Podcast Ep. 96: Sangtae Kim on Leading the Davidson School of Chemical Engineering and the Importance of Purdue’s ‘Excellence at Scale’

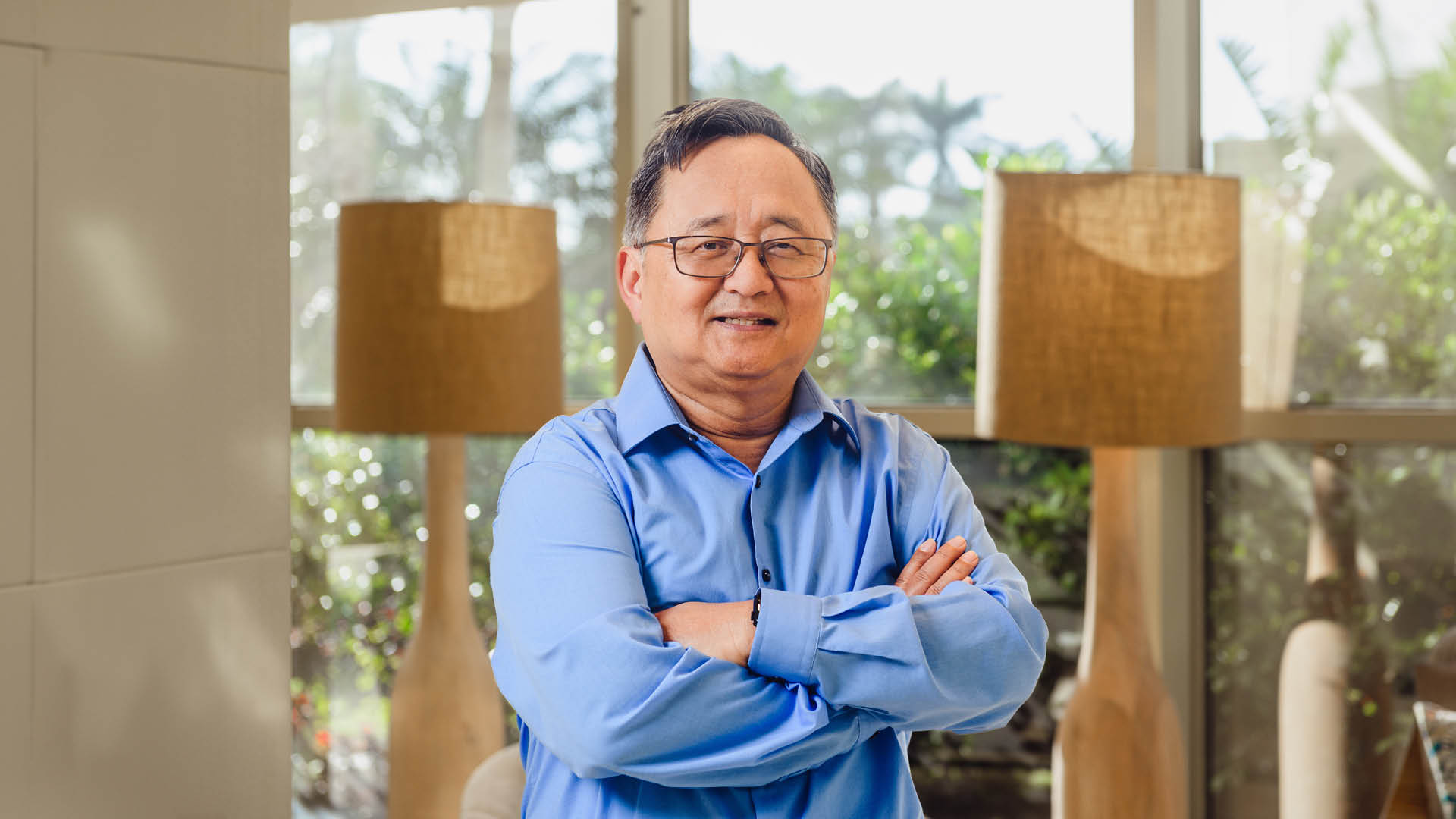

In this episode of “This Is Purdue,” we’re talking to Sangtae Kim, the Jay and Cynthia Ihlenfeld Head of Chemical Engineering and Distinguished Professor.

Sangtae dives into his family background — including what it was like growing up in a family of educators, his career at Eli Lilly and what brought him back to academia to lead Purdue University’s Davidson School of Chemical Engineering.

