Purdue alumna is leading NASA to the moon, Mars and beyond

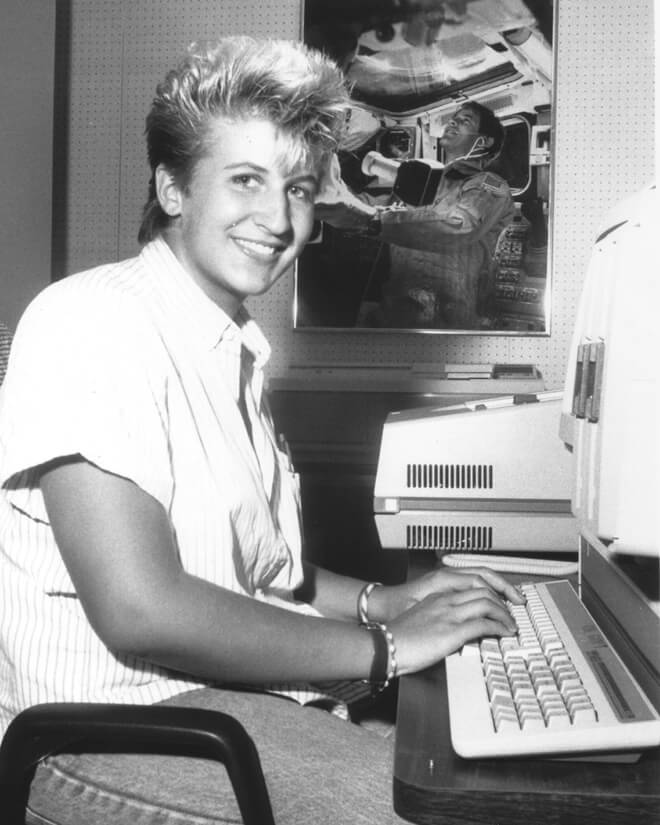

As the director of engineering for NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Julie Kramer White is helping the agency reach historic goals.

Julie Kramer White is an aerospace titan rooted in the Midwest

Texas sunlight, mercifully diffused by an overcast sky, fills Julie Kramer White’s corner office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC). It casts a glow on the moments and memories that cover the walls around her desk — symbols representing decades.

Family photos with her daughter and husband. A framed print honoring her Old Masters Program presentation at Purdue in 2015. The day she met then-President Barack Obama, who later mentioned her by name in a speech on the Orion capsule’s successful flight test: “When an American is the first human to set foot [on Mars], we’ll have Julie and her team to thank.”

Kramer White (BS aeronautical and astronautical engineering ’90), director of engineering for JSC, beams as proudly in person as she does in each photo. The view from her standing desk extends for miles across Houston, and out past the sailboats on Clear Lake. But in her head and her work, she remains firmly grounded.

The large “Keep Calm and Carry On” print on her wall is autobiographical. Having overseen structural design on space shuttle orbiter vehicles for a decade; having worked through both Challenger and Columbia accidents; having led design of Orion, NASA’s newest crew capsule — she is steadfast.

Towering, despite her average stature. Welcoming, despite her extraordinary status.

Hoosier State credentials

Kramer White didn’t want to be a doctor like her father. A broad public push in the ’70s encouraged her into STEM, and as a card-carrying member of the James Doohan International Fan Club — Scotty, from Star Trek — aerospace engineering was her field. But having grown up in the Indianapolis suburb of Zionsville, she was sometimes sheepish about being a Hoosier.

“I applied to a lot of different engineering schools around the United States, you know, MIT, Stanford. But honestly, what kept me in state was the great economic value. Plus, I could go home on the weekends and steal all the food out of my parents’ refrigerator,” she says smiling, now a knowing parent of her own college student.

But when she arrived at JSC for her co-op and explained to people that Purdue was in Indiana, she got an eye-opening surprise: “One of the senior engineers pulled me aside and said, ‘We know where Purdue is … In fact, I couldn’t get into Purdue … So stop saying that.’”

Launching a career at NASA

Kramer White has worked at JSC since the mid-’80s. She first stepped foot there as a co-op student conducting thermal analysis. She interviewed for that co-op in January 1986 in what would be a pivotal time for NASA. Shortly after, the Challenger shuttle launch shook the world.

“I remember being out in front of the co-rec, and on the big screen they were showing the launch. We saw the accident happen, and then a week later I got my job offer for my co-op position,” she says.

With Boilermaker grit, she knew not to shy away from failure. She didn’t hesitate to take the job. On that first co-op tour, Kramer White did thermal analysis of the solid rocket boosters and the failed O-ring joint at fault in Challenger. She was thrilled to be on co-op again when the Discovery launch marked a shuttle’s return to flight in September 1988.

She continued working at JSC after graduating from Purdue in 1990. Apollo-era veterans like Stan Weiss, who had worked on lunar landers, mentored her through those early years. They gave her good projects, let her make mistakes and watched her grow in her roles. She rose the ranks to working in the chief engineer’s office for the space shuttle program.

Kramer White is proud to have touched every single orbiter. She loved her trips to Palmdale, California, for their maintenance and modification periods, and the hands-on nature of that work. Her responsibilities spanned from maintenance to flight certification of the wings, tail, flight surfaces and other structures. A lot of the developments involved making components lighter, improving capabilities and allowing heavier payloads to support building the International Space Station (ISS).

“I became very attached to the orbiters. They’re a little bit like children, with their own unique attributes,” she says, pausing, stifling a sigh. “Columbia, being built very early in the program, had a lot of unique attributes.”

I became very attached to the orbiters. They’re a little bit like children, with their own unique attributes.

Julie Kramer White

Processing the loss of Columbia

In February 2003, Kramer White was in California for training when she got an early morning call from her husband, Robby. Columbia had broken apart on reentry. She had to get back to Houston.

She immediately called a travel service and negotiated a 9 a.m. flight out of San Jose.

When she arrived, it was already clear something had happened with the wings. Her job those first few weeks was to drive to various debris fields near Lufkin, Texas, and identify the pieces. She spent the following five months at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, as part of the failure analysis and materials teams. The workload was her way of dealing with the loss.

“For those of us who spent our careers working on this spacecraft, really your entire reason for being is to help prevent something like this from happening. So it was really hard for us, having lost the vehicle as well as the crew,” she says. “To be out in the field, working long days, long weeks, down in Florida, working towards understanding what happened and getting us back to flying, and dealing with the corrective actions that fell out of that — for me, that was the best place to process the accident.”

Building a family, and a spacecraft

In 2014, Kramer White cheered from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station as the Orion spacecraft successfully completed an uncrewed launch, orbit and splashdown. It was a proud moment for her as chief engineer for the spacecraft, which is designed to journey to the moon and Mars.

Kramer White took a leave of absence afterward, taking time to reset and focus on herself. She and Robby had a child, Cecelia.

Returning to work at NASA’s Engineering Safety Center, she soon saw an opening for chief engineer on the Artemis mission’s crew capsule. Having worked for more than a decade on a space shuttle vehicle design, she couldn’t miss the opportunity to make something completely new.

“Sustaining a vehicle is totally different than taking it from early concept development through requirements, bringing on a prime contractor, and then dealing with all the trials and tribulations it takes to get from paper to flight,” she says. “I pestered the engineering leadership to death, telling them why I would be great at this. They eventually acquiesced, and I stayed there for 11 years.”

Cecelia grew up alongside the Artemis crew capsule, which would later be named Orion. Cecelia went to every major flight test. She frequently heard Mom on the phone at the kitchen table, debating design decisions well into the evening.

Balancing the work, Kramer White also leaned into her crafting hobby, supporting Cecelia’s interest in musical theater by building sets and sewing costumes, and creating just about anything out of papier-mâché. Cecelia didn’t want to work at NASA — until she found out they had internships for graphic arts majors.

“Last summer she worked at JSC doing illustration for Artemis public outreach. She came home every night and peppered me with questions on programs, people, history, relationships, NASA vision and mission,” Kramer White says. “She loved the people and their passion for their work, and using her skills to represent the mission through her art. She could make the mission accessible to normal — non-engineering — people.”

Kramer White has been director of engineering at JSC since 2021, serving as deputy director for three years before that. With the space shuttle program retired and ISS having less than a decade remaining, NASA is letting commercial operators dominate low Earth orbit (LEO). Kramer White has eyes on the moon and beyond.

“We’re busier than ever. I’m looking at integration on the lunar surface, in-situ resource utilization, extending our human presence away from LEO,” she says.

It’s a big opportunity for anyone looking to NASA for a co-op or internship, like she did: “You’ll show up, they’ll give you a job and you’ll say, ‘I can’t believe they’re letting me work on this.’”

You’ll show up, they’ll give you a job and you’ll say, ‘I can’t believe they’re letting me work on this.’

Julie Kramer White

BSAAE ’90

A lifetime of service

A diverse employee base is important to NASA’s future success, Kramer White says. She makes regular visits to Purdue, inspiring students in the Women in Engineering Program and Minority Engineering Program with opportunities in aerospace.

Her lifelong dedication has earned Kramer White a long list of NASA medals and awards, plus the 2017 Outstanding Aerospace Engineer and 2023 Distinguished Engineering Alumni awards from Purdue. Like the Apollo-era veterans who ushered her entrance into public service, Kramer White’s contributions continue to form pillars underneath the next generation of leaders in aerospace.

But 30 years of Texas sun can’t bleach the Midwest modesty out of her. Even in her corner office, inches away from a picture with a United States president, she still can’t believe it. She’s astounded to see her name alongside others who have received those awards.

Like her NASA mentors, Kramer White would likely deny it — but she, too, is a titan of aerospace.

Written by: Alan Cesar, acesar@purdue.edu

This story originally appeared in the 2023-2024 issue of Aerogram Magazine.