‘Life is too short for a boring career’

At 50, fun-loving Patti Bertolino says Purdue Global redeemed her opportunity to earn the master’s degree she always wanted.

Patti Bertolino (MS instructional design ’24, Purdue Global) is never boring. She really hates boring.

Her favorite leisure activities are all excitement — she likes to ski. She scuba dives. She travels. So when it comes to her career, why shouldn’t that be exciting, too?

In particular, she’s passionate about making learning fun, so designing the instruction for corporate training sessions was a perfect fit. But as she neared 50 and a post-COVID-19 world started to see cutbacks and layoffs in the corporate sector, she wanted stability.

As much as Bertolino lives for excitement, wondering whether she’d be able to continue on her path if layoffs came around was not what she had in mind. She knew that gaining an edge over the competition would have to involve earning a master’s degree.

“A master’s gives me authority as a subject matter expert,” she says. “It’s a well-respected credential that will help me stand out if I’m ever in the position of searching for a new job.”

Freshly graduated from Purdue Global, she reflects on how her online master’s changed everything.

Making learning fun as an instructional designer

It was during a staff training session when she was new to corporate America that her mind started to wander. She fantasized about how she’d make the session fun. How could it be interactive? How would she get people excited about the information?

Her career was born in that moment.

“I realized I wanted to be the person in front of the room,” she says. “I’m eager to learn, but I’m also eager not to be bored! So I became a trainer for a national financial services corporation. It was a very high-traffic training situation because mortgage rates would go down — we’d hire 500 people. A new law would get passed — we’d hire 400 more.”

Before she knew it, she was teaching thousands at a time at a well-respected corporation, learning everything she could from YouTube and reading books. She was making escape rooms. She was modeling trainings after “The Amazing Race.” In every way, Bertolino was killing it.

As she continued down this path, the next step seemed to be an advanced degree. Her company was covering tuition for employees, and Bertolino says it couldn’t have been a more accessible setup.

“We had tuition reimbursement. They literally came to our building and taught classes. It was almost a no-brainer,” she says.

It was so reachable, in fact, that it was easy to take the opportunity for granted. She’d do it someday.

But time ran out.

The professors really let me be me on the discussion boards. … I was one of the few who already works in corporate. They allowed me to share (my experience) with my peers in class.

Patti Bertolino

MS instructional design technology ’24, Purdue Global

A missed opportunity

In 2018 the company Bertolino had worked at for 20 years was bought. Employees who designed curriculum were among the first to be laid off. On top of the upheaval and emotional devastation, there was regret over the degree she never got.

“It would have been so easy. It was right there!” she says.

Finding another job wasn’t easy, but eventually she began doing what she loved again at another prominent financial institution. Unfortunately, four years later, in a post-COVID-19 economy, that company had to shutter its doors, and she was in the job market once again.

She was rattled. With layoffs becoming more and more common, she had to do something to secure her place in the field she loved. And she couldn’t help but remember that she’d once had the chance to make herself stand out.

But rather than wallow in that mistake, Bertolino vowed not to make it again.

“It really shook me,” she says. “When I was hired at Prudential, I thought, ‘This time, I’m getting a master’s degree.’ I wasn’t going to let an opportunity like that slip away again.”

An online education to stabilize the future

“I picked Purdue Global because companies are moving into a more global, work-at-home scenario. There were local options, but everybody’s heard of Purdue,” she says.

Bertolino found that her classes didn’t just teach her what works in her job — she already had a strong knowledge base from her 20 years of experience — but she learned why her techniques worked.

“I got to learn the theory behind many of the practices I’ve been using for years, and it gives me credibility,” she says.

During her experience as a Purdue Global student, she also felt respected for the wisdom she’d already earned in the field.

“The professors really let me be me on the discussion boards,” she says. “A lot of the people in my class were teachers who wanted to move to a corporate model because of COVID. I was one of the few who already works in corporate. They allowed me to share ways I engage my audience with my peers in class.”

And now that she has her degree in hand, she hopes when others hear her story, they’ll know their limitations might not be as limiting as they think.

“I want to inspire others because sometimes people think they can’t go back because they have a baby, or they’re not in their twenties anymore, or they work full time. I tell them, ‘No, you can! I’m 50!’” she says. “It’s never too late to learn.”

Companies are moving into a more global, work-at-home scenario. There were local options, but everybody’s heard of Purdue.

Patti Bertolino MS instructional design technology ’24, Purdue Global

Boilermaker Olympians on the world stage

(Editor’s note, Aug. 11: Former Purdue All-American Annie Drews became a back-to-back Olympic medalist on Sunday when her U.S. team claimed a silver medal in women’s volleyball, having previously won gold in the Tokyo Games. Drews was one of 12 Boilermakers competing in Paris, a group that also included two sixth-place finishers (Devynne Charlton in the women’s 100-meter hurdles and Chukwuebuka Enekwechi in the men’s shot put) and an eighth-place result in 3-meter synchronized diving by Tyler Downs and Greg Duncan. Meanwhile, a trio of Purdue divers — Daryn Wright (19th place), Jaye Patrick (22nd) and Maycey Vieta (24th) — competed in the women’s 10-meter platform; diver Brandon Loschiavo took 17th in the men’s 10-meter platform; incoming graduate transfer swimmer Matheo Mateos placed 20th for Paraguay in the men’s 200-meter individual medley; swimming alumnus Nikola Aćin competed on the Serbian team that placed 11th in the 4×100 freestyle relay; and South African Paula Reto tied for 44th in women’s golf.)

No matter how you measure it, experience served as a teacher for the Purdue athletes participating in the Paris Summer Olympics.

In diving, the sport of four current Boilermakers, there was the added benefit of having four-time medalist David Boudia as an assistant coach of Team USA.

“I don’t know if it is cooler to make it as an athlete or watch someone make it,” said Boudia, who is in his fourth year as a coach with the Boilermaker diving program and who recently took over the head coaching position when Adam Soldati stepped down for health reasons. “Anytime you go to an event at this level, the athletes who will have success are the ones that can control (what is going on in) their heads. I love working with them on that part of the sport.”