Listen as Sangtae discusses the significance of the growing number of women majoring in engineering and Purdue’s culture of solution-oriented students.

“Be part of the solution, not the problem, right?” Sangtae says. “It’s advice that I don’t have to give because that’s the nature of Purdue students and graduates.”

Plus, he shares what it means to him to be guiding and mentoring those walking in the same shoes he once did and his admiration for Purdue’s “excellence at scale.”

- Learn more about Sangtae Kim

- Learn more about the Davidson School of Chemical Engineering

- Learn more about Purdue’s College of Engineering

Full Podcast Episode Transcript

Kate Young:

Hi, I’m Kate Young and you’re listening to This Is Purdue, the official podcast for Purdue University. As a Purdue alum and Indiana native, I know firsthand about the family of students and professors who are in it together, persistently pursuing and relentlessly rethinking who are the next game changers, difference makers, ceiling breakers, innovators? Who are these boilermakers? Join me as we feature students, faculty and alumni, taking small steps toward their giant leaps and inspiring others to do the same.

Professor Kim:

I’ll always have this short phrase or expression, be part of the solution, not the problem. I almost don’t have to give that advice because that’s also the nature of the Purdue students and graduates. Company after companies say that they really like to recruit our students and hire them because that’s actually what happens. They inevitably are part of the solution rather than creating problems and headaches for their companies. They are doers, they get things done, they accomplish things and companies just love them.

Kate Young:

In this episode of This Is Purdue, we’re talking to Sangtae Kim, the Jay and Cynthia Ihlenfeld head of Chemical Engineering and distinguished professor. Professor Kim dives into his family background, including what it was like growing up in a family of educators, his career at Eli Lilly and what led him back to academia to take on the role of leading Purdue university’s Davidson School of Chemical Engineering. Professor Kim also discusses the significance of the growing number of women majoring in chemical engineering and Purdue students’ solutions-oriented mentality. Plus he shares what it means to him to be guiding and mentoring those walking the same shoes that he once did and his admiration for Purdue’s excellence at scale. Professor Kim kicks things off by sharing more about his childhood academic background and journey to Purdue University.

Professor Kim:

I was born in Korea, but at a young age, age seven, I immigrated to Montreal, Canada. My father was pursuing his PhD in mathematics at McGill University. Both my parents are mathematicians, so from a very early age I had an interest in mathematics as well as physics and chemistry and the various disciplines. Also, there are a number of people in my family who are professors. My father’s younger brother was also a professor. My mother used to teach high school mathematics in Korea, so we come from a family of educators. I knew I wanted to be a professor, but I didn’t know exactly which area. But then in high school, I really liked my chemistry course and my high school chemistry teacher introduced me to the field of chemical engineering and encouraged me to study that in college. That’s how I became a chemical engineer. I was also encouraged by my high school teacher to look at some of the top universities in the US.

So from grade 11, which is where high school ends in Montreal, I came to the California Institute of Technology, more commonly known as Caltech, and I did my undergraduate there in the mid-seventies, ’75 to ’79, and then I went on to do a PhD at Princeton University and finished there in early 1983. And then in the first part of my career I went to the University of Wisconsin Madison in the Department of Chemical Engineering and I was there for about 15 years. Then somewhat unexpectedly, I was recruited away to an executive position by the pharmaceutical industry, initially at Park Davis Pharmaceuticals in Ann Arbor, Michigan and then Eli Lilly in Indianapolis. And that’s what brought me closer to Purdue. And in 2003 I had the opportunity to come back to academia and with the opportunity at Purdue, both the mechanical engineering and chemical engineering, and I was the inaugural Fetterson distinguished professor of mechanical engineering and distinguished professor of chemical engineering in 2003.

Kate Young:

Professor Kim dives further into his career at Eli Lilly and why he decided to come back into the world of academia.

Professor Kim:

So in the six years I was in the pharmaceutical industry, I did not work as a chemical engineer. I was actually the executive in charge of research IT at a time when the pharmaceutical world was undergoing a very significant transformation because of the sequencing of the human genome. The so-called genomic revolution was happening at the same time as the IT revolution with the emergence of the internet and the whole idea of distributed computing and distributed information databases connected by the corporate intranet, which would be like the internet inside a company. And so I was in that world helping lead that transformation. After six years of that, the transition was pretty much complete. I looked back to having the exciting life of research in academia and also applying these ideas that I had seen in the pharmaceutical world. Upon my return to academia, Purdue had a very big initiative at the intersection of information technology and engineering, and that was the goal of the Fetterson professorship. And so I saw that as the great opportunity to take what I had learned in industry and apply them again in the academic world.

