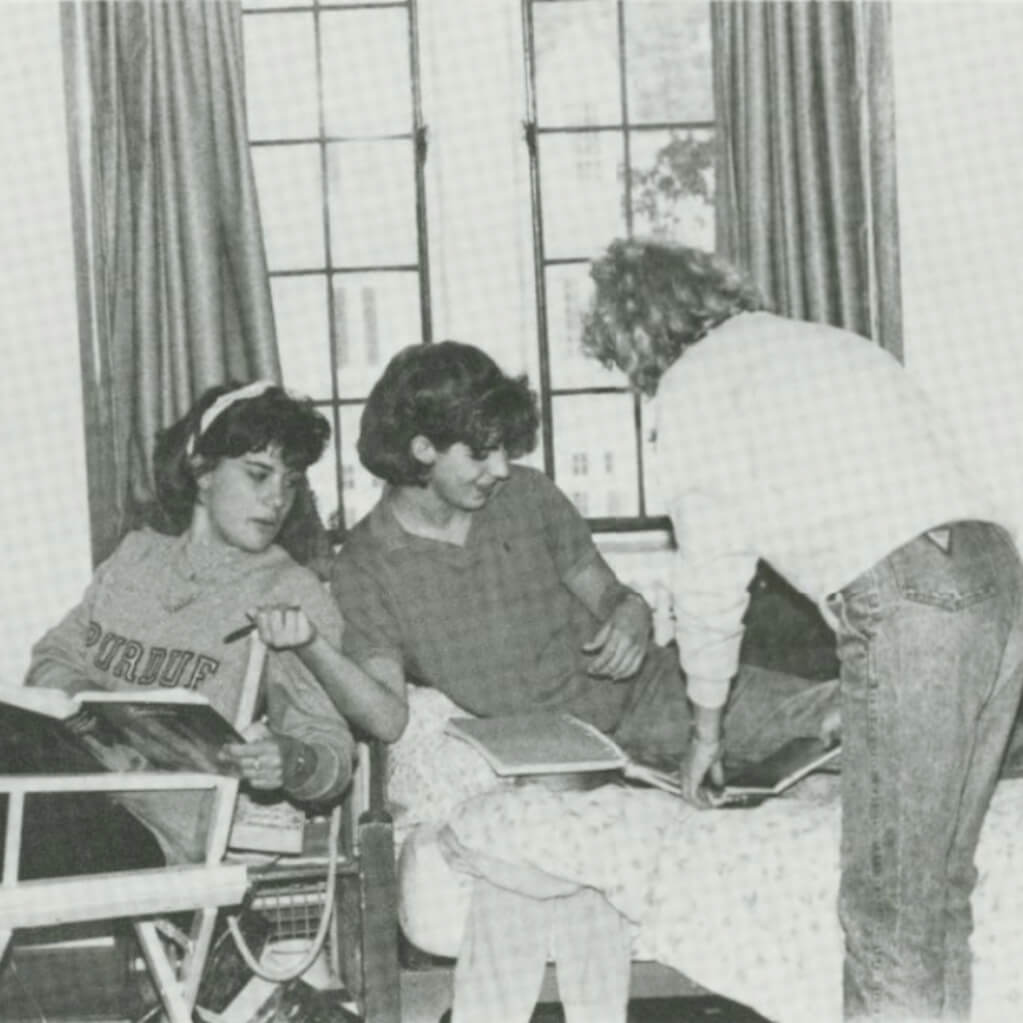

Boilers just wanted to have fun: Purdue student life in the ’80s

Visting the Sweet Shop between classes, or going to one of the many long-gone night spots afterward depending on which one had the best promotion that night. Sliding down snowy Slayter Hill on a borrowed lunch tray. Stopping during a walk through the mall to hear Brother Max preach and argue with students. Greek life. The birth of the Breakfast Club. Attending the Purdue Grand Prix and the many social events that took place the week of the race. And so much more. This was life at Purdue in the totally rad 1980s.