And Boudia’s message is resonating. Maycey Vieta was the first to qualify, competing for Puerto Rico and assuring Purdue was represented in diving for the fifth straight Olympics. She has been in several international championship events, but this was her first time at the quadrennial showcase.

“My goal is pretty simple; I want to execute my cues on all five dives,” Vieta said prior to leaving for Paris. “That is what Dave and I have worked on. These are the same five dives I have done (in competitions) for the last four years.”

It was a bigger stage, to be sure, but it was also about having the mind lead the body into flawless execution.

While Boudia coached Vieta at the Games, it was also extra special for her to have support from Boilermaker teammates Daryn Wright (representing the U.S.) and Jaye Patrick (Latvia) while the trio competed in the 10-meter platform event. (And to be proposed to by fellow Boilermaker Olympic diver Greg Duncan in Paris).

“It feels like home having all the Purdue divers in Paris,” Vieta said. “It is very comforting to have all my teammates there. Dave and Adam warned us that it would be a new experience and, at times, emotionally exhausting because of other events like the opening ceremonies. Still, we will represent our country, which is the focus.”

It feels like home having all the Purdue divers in Paris.

Maycey vieta, former purdue diver (2020-24)

Boudia, who will help coach Brandon Loschiavo on 10-meter on Friday, also worked with Duncan and Tyler Downs in the 3-meter synchronized event. Duncan is a four-time All-American and teamed with Downs, who spent a year at Purdue and won the 2022 NCAA title on platform.

Loschiavo did not learn he had qualified until a day before the opening ceremony when a quota spot opened up late for diving. Like Wright, he had finished as the runner-up on 10-meter at the U.S. Olympic Team Trials in June.

Downs and Loschiavo competed in the Tokyo Olympics three years ago, while Duncan, age 25, made his first appearance on the world’s biggest athletic stage.

“This team (at Purdue) is built with Olympians and those that treat the sport with respect,” said Duncan, who admitted he would rely on his diving partner’s previous Olympic experience. “If we do what we are expected to do, it will turn out great.”

Although all of the divers except Downs were first-time Olympians, all are veterans of elite international competition. Wright (20) is the youngest and Downs turned 21 in mid-July.

Patrick began her collegiate career at Northwestern before spending her fifth year as a graduate student training at the Morgan J. Burke Aquatic Center under Soldati and Boudia. She credited Boudia for convincing her to continue her career after she competed for Latvia at the 2023 World Aquatics Championships in Japan.

“I was always realistic, thinking, ‘No, this can’t be me who will make it to the Olympics,’ especially since I started so late,” Patrick said. “Dave said, ‘You are not done yet; we will work on this and get you to the Olympics.’ So it became a realistic dream of mine about a year ago. He worked on the mental approach, and it changed everything.”

When Patrick arrived in the City of Light, her approach was simple. “I want to keep my head on straight and do my best,” she said. “I used to be alone at international competitions in past years, but now I have teammates and coaches (that I know). It means so much.”

Wright said Boudia and Soldati’s approach to the mental aspect also helped her earn a spot on Team USA. And she utilized their “one day at a time” approach when the competition began. Especially after some heartbreak in past international competitions.

“(The Olympics) is the same thing I have done for a long time,” Wright said. “It just has a fancy name attached to it.”

Experience also permeates Purdue’s non-diving Olympians

Boilermakers Annie Drews, Chukwuebuka Enekwechi, Devynne Charlton, Nikola Aćin and Paula Reto all made their second trip to the Olympic Games.

Drews played a vital role on USA’s first women’s volleyball gold medal team in the Tokyo Games, while Enekwechi looked to improve on his 12th-place finish in the shot put. Charlton had a sixth-place finish in the 100-meter hurdles in the 2020 Olympics, representing the Bahamas. She is now a world record holder in the 60-meter hurdles, traditionally an indoor event. Aćin earned a second trip to the Olympics after being part of Serbia’s victorious 4×100-meter freestyle relay at the European Aquatics Championships in June.

Former Purdue golfer Reto made her second appearance after competing for South Africa in Rio in 2016.

“It is such an accomplishment to have ‘Olympian’ next to your name,” said Reto, a freshman on Purdue’s 2010 national championship team. “It is one dream to get there and another to win something.”

Reto, who has competed on the LPGA Tour since graduating from Purdue in 2013, won’t be able to attend the opening or closing ceremonies as golf takes place in the middle of the Games, sandwiched between LPGA events. But she planned to support her Purdue brethren, even if it was from the stands.

“My goal is to see many other sports and other Purdue athletes perform in Paris,” Reto said. “I fondly remember cheering David on in Rio.

“Purdue changed my life,” she added. “We had such a great coach in Devon Brouse. Everything we had at Purdue was in top shape, and I love that the tradition of athletics excellence lives on at the Olympic Games.”

Boilermaker gold in past summer games

Purdue has been a frequent participant in the Summer Games and has had success, winning 14 gold medals, seven silver medals and six bronze medals.

Ray Ewry’s 10 gold medals in the standing high jump and long jump from 1900-08 boosted the school’s medal totals. Purdue went without a medal for the next nine Olympiads before swimmer Keith Carter won a silver in the 200-meter breaststroke in London in 1948. Four years later, Coach Richard “Pappy” Papenguth coached the U.S. women’s swimming and diving team. Papenguth led the Boilermaker swimming program until 1969.

Howie Williams (1952) and Terry Dischinger (1960) are the lone Boilermaker men’s basketball players who earned medals (both gold). Fifty-two years later, David Boudia dramatically brought home the gold in 10-meter diving in London. Amanda Elmore became the first Boilermaker woman to win gold. Elmore won it in rowing in 2016, followed by Annie Drews in volleyball in 2020.

Purdue’s participation in the Summer Games in the 21st century is by far its most remarkable run of success since the modern Games began in 1896. In total, 55 athletes with Purdue ties have competed since summer competition began, 31 since 2000.

Written by Alan Karpick, publisher of GoldandBlack.com since 1996.

2024 Boilermaker Olympians (years at Purdue)

- Nikola Aćin, Swimming (2019-22) — Serbia (placed 11th in 4×100 freestyle relay)

- Devynne Charlton, Track & Field (2014-17) — The Bahamas (placed sixth in 100m hurdles)

- Tyler Downs, Diving (2021-22) — USA (placed eighth in 3m synchronized springboard with Greg Duncan)

- Annie Drews, Volleyball (2012-15) — USA (team won silver medal)

- Greg Duncan, Diving (2019-22) — USA (placed eighth in 3m synchronized springboard with Tyler Downs)

- Chukwuebuka Enekwechi, Track & Field (2012-16) — Nigeria (placed sixth in shot put)

- Brandon Loschiavo, Diving (2016-21) — USA (placed 17th in men’s 10m platform)

- Matheo Mateos, Swimming (incoming graduate transfer) — Paraguay (placed 20th in the men’s 200m individual medley)

- Jaye Patrick, Diving (2024) — Latvia (placed 22nd in women’s 10m platform)

- Paula Reto, Golf (2010-13) — South Africa (tied for 44th in women’s golf)

- Maycey Vieta, Diving (2020-24) — Puerto Rico (placed 24th in women’s 10m platform)

- Daryn Wright, Diving (2022-) — USA (placed 19th in women’s 10m platform)

2024 Boilermaker Paralympians (years at Purdue), the Paralympic Games begin Aug. 28

- Evan Austin, Swimming (volunteer assistant coach 2019-22, currently trains at the Burke Aquatic Center) — USA

- Joel Gomez, Track & Field (2023-) — USA

Guild partnership with Team USA has athlete chasing down the next dream

This four-time U.S. Paralympian and Purdue Global student looks toward a future that includes a master’s degree in education.

Focus.

Drive.

Determination.

Strength.

You’d expect to be able to describe any elite athlete with these words, and four-time U.S. Paralympian Rose Hollermann exudes all of them. But perhaps one thing that’s visible in her face, her body language and how she speaks is a trait that makes her exceptional on a completely different plane — something that may be surprising to see in someone who has suffered so much.

Joy.

When she was 5, Hollermann, along with her mom and three older brothers — Seth, Shane and Ethan — were in a car accident that partially paralyzed Rose from the waist down and claimed the lives of Shane and Ethan.

“When something really bad happens to you, you’re sad for a while. You grieve. After a long time, that first moment you feel happy again …” She pauses, searching for words to describe it.

“That kind of happiness is really hard to describe. It’s like a breath of fresh air. It’s intense. You’ve seen how bad things can be, and it makes you appreciate more.”

As she worked toward functionally walking again, 5-year-old Rose participated in adaptive swimming and soon went competitive with it. Then, she couldn’t be stopped. She tried sled hockey, archery, tennis, cross-country skiing, and track and field sports. But when she discovered wheelchair basketball, she found family.

“I have a hard time calling it work,” she says. “I think if you’re doing something you like, then it isn’t work. It’s something more joyful than that. Finding things I’m passionate about really motivates me.”

It has motivated her all the way to the top of her sport. At 15, she became the youngest person to qualify for the national team. She competed in her first Paralympics in London in 2012. She came back to win gold in 2016 at the Rio Games, and then for yet another round in the Tokyo 2020 Games, where she helped lead a young, completely new team to the bronze. Now, she’s on her way to her fourth Paralympics appearance in Paris.

But her plans don’t end there. She’s seeing a future beyond basketball — one helping kids find their happiness, just like the volunteers in her community who helped her after her accident.

“The reason we are who we are as individuals is because of the people who gave back to us. Growing up as a disabled kid, I was surrounded by people who were volunteering. Their time was dedicated just for us to have a little bit of happiness,” she says. “I hope, after basketball, I can spend my life giving back to others, whether it’s being a teacher or working in the sport.”

Team USA and Guild came together at just the right time, then, to inspire Hollermann to earn a master’s degree in education from Purdue Global.

I think as a 5-year-old, realizing that maybe something you thought was taken away from you is actually something you can work really hard to gain back — I think that was a really great lesson for me, and I’ve held onto that.

Rose Hollermann

U.S. Paralympian, Wheelchair Basketball

MS Education

Learning to walk again

Hollermann says it was first thought that her paralysis from the waist down was complete, and there was no hope of walking again.

But in a shocking moment, she confided to her uncle, who sat in the room with her.

“I told him, ‘They’re saying I can’t feel my feet, but I can feel my feet.’”

This sent her uncle chasing down a doctor, who ran more tests and concluded that her spinal cord injury was partial, not complete. It would be possible after all for her to learn to walk again. But it was going to take a lot of hard work.

Although her capacity to walk would be limited (she still uses a wheelchair most of the time because her affected gait has a history of causing her severe knee pain), the mental shift had a profound impact on her young mind.

“I think as a 5-year-old, realizing that something you thought was taken away from you is actually something you can work really hard to gain back — I think that was a really great lesson for me, and I’ve held onto that,” she says.

The long process of relearning to walk and the lessons it taught her carried her through other challenges down the road. She became stubborn. Then she became determined.

“As an adult, looking back at the therapy I had to do to learn to walk again, I learned valuable lessons about putting the physical work into your body to reach a goal,” she says. “Now, as an athlete, it’s something I get to feel every day — setting goals for myself that I can try to reach to become a better player.

“My mom likes to say, ‘If you want Rose to do something, then tell her she can’t.’ When I started wheelchair basketball, I was always the only girl. So just the idea of someone saying, ‘You can’t do that; you’re a girl,’ was something that really motivated me. I wanted to prove that we’re the same.”

But when it came to narrowing her scope to one sport, there was something healing about playing with a team as opposed to competing in individual sports like archery or tennis.

“I really liked basketball because it was a big group of people working together, which was something I’d lost,” she says. “Our family was basically cut in half, and that whole big-family feeling is the thing I miss the most.”

The joy only increased as her training intensified, and she started to have success in her chosen sport. Now, as a member of Team USA, Hollermann says it has the ultimate large family feel to it, especially when she became the youngest on the team at age 15.

“I grew up on the national team. It was my first opportunity to have sisters, and my team really treated me like their little sister. I think the second youngest was 10 years older than me,” she says. “They really brought me under their wing.”

That year at the London Games, Team USA barely missed the podium, finishing in fourth place. But the experience was life-changing, and Hollermann was ready to gain some speed.

But it was the next Paralympics in Rio that would change her relationship with basketball forever.

Gaining speed, facing setbacks and moving Team USA forward

It was the ultimate win — Hollermann helped Team USA bring home the gold in 2016.

“We won gold in Rio. It’s a dream come true for every athlete; you’re always striving for gold,” she says. But that ultimate high was followed by what felt like an overwhelming challenge.

“In 2016 we had all but three girls retire after the Rio Games, which is something that’s actually really rare in wheelchair basketball,” she says. “In 2020 we brought a really young group of girls, super inexperienced, to the Tokyo Games.”

Hollermann was thrust into leadership on that team, working relentlessly to help each of her teammates maximize their skill set and develop the team chemistry.

“We had to really grind for everything we earned, and that made it really special,” she says. “We ended up winning bronze in Tokyo, and it felt really great, knowing how much work we put into it. I think we put more work into the bronze medal than we did the gold just because we came from so far behind. We had to learn and grow together to get to that position.”

In 2019, while training for the Tokyo Games, Hollermann earned her bachelor’s degree in elementary education and was almost simultaneously presented the opportunity to earn her master’s — a one-year-only offer.

“I thought going abroad for the first time and playing professionally, I would be too overwhelmed to be taking classes on top of that,” she says. “I always regretted it because I just didn’t get the opportunity again.”

But when she took a trip to Japan to visit a college friend, she started reconsidering.

“My friend was from Japan and got his master’s in the States. When he went back to Japan, he started a program for adaptive sports. During my visit, you could see how much his master’s degree helped, how much he was able to do with it. Having that real-life experience, seeing him thriving, I was ready to start exploring options,” she says.

That’s when the opportunity of a lifetime landed in her email.

Chasing dreams at full speed with Purdue Global

“Instantly” is the best way to describe how Hollermann responded to the email announcement that Team USA was partnering with Guild to provide athletes with the educational opportunities they needed to build a future after sports.

“As soon as I read the email, I applied immediately,” she says. “I’d been waiting for something like this.”

And her experience with Purdue Global has already shown that it will go above and beyond for its students.

“Already, the process with my advisor has been really good with getting set up. When I was applying for my bachelor’s with other universities, I didn’t have quite such an interactive experience with that person as I have with Purdue Global,” she says. And the online platform, to her, makes all the difference in making her return to classes an attainable goal.

“As Olympians and Paralympians, we dedicate our lives to something that’s a short-term thing. We’re spending countless hours on a sport where retirement comes at such a young age. So you have to be prepared for what’s next after that point, but there’s not many hours in the day to fit it in,” she says. “It’s great to have a platform that’s flexible and inexpensive for us.”

For Hollermann, the future with her team and beyond is taking clearer shape. But first, the Paris Games are upcoming, and she’s ready to bring home some hardware.

“Basketball is growing so much, and it’s in a unique position where it’s more competitive than it’s ever been before,” she says. “So going to this Paralympics, of course we always want to win golds. We want to have something shiny wrapped around our necks at the end of it. But I think Team USA is in a really great position to be able to do that this year. The team is so deep, so competitive, and we’re really looking forward to the Paralympic Games.”

In the meantime, Purdue Global is there, so she’ll be ready to chase what’s next. It’s all joy, and she can’t wait to pass it on to others.

“There are a lot of dreams outside of basketball. I want to have a family and a house and live a happy life,” she says. “As a disabled female athlete, I’ve had a lot of moments of insecurity. I hope that being entirely myself and being confident in who I am gives other girls the ability to be confident and happy in their own skin, too.”

If you’re doing something you like, then it isn’t work. It’s something more joyful than that.

Rose Hollermann U.S. Paralympian, Wheelchair Basketball

MS Education

Boilermakers Beyond Borders: a transformative trip to Costa Rica

Purdue student-athletes, staffers travel abroad to build athletics court for underserved youth

The mission is simple. It couldn’t be any more straightforward.

“Transforming lives through building courts and cultural exchange.”

It states that right on the Courts for Kids website. But it begs the question, whose life is being transformed? Is it the Costa Rican kids the Boilermakers Beyond Borders group served by helping construct a concrete basketball court in early June? Or is it the 15-member party that represented Purdue Athletics in the Central American country?

“This experience will stick with me forever,” distance runner Geno Christofanelli says. “We learned that so much can be done when communities work together.”

Boilermakers Beyond Borders is a recently formed international travel program for Purdue student-athletes and staff made possible under the John Purdue Club’s Forging Ahead campaign. The program allows Boilermaker student-athletes to give back and expand their worldview through a mission trip benefitting local youth in an underdeveloped country.

This week-long experience wasn’t easy for the Purdue crew. It was stifling hot, the work hours were long and sometimes a bit chaotic, and accommodations were far from luxurious – yet it didn’t seem to matter.

The Purdue contingent provided labor, ranging from clearing rocks from the area to hauling water buckets and cinder blocks.

“It was hard, I am not going to lie,” says Amiyah Reynolds, a member of the women’s basketball team. “To the Costa Rican workers, it was nothing, but we needed breaks, lots of breaks.

“There were ants and bugs, and we slept on the floor. The fact that the locals lived in that and were OK with it taught me a lot. They were energetic and were fighting for a spot to help us.”

Reynolds said that the locals would race home from their work at the local banana processing factory to get involved, and the kids would do the same when they came home from school. They were all simply happy to pitch in.

Transforming the dirt square into a playing surface took most of the week. The locals eagerly worked alongside the Purdue group, and despite the language barrier, the common thread was finishing the court.

“It was like a team bucket brigade,” says Logan Sandlin, a decathlete for the Boilermakers and recent graduate. “A big takeaway for us is you don’t have to plan everything for it to go well.”

With the work, the locals expressed joy and plenty of it. They worked past dusk most nights, using flashlights to get the job done.

“Life is simple there, but the people seem so happy,” Christofanelli says. “They aren’t at all hung up on the things that we as Americans seem to be, and that was a teaching moment for all of us.”

And the cultural experience came from many different facets of the trip.

“The food was awesome,” Christofanelli says. “We had rice and beans for 21 meals, but it was different and delicious every time. And the fresh fruit was like nothing I have ever had.”

Boilermakers Beyond Borders was, in part, the idea of Kelli Briscoe and Candace Britten, who serve as assistant directors in student-athlete development. The duo also made the trip. After attending a conference, the pair earned support from the athletics department senior staff after submitting a proposal.

Funding for the group’s approximately $35,000 for travel and lodging came via crowdfunding and from the John Purdue Club. Britten says one of the challenges was finding a time when Purdue’s busy student-athletes could go.

“Our job is to help our student-athletes prepare for the real world,” Britten says. “Sometimes they are focused so much on their sport that they don’t see anything past their bubble. Many of our sports don’t have an opportunity for international travel, so this brings it to them. I am a big believer that it is part of a well-rounded experience.”

A common refrain from these Boilermakers was that they gained more from the experience than they put in.

“I got so much out of the trip, but what was special for me was the time spent with our student-athletes,” Britten says. “We had absolutely zero issues. This trip provided memories that will last a lifetime, unforgettable memories. Knowing that Kelli and I helped make that happen is very satisfying.”

Reynolds, who admits to being very introverted, summed up the experience of her fellow student-athletes.

‘It was the most I have ever danced,” says Reynolds, who had a brief opportunity to impart her hoops skills to the children. “Even at 9 p.m., they were blasting music. It got me through those long seven days.

“But it was also so important that I learned about the lives of my fellow athletes at Purdue. I didn’t know their names when we first started preparing for the trip, but by the time we got back home, I felt like we were lifelong friends.”

The group’s experience with the community’s children undoubtedly left an indelible mark.

“The most fun part of it was playing and interacting with the kids,” Sandlin says. “I am so bad at soccer, but it didn’t matter. It was great to connect with them physically, even if we didn’t speak the language. It helped bridge all gaps.”

For Christofanelli, it made him proud to be at Purdue.

“It was great to bond with other Purdue student-athletes, and the experience really embodied what it means to be a Boilermaker,” he says.

In the end, it was about hard work and giving back. But it was also about having fun in an experience that will last a lifetime.

By Alan Karpick, publisher of GoldandBlack.com since 1996.

‘Purdue Global made my dream job possible’

This Purdue Extension educator says an online master’s degree in health education got her exactly where she wanted to go

When someone is trying to make a life change in nutrition or fitness, those who are there to guide often say to “trust the process.” Follow the plan; see results. But because the work is outside a person’s comfort zone, it’s a common experience to lose faith, to wonder if all the hard work is going to accomplish what it promises.

As someone who has spent her whole adult life in the health and wellness industry, Mandy Gray (BS health education ’21, MS health education ’23, Purdue Global) has seen the evidence countless times that food and exercise can heal and prevent disease. Over the years, it’s become second nature to her to trust that process.

“Public health is a huge passion of mine,” she says. “I was a personal trainer for a long time, and I really wanted to try to help people understand that there are so many things we can do to keep our bodies healthy — with nutrition, movement, exercise, mental health. We can prevent disease instead of being reactive.”

But “trusting the process” wasn’t easy in every area of her life.

When she started her bachelor’s degree in 1996, she got two years in before she felt burned out. Having made it halfway through, she found a way to get an associate degree out of the time she put in.

“Finishing the four-year degree was always in the back of my head,” she says. “But I had my first child in 2001, and I thought there was no way I could go back now that I had a baby.”

Once she’d raised that child and then a second one into their school-age years, she decided she wanted to work outside her home part time. And she found the perfect fit as a nutrition education program advisor with Purdue Extension.

“I loved what I did — it was community education,” she says. “I knew this was my thing. But I felt like I could do more. I started classes with Purdue Global as a NEPA because I couldn’t move forward from that with an associate degree, and the job I was really dreaming about required a master’s.”

It would have been easy for her to look at her dream job, recently filled by a qualified person, and decide it wouldn’t be worth it to start a yearslong process to become qualified for it herself. But Gray went in another direction — she decided to have faith that starting the journey toward her bachelor’s and eventually her master’s degrees would lead to the right opportunity for her and her family.

Setting up a comeback with Purdue Global

Even from the start of her role as a nutrition education program advisor, Gray had her eye on a role a little higher up — a Purdue Extension educator — that would give her more autonomy over designing and teaching programs.

“I loved what I did as a NEPA, but I wanted to be able to do more community health programs, and I wanted to stay in my county,” she says. “Extension educators are allowed to teach programs in any single area you can think of that falls under the health and wellness umbrella. It even opens up opportunities for different types of certifications.”

There was no promise — in fact, it was unlikely — that the exact job she wanted would be available at the end of the exact number of years she needed to earn the qualifying degrees. But she had faith in the power of education.

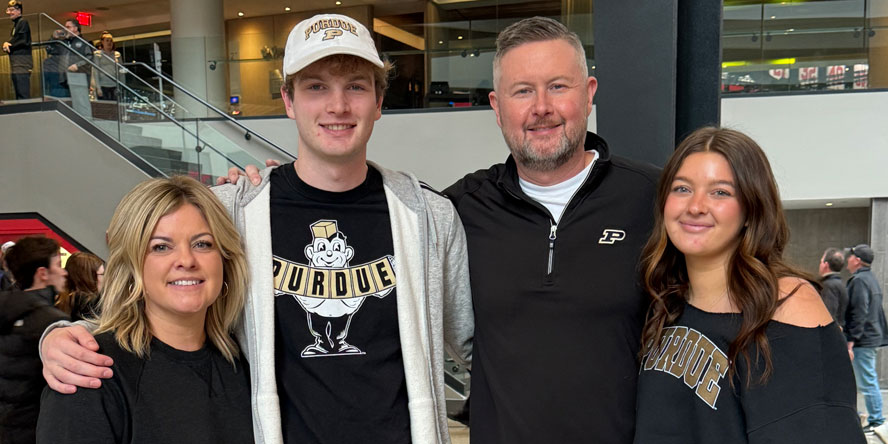

Then it was a matter of figuring out how she could make that process work for her family. When she found an online option through Purdue Global, the pieces slid into place.

“We’re a Purdue family, through and through. We’ve all gone to Purdue — my kids are at Purdue, my husband graduated from Purdue,” she says. “It was doable, first of all, because it was all online. I could do my classes from anywhere in the world. I could be present for class if we were on vacation, or if I was on the way to a volleyball or a baseball game. I could still be a part of everything my family was doing,” she says.

“I never missed any important moments — ever. I remember going on vacation during my kids’ spring break. Some of the group went to dinner and I said to them, ‘I have a seminar I really can’t miss, but I’ll be here when you get back.’ I may have missed out on a dinner or two, but I still got to go on those trips.”

She finished her bachelor’s degree in 2021. But she still had her eye on the dream job, and that would require a master’s.

I never missed any important moments — ever.

Mandy Gray

BS health education ’21, Purdue Global

MS health education ’23, Purdue Global

A master’s in health education pays off

The Extension educator role in her county wasn’t an open position, but Gray decided to trust the process of setting herself up for the right opportunity. She would continue with Purdue Global and work toward that master’s degree.

“When I was working as a NEPA, someone new had just taken over the Extension educator role in my county. I thought the chances of the job opening up anytime soon were zero. I thought she’d retire from there,” she says.

Halfway through, the unthinkable happened.

About a year before she was due to complete her master’s, she got a phone call. The person who was currently in the job Gray wanted had decided to move on to a different opportunity, and she wanted Gray to have the first swing at it.

“She said, ‘I know you’re close; you’re already working on your master’s degree, so they’ll let you apply.’ I couldn’t think straight!” she says.

“I went through the interview process, and I got it,” she continues. “I wanted it forever. I’ve been promoted a few times since then, and I absolutely love what I’m doing.”

Now Gray looks at her experience as an adult student and says that, while she can’t promise others will be presented with the unicorn of a job she was, she’s proud that she took the steps she did. If she’d banked on the odds and decided against earning her master’s degree, she would have missed the opportunity of a lifetime.

“I don’t do the same thing every day,” she says. “I can teach mental health first aid today. Then I can go teach a ServSafe class tomorrow. The sky’s the limit. With the education I got from Purdue Global, I am able to create the programs I want because I have the training and education behind me. I know how to do that now.

“And I cheer my colleagues on, too. At least five of my colleagues are taking Purdue Global classes right now. I get to help motivate them and cheer them on.”

With the education I got from Purdue Global, I am able to create the programs I want because I have the training and education behind me.

Mandy Gray BS health education ’21, Purdue Global

MS health education ’23, Purdue Global

The path from Nigeria to a future in medicine in the U.S.

Get to know Sade Adeojo and how she achieved her childhood dream with Purdue Global.

Sade Adeojo moved from Nigeria to the U.S. in 1996. From working two jobs to earning a Purdue Global degree, Adeojo’s story is one of resilience and determination, fueled by her passion to help others.

Growing up in Nigeria, Sade always had one goal in mind — to become a doctor.

“I always wanted to be in the medical field. It’s always been my passion,” she says.

As she grew into a young adult, her goal remained the same. In Nigeria, she took some college classes in science technology, which proved to be only her first step in higher education. What she didn’t know at the time is that with Purdue Global’s support, she would go on to earn her nurse practitioner certificate.

“Ever since I was in elementary school, I have always told myself, ‘I’m going to be a doctor,’” she says.

Ever since I was in elementary school, I was always telling myself, ‘I’m going to be a doctor.’

Sade Adeojo

Doctor of Nursing Practice, Purdue Global ’18

From Nigeria to New York

When Adeojo decided to move to the United States in 1996, she knew it would take a lot of hard work to reach that goal of becoming a doctor. In New York, she was putting in long hours working two jobs as a cashier at a 99 cent store and Burger King. The hope of going back to school kept her going during the long days and nights working for minimum wage. And the whole time, she was also busy teaching herself how to live in an entirely new country.

“When I first came to this country, it was a challenge for me to navigate,” she says. “I was able to overcome that culture shock and embark on my academic journey, and I love it here.”

After taking the time to acclimate to her new home, she was ready to go back to school. Not quite sure where to start, she took the first step toward medical school by earning her bachelor’s degree in biology. After she got married and became a mom, she didn’t want to overburden herself by going right into medical school, so she put her dreams on hold. She chose instead to join the medical field by becoming a nurse. That allowed her to keep that same passion for helping others and give her family the best version of herself.

In 2013, after years of working as a bedside nurse, Adeojo was looking for a way to open a new door in the medical field. Her friend told her about Purdue Global’s family nurse practitioner certificate. This was a chance for her to use her years of experience as a nurse to move forward. She graduated from the program two years later but didn’t want to stop there. Her thirst for learning had barely been quenched and, after all, that childhood dream of becoming a doctor hadn’t disappeared yet. That original goal was still lingering in her mind and, with Purdue Global, she finally realized it wasn’t a distant wish. It was possible.

“In 2016, not long after I graduated, I wanted to go back. My goal was always to become a doctor, and at Purdue Global, I saw that it was an option for me,” she says.

She jumped right back into school, earning her doctor of nursing practice (DNP) from Purdue Global. And by 2018, she had the doctorate she had always wanted.

Let nothing stop you from going to school and becoming the best you can be. I encourage people to always move forward.

Sade Adeojo Doctor of Nursing Practice, Purdue Global ’18

Life after earning her DNP

With her DNP finally in hand, Adeojo knew she could start enacting real change in people’s lives. She now works in Pennsylvania as a family nurse practitioner. She’s grateful for how Purdue Global prepared her for this next big step.

“Purdue Global provided the background to be able to start my practice as a nurse practitioner and to be able to care for my patients,” she says. “I learned a lot and it prepared me for what I’m doing now.”

She says her favorite part of her job is being able to recognize the medical problem a patient is having, give them a treatment plan and, when they come back to her, see them happy and healthy. Nothing makes her happier than noticing her patients’ lives have improved in some way after she treats them.

“I love the ability to take care of my patients. When people come back and tell me I helped them or I see a review that says how knowledgeable I am, that makes me so happy,” she says.

But as her number of patients grew, Adeojo realized she needed to offer a new kind of care. She noticed that many of her patients needed psychiatric help, which, with her current skill set, she couldn’t offer. She wished she could help them all in one place, without having to refer them to another clinic. She became determined to earn her psychiatric certification so that instead of referring those patients to someone else, she could help them immediately.

“I started seeing patients that had medical needs, but some of them, I noticed that they have psych issues as well,” Adeojo says. “I said to myself, ‘Let me just go back to school and get my psych certification so that instead of referring those patients, I can see them in my clinic.’”

For a lot of her patients, finding another clinic to treat mental health needs added stress and Adeojo wanted to be able to help. She wanted to be sure that people had access to the same quality of psychiatric care as they had with medical care. Once again, she went back to Purdue Global.

With her postgraduate psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner certificate, she’s excited that she can now expand her clinic to offer additional services.

“It is very important to me because I love to take care of my patients. It has always been my passion,” she says, beaming with joy. “I love what I do in the medical field, and I see that a lot of people need help mentally and emotionally as well. I know I have what it takes to be able to provide that kind of care that they need.”

A legacy of education

Beyond her patients and her practice, Adeojo’s educational journey is also important in the paths of people closer to home.

Taking inspiration from her mom, Adeojo’s daughter graduated from her undergraduate program and was shortly thereafter admitted to a doctorate of psychology program. In fact, two of her three kids have dreams of becoming doctors.

As she’s talking about her children, anyone can tell how much it means to her to see her kids inspired by her passion for education and helping others.

“They see their mom graduating at this age and think, ‘If Mom can do it, I can do it,’” says Adeojo, smiling ear to ear.

“My family was very happy and very supportive of me when I decided to go back to school for more education,” she says. Her husband and kids couldn’t be prouder, but Adeojo says she wishes her dad was here to see this moment.

Her father, who passed away before she graduated high school, always told her to never stop learning. So, she kept his words close to her heart: Never stop learning. This is the legacy of learning that stays alive within her and she is proud to pass on to her kids.

“My dad’s legacy was education, so anywhere he is today, I know he would be so proud of me.”

The dream that became reality

As she thinks about her achievements since moving to the United States in 1996, Adeojo emphasizes the importance of persevering through life’s biggest challenges.

“Never give up. Anything is possible,” she says. “Look what I have accomplished at my age!”

“I was working at Burger King. I was working at a 99 cent store. And now I have a doctoral degree. I am able to practice on my own. So, let nothing stop you from going to school and becoming the best you can be. I encourage people to always move forward,” she says.

Beyond her certificates and degree, she says she is always learning from her family and from her patients. And she is overjoyed to be able to positively impact lives every day as a nurse practitioner.

“I feel fulfilled. I feel happy. This was my goal in life, and I’ve achieved it,” she says.

Adeojo is grateful to her support system for what she has achieved. Her faith, in particular, played an essential role in the confidence she needed to persist.

“My husband is very supportive throughout my educational journey, and I can’t thank him enough. Above all, these achievements in life were made possible through the help of God. He has destined me for what I am today, and I am grateful to my maker for all that he has helped to accomplish.”

What’s in a name? Purdue’s Caitlin Clark follows unique path into Navy

Political science alumna juggled sorority life and Navy ROTC commitment while working to fulfill a childhood dream

Caitlin Clark understands all too well the crowd’s reaction when she crossed the stage to accept her diploma at Purdue’s spring commencement ceremony.

It has been a source of amusement over the last few years that she shares a name with a certain superstar athlete — maybe you’ve heard of her — so the commencement attendees’ murmurs, cheers and laughter when they heard her name called were more of a pleasant surprise than a shock.

“It’s made it funny to have restaurant reservations. People never know who’s going to walk in,” says Clark (BA political science ’24), whose hometown, Carmel, is roughly 15 miles from Gainbridge Fieldhouse in Indianapolis, where the other Caitlin Clark is a rookie on the Indiana Fever. “I have gotten a lot of memes about me being a world-famous basketball player. I get a lot of comments, people striking up conversations when I’m out to dinner or at a store or something like that. It’s been interesting — a little bit more attention than I’d gotten previously.”

While their response was understandable, most commencement attendees were probably unaware that there were good reasons to cheer for the Purdue Caitlin Clark’s achievement. That weekend, she joined both her mother and uncle as Purdue alumni and was commissioned into the U.S. Navy, fulfilling a dream she’s had since she was 8 years old.

An unusual fascination

That’s not an exaggeration. Clark became intrigued with the Navy during early childhood when visiting her aunt and uncle in Annapolis, Maryland, home of the U.S. Naval Academy, and interacting with the midshipmen their family sponsored. Her fascination only grew when interacting with the active-duty and special forces service members she met through her dad’s work providing board certification examinations to U.S. Special Operations Command paramedics.

One Sunday while attending a Catholic Mass at the Naval Academy with her parents, Clark observed the many impressive students decked out in their dress white uniforms and spoke up.

“Caitlin asked, ‘Mom, is this hard?’” recalls her mom, Donna York, recipient of three Purdue nursing degrees: an associate (1980), a bachelor’s (1982) and a Doctor of Nursing Practice (2021). “I said, ‘Oh, I think it’s really hard.’ And then she said, ‘I think this is what I’m going to do. It just seems like the right thing.’ So from that point on, everything was about learning about the Navy.”

Clark’s interest never wavered, right up through participation in Purdue’s Naval ROTC program and her commissioning ceremony as a surface warfare officer two days before commencement.

“I’ve kind of geared everything toward this goal of being in the Navy and being the best officer that I can be and being a leader,” Clark says. “That changed what I did in middle school, what I did in high school, where I ended up. It was very surreal for everything that I’ve been wanting in the last 14 years to finally come to fruition and be an actual naval officer.”

In August, she will report for a basic division officer course ahead of a three-year stint aboard the USS Gravely missile destroyer, followed by a two-year shore tour.

“I can’t really tell you why I’ve always wanted to do it, but I have, and I could not imagine doing anything else,” Clark says. “It’s definitely motivating, and it’s motivating to be surrounded by people that think the same way and want to push for the same things.”

A future intelligence expert?

Clark initially planned to follow both of her parents into the medical profession as a naval doctor. However, she jokes that “my love for biology did not persist” as a college student, causing her to change course.

Instead, she found that the classes in her minor, political science, were what truly excited her. That was especially the case when the subject matter dealt with national security and counterintelligence — starting with a course on terrorism taught by assistant professor of practice Melissa Will.

“She was a CIA analyst before, so she had a crazy-cool perspective,” Clark says of Will. “She is an awesome professor, and I think a lot of that stems from all this knowledge that she has from her past life of not just being in academia.”

In addition to sharing perspectives from more than a decade of intelligence-gathering work, Will invites FBI special agents to her classroom to share their real-world experiences with students. Students are often fascinated by this important work, and Will could tell that was clearly the case during conversations with Clark after class.

Pursuing it as a career is somewhat rare, however, so Will was impressed when Clark accepted an internship with the Department of Justice in the summer of 2023.

“It was great to see she actually got that internship and was able to take those initial steps down that career path,” Will says. “When she came up to talk to me after class, she didn’t specifically say she wanted to do counterintelligence at that point, but she definitely said she was interested in going into the intel track, which was exciting. I hear that a lot, but then she actually was taking steps to do it.”

Clark built upon that foundation through coursework in her minor, French, including an independent study focused on French foreign policy. Working alongside Jessica Sturm, associate professor of French and applied linguistics, Clark selected relevant news articles to analyze, produced papers and infographics, and created a podcast that explained what she learned during the independent study.

Clark’s interest in counterintelligence evolved during her time at Purdue, to the extent that she now hopes to pursue a master’s degree in the discipline once her three years aboard the Gravely come to an end.

“I feel like I really found my niche,” Clark says. “I wish that I had done it earlier.”

Unexpected extracurricular activity

Clark believes many different aspects of her Purdue experience prepared her for the journey ahead in the Navy.

The ROTC program imparted valuable lessons about confidence, toughness and teamwork to be sure.

“She’s always been confident, but now she knows that if she needs to run 20 miles, she’s going to run 20 miles,” York says. “Nothing is insurmountable, and that’s what I think ROTC helped her see. There wasn’t anything she couldn’t do if she really put her mind to it with the right team.”

Meanwhile, participation in another campus activity — membership in Kappa Delta sorority, which her mom describes as “a juxtaposition that you don’t expect” — sharpened other necessary life skills.

“Kappa Delta taught me a lot about living with the people that you’re leading and living where you work, which I think is going to be incredibly valuable when I’m on my ship in the middle of the ocean,” Clark says.

Clark pledged Kappa Delta at the University of Pittsburgh before transferring to Purdue at the end of a COVID-impacted freshman year where she did not attend a single in-person class and campus de-densification efforts had her living in a hotel room instead of a dorm.

She quickly found a home and community at Purdue’s Theta Nu chapter, which she eventually served as chapter president. Although she was one of only three Boilermaker women who were involved in both the Greek system and Navy ROTC, Clark calls the unusual combination a formative experience that helped her recognize the necessity of employing different communication styles when interacting with two extremely different audiences.

“There’s a switch that you have to make,” Clark says. “The feedback you give to someone in an ROTC setting is entirely different than when interacting with a sorority sister.”

Kappa Delta taught me a lot about living with the people that you’re leading and living where you work, which I think is going to be incredibly valuable when I’m on my ship in the middle of the ocean.

Caitlin Clark, a future surface warfare officer on the USS Gravely

‘Find what makes your soul sing’

Clark’s Purdue journey was unique to say the least, but she looks back and can’t imagine doing it any other way.

She took the steps necessary to fulfill a childhood dream and was exposed to subject matter that could become the focus of her career in the Navy and beyond — and she did it her own way.

“Her dad and I really tried to raise her in a way that we want you to find what makes your soul sing and do it. There’s nothing you can’t do,” York says.

Clark has certainly accepted her parents’ challenge thus far, culminating in the commissioning and commencement doubleheader, which just so happened to occur on Mother’s Day weekend.

“It was like blowing up all your firecrackers all at once,” York says. “It was just amazing.”

Throughout Clark’s time at Purdue, fellow students would marvel at the mettle and time-management skills that were necessary to juggle her military regimen, academic coursework and sorority life. But she pulled it off, providing a template for how students can find ways to make time for the things they love to do. “I feel like I got two totally different experiences that have really helped me become a more well-rounded person,” she says.

She said, ‘I think this is what I’m going to do. It just seems like the right thing.’ So from that point on, everything was about learning about the Navy.

Donna York

on when her 8-year-old daughter, Caitlin Clark, decided that she would someday join the Navy

Two Purdue Global degrees helped me reinvent my path

Victoria Durnell’s online degrees have allowed her to rise in a new field and positively impact lives in her community

Victoria Durnell has used her Purdue Global bachelor’s and master’s degrees not only to change fields, but to create her own promotion. What’s next for her? Going back for her doctorate.

With every degree she has earned, she