Kate Young:

Professor Kim highlights a few mentors who helped steer his education and career path.

Professor Kim:

Definitely Mr. Brown, my high school chemistry teacher, I would consider him my first mentor beyond my immediate family. He had an interesting history. He originally came from Jamaica and he always regretted not taking the opportunity to go to Caltech when he was a young man. And so I think when he saw students in his class who he thought would benefit from that opportunity, he would encourage us to look beyond our immediate neighborhood and the region near the school and look at great universities elsewhere. And so without Mr. Brown, I probably would not have gone on to Caltech and probably would not have been a chemical engineer. And then once in academia, as I mentioned, I chose Wisconsin because of its reputation. So there is a professor who just passed away in the year 2020, Professor Bob Bird. He goes by his nickname Bob, Robert was his actual name.

So Bob Bird was one of the legendary figures in the world of chemical engineering. Along with two co-authors, he created a landmark textbook known as Transport Phenomena, which brought that subject into the field of chemical engineering in the early 1960s. And I was recruited to Wisconsin to inherit that legacy as the original trio of Bird, Stewart, and Lightfoot were approaching retirement age. And then as I mentioned, the unexpected transition into the pharmaceutical world because of the IT and genomic revolution. I had an amazing three years at Park Davis Pharmaceuticals. It was one of the most successful periods in the history of that company, but in the year 2000, the company was acquired by Pfizer and I thought, well, that was an exciting three years and now I’ll just go back to the university world. But Dr. August Watanabe, usually goes by the name of Gus Watanabe, who was president of Lilly Research, convinced me to come to Eli Lilly after my three years at Park Davis, the actual challenge of joining Lilly at the time, in the year 2000, Lilly had unexpectedly lost a patent protection on Prozac.

And so I saw Lilly as an opportunity to see a different set of challenges. At Park Davis, the company was doing so well because of the launch of one of the greatest products in the history of the pharmaceutical world, namely Atorvastatin, also known as Lipitor. I think that eventually reached peak sales of about 14 billion a year. So the company was obviously going to do very, very well and was using that money to build up a world-class research organization. Lilly was in some sense the opposite challenge. Lilly already had a world-class research organization, largely built on the success of Prozac. Unexpectedly, the patent was lost three years before the expected expiration, and I think at that time Prozac was making about four billion dollars a year, almost all of that toward the end of the product life falls into the bottom line. Basically, the company was going to lose about 12 billion of expected revenues, much of which would be of course funding the research operations and research programs.

And so the challenge at Lilly was how do you keep a great organization through a very lean time, almost like a winter of hibernation until spring comes back. It took about three years to navigate that, and by the end of that three years, it was clear that we had done that successfully. And to this day, of course, Lilly is a very successful and independent company. When I was recruited, that was presented as a challenge. Dr. Watanabe said, “This company wants to stay independent, it’s important to Indiana, and of course all the people there.” The company really felt the answer was innovation, not cost savings through mergers and so on. And so really wanted to execute on that vision, and that’s the reason why I stayed on in the pharmaceutical industry and came to Lilly because that was something I could align with.

Kate Young:

As we heard earlier in this episode, professor Kim completed his undergrad at Caltech and went on to get his PhD from Princeton. I asked him what makes Purdue unique in his eyes after having experiences at these prestigious top tier universities?

Professor Kim:

Well, interesting thing about my career is that all of my education, both at undergraduate and graduate level, was in the small private universities. The undergraduate class at Caltech, every year there’s about 200 students, so the total undergraduate population is only 800. Purdue of course is a land grant university and both the University of Wisconsin and Purdue are land grant universities. And I think I was initially attracted to Wisconsin because of the reputation of the chemical engineering department there. But after I arrived and got infused with the culture and goals and aspirations of a land grant university, I think that was really my calling. So my entire academic career has been at the land grant universities, and of course Purdue right now, I believe we are the best and really the model of the original vision of the Morale Act.

Kate Young:

The Morale Act, also known as the Land-Grant Act Professor Kim just mentioned offered states an opportunity to sell plots of federal land in order to increase US agricultural and engineering expertise. Proceeds from these land sales would help fund the creation of universities that emphasized these subjects, as well as military tactics and classical studies. And Purdue University is Indiana’s sole land grant institution. Land grant universities are problem solvers and they were designed to give working class Americans their first chance at a college education. And you’ll hear more from Professor Kim on the boilermaker problem solving mentality and why companies recruit Purdue students for this very reason later on in the episode. Professor Kim shares one of his earliest memories from Purdue, which involved then Purdue President Martin Jischke.

Professor Kim:

One of my earliest memories of Purdue is one of my favorite memories because it really aligns with my thoughts about creating a world-class organization for education and research and so on. And it’s the president of Purdue who was here when I was recruited, and that’s Martin Jischke. Martin Jischke was also an engineer. I think his original field was aerospace engineering. I remember one of the faculty members asking him in one of the Q and A sessions, what are the metrics that you use to evaluate faculty and to create incentives for people to do better and become better and so on. He had a surprising answer. He told us that he doesn’t like to use metrics, and specifically he does not like to tell people what the metrics are, because his experience with engineers is once you tell them what the metrics are, they will game the system to get those metrics up.

And so you have to be very careful and strategic in setting a course for excellence. I think this is a very common theme nowadays, but he was way ahead of his time in his wisdom and understanding this. Today, the world of higher education is replete with stories of less than optimal behavior on the part of faculty and students or dysfunctional behavior because it’s all about number of papers and citations and this, but the thing you really want is impact. And so usually these numbers do align, which is why they became the metrics. But if you use them without thinking through the actual end game or the actual impact that you want to have, then you can end up in a situation with great metrics but not the impact.

Kate Young:

I asked Professor Kim how he thinks the Davidson School of Chemical Engineering has changed throughout the years.

Professor Kim:

One of the things that’s definitely changed, and I can’t take the full credit for it, was actually started by my predecessors two heads before myself. The idea that the main challenges and opportunities in chemical engineering are now really societal transformation. For example, the transformation of our energy infrastructure from fossil fuels to renewable energies. This is a very difficult technological transition. I predict it’ll take about 50 to 100 years to execute on that transformation and doing it in a way that leaves our civilization intact and without a lot of suffering. It’s not something that a single professor can do on their own. It takes teams of many different specialties, and beyond chemical engineering, collaboration with other disciplines in other fields.

And so I think the biggest change that I’ve seen in the past decade is our ability of our faculty to form these winning teams. Because typically the federal government programs to support such research are on the order of 40 to 100 million dollars type awards as opposed to, say, hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars for a single faculty member. So there’s a specific set of strategies that work very well to make sure that our proposals from our teams at Purdue have better than equal chance of winning. We want to be competitive and win more than our share of those awards. And I think the past decade in our field, in our department, in our school, the record shows that we’ve been very successful and certainly much higher than simple statistics of the number of entries and proposals.

Kate Young:

Are you a fan of Purdue basketball? Need something to help you get your Boiler fix before the next big game? Check out the Boiler Ball podcast to stay in the know and get inside stories all about the Purdue basketball program and beyond. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. Professor Kim says his favorite course to teach is the Junior Fluid Mechanics course, which is actually his original research area. He expands on why it’s rewarding to be a professor surrounded by eager young students, and how the Davidson School of Chemical Engineering has grown throughout the years.

Professor Kim:

It was the same area that I was recruited to teach at Wisconsin back in the early 1980s. At Purdue, I teach this chemical engineering course, the Fluids course. It’s the fall semester of the junior year, and we offer this course both semesters, but it’s the fall semester that is the larger class, typically over 100 students. The spring class are the co-op students and other students are off cycle, and that class might be less than a third in number. And so by teaching the course in the fall, I get to meet 75% of our undergraduates in person through the course, and I encourage them to come and see me, not just for help with the class, but to just talk about their career and what they want to do beyond Purdue and so on. And so both in terms of the topic and the way I teach it, but also the opportunities to interact with the students.

So we have almost 600 undergraduates in our program and the fact that three quarters of them have had a course with me. I have an email from a student who took the course three years ago asking for a letter of reference. He’s actually working in industry, but thinking of going on to grad school. And since I know who he is and I have my notes of my interactions with him, I’m more than happy to provide a reference. And so that’s why I like to teach this class because it gives me the day-to-Day contact with the students.

Kate Young:

What’s it like seeing them learn this chemical engineering and these courses? Through their eyes, you’re kind of seeing that?

Professor Kim:

Well, the immediate economic impact, because I like to remind our younger faculty that if you step back and look at the big picture, when they come into our program as sophomores, the value of their time, so for example, if they have a part-time job in the local stores or restaurants and so on, it’s basically around minimum wage or a bit better than that. So we’re talking about someone whose time is valued at 10 to $15 an hour. The range of starting salaries for chemical engineering graduates only three years later is somewhere in the 80 to 100,000 dollars per year. That’s their starting salary. And so if you change that to an hourly basis and roughly that’s about $50 an hour, so the value of their time has gone up by a factor of four or five in just three years. That is the value just in simple economic terms.

Now, of course, there are other factors that are beyond that, but just that alone, and then you multiply that by the 150 to 200 students that we graduate every year, and this is just the start for these young people, they’re going to do even much better than that in a few years. And so the economic impact, and the other curious thing right now is that starting about four or five years ago, the number of chemical engineering students actually declined significantly around the nation, somewhere around 30 to 50% decline at many universities. So Purdue, with our significant increasing engineering numbers, even though the percentage that go on to chemical engineering has shrunk, the total number of engineers has grown so much that the two factors compensate for each other, and so the number of students actually has increased slightly.

And so we’re now one of the biggest, if not the biggest chemical engineering programs in the nation at a time when industry has a lot of need, and there are a lot of positions and openings for chemical engineering graduates. We have large companies coming and telling us that chemical engineering is the only discipline in which they’re not able to meet their recruiting targets. And so we are in a really enviable position having one of the largest, if not the largest program. And so all these companies are now coming to Purdue if they’re looking for chemical engineers.

Kate Young:

Another significant growth metric that Professor Kim has seen throughout his more than two decades at Purdue, the increase in the number of women majoring in chemical engineering.

Professor Kim:

Well, I think first of all, and especially for people listening, I want them to know some amazing numbers and statistics. Because we say something so often that we start believing it must be true, but every year time marches on and things change. So it may surprise you to hear that the percentage of women in chemical engineering in our undergraduate students is 40%. So we’re not talking about 5% or 10%. It’s almost half. 40%. Now, it’s been like that for quite a number of years actually. And so women came into chemical engineering in significant numbers starting in the 1970s. And by the 1980s, certainly by the early 1990s, we were around one third or higher, and some programs even obtained 50/50.

Now, after having large numbers of women in our program, you might think, okay, in many engineering disciplines, yes, in the undergraduate population there are more women. But because of the legacy of having fewer women, if you look at the higher level positions, whether it’s in industry or whether it’s the upper levels of the university, like the higher rank, full professors or chair professors and so on, that the numbers certainly would be smaller. But after having women for so many years and large numbers in chemical engineering, you’re starting to see even at the highest levels of achievement, the fraction of women is no longer token one or 2% or 5%.

So just to give you one statistic, the National Academy of Engineering announced the 2023 elections of the new members of the National Academy of Engineers. This is the highest honor that the engineering community can bestow an engineer both in industry and in academia. And by the rules of the academy, fewer than 1% of the engineers can be members, and it’s based on a number of criteria and achievements and so on. So it turns out there are two chemical engineering alums in this class of 2023, and both are women.

So we’re not talking about even 40%. We’re talking two out of two, 100%. And I think that’s a message for especially young women who are thinking of engineering that the numbers obviously speak for itself. So definitely I cannot speak for the other branches of engineering since I don’t work in those areas, but certainly in chemical engineering, women who come into chemical engineering, they can look at our success and there’s no shortage of role models, there’s no shortage of success stories, and I think this is the reason why the numbers are basically approaching 50/50.

Kate Young:

Professor Kim has lived in multiple countries and on both the east and west coast in the United States. So why does he continue to stay in Indiana in this Boilermaker community?

Professor Kim:

So I think in general, I am very happy in the Midwest, even though all of my early childhood and education was on the coast in all my jobs, whether academic or industry have been in the Midwest. I’m very comfortable in the Midwest. I think the Midwest has the friendliest of people. I think people are more polite. Life is just better in the Midwest. I actually have two homes. I have an apartment in West Lafayette, but I also have my home in Indianapolis, same place as when I worked at Eli Lilly. And especially now with our big move into Indianapolis presence for Purdue, you hear stories about, well, faculty say, “Well, I don’t want to commute to Indianapolis to teach a class and so on.” Well, I’ve been commuting from Indianapolis to Purdue for the better part of 20 years. And so if I am involved in meetings in Indianapolis or teaching in Indianapolis, that actually means a shorter commute for me.

Kate Young:

I asked Professor Kim what his favorite part of being a Boilermaker professor is, and I loved his answer for this one.

Professor Kim:

I think the role of an educator and including professor, every day, you’re meeting young people and it also keeps you young. So I actually got my first job as a professor, my offer letter when I was only 23. I started pretty early, and then one day you wake up and you’re no longer in your 20s. That was a long time ago. I’m actually approaching mid-60s now, and so it’s been more than 40 years. But inside me, I am still the same person I was at 23 and interacting with all these young faculty, and they no longer mistake me for a student. But it’s great working with young people and helping them launch successful careers and so on.

Kate Young:

Remember when we discussed land grant universities earlier in this episode? Professor Kim touches on the Purdue culture, which is full of problem solvers. And the advice that he gives, or really the advice he doesn’t have to give Boilermaker students.

Professor Kim:

I’ll always have this short phrase or expression, be part of the solution, not the problem. I almost don’t have to give that advice because that’s also the nature of the Purdue students and graduates. Company after companies say that they really like to recruit our students and hire them because that’s actually what happens. They inevitably are part of the solution rather than creating problems and headaches for their companies. They are doers, they get things done, they accomplish things, and companies just love them. And I think that’s definitely our future as well.

Kate Young:

I asked Professor Kim why he’s proud to be a Boilermaker.

Professor Kim:

Our president, Mung Chang, he coined the phrase, the pinnacle of excellence at scale. For me, that is something that rings especially true because I did my undergraduate at Caltech, which is a great example of excellence at very, very small scale. So if you cherry-pick 200 students only every year, you can create a system where you get very, very good students, exceptional students. They even have the Big Bang Theory comedy about that culture, right?

Kate Young:

Yes.

Professor Kim:

So clearly excellence, but at a very small scale. At the other end of the spectrum, there are large land grant universities where the main philosophy is access. And so obviously the excellence cannot occur when you have such large numbers or so it’s usually believed. But Purdue is this simultaneous combination of scale and excellence. I think for several years in a row now, we’ve been ranked as one of the top five college of engineering, and yet among those top five highly ranked colleges of engineering, we are the only one in the top 10 in terms of size. So if you consider simultaneously the scale in which we operate and the excellence, that’s pretty rare, and I think I’m very proud of Purdue’s distinction in that regard.

Kate Young:

Professor Kim ends our conversation with his admiration for Purdue Global. Purdue University’s accredited and affordable online solution designed for the working adult with life experience and often some college credit, but no degree.

Professor Kim:

When we think of Purdue, obviously we think of our historic campus here in West Lafayette. I think, and even though we will continue to excel and do our best, I think what we have done in terms of adult education and giving people a second chance, I think that is the strength of the United States. In many countries in the world, you are steered on a certain path at a very young age. If you don’t get to the right pre-K or the right kindergarten or the right elementary school, you’re doomed and your fate is sealed. But this nation is a nation of multiple chances and people who persevere can do whatever they want. And so you think about the large numbers of people who didn’t have, for whatever reason, didn’t have the opportunity to get a college degree.

And I think Purdue Global is probably one of the boldest things that have happened in the world of land grant universities in the past decade, maybe in the past half a century. And it is an experiment that’s ongoing, but already we’re starting to see exceptional stories of young people and adults, mid-career people whose lives have been transformed by that additional chance to get that college degree. And I think we should be very proud of that. And in the future, I think the original Purdue, the land grant University, with its original mission and this new challenge of incorporating more adults into the higher education world, we will find new ways and new paths to greatness.

Kate Young:

That’s incredible. And by the way, if you haven’t listened to our incredible This Is Purdue episode with Purdue Global Chancellor Frank Dooley yet, I recommend checking that out to learn more about Purdue Global. We can’t thank Professor Kim enough for his time in sharing those stories with us. Head over to our podcast YouTube page, youtube.com/@thisispurdue to watch our video clips from his interview. And remember, follow us on your favorite podcast platform, including YouTube to never miss an episode.

This Is Purdue is hosted and written by me, Kate Young. At this special podcast shoot during the annual President’s Council weekend in Naples, Florida, our podcast team consisted of Ted Shellenberger, Jon Garcia, Becky Rubinos, and Trevor Peters. Our social media marketing is led by Ashley Shroyer and Maria Welch. Our podcast distribution is led by Theresa Walker and Carly Eastman. Our podcast design is led by Caitlin Freeville.

Our podcast team project manager is Rain Gu. Our podcast YouTube promotion is managed by Megan Hoskins and Kirsten Bowman. Additional writing assistance is led by Joel Meredith, and podcast research is led by Sophie Ritz. Thanks for listening to This Is Purdue. For more information on this episode, visit our website at purdue.edu/podcasts. There you can head over to your favorite podcast app to subscribe and leave us a review. And as always, boiler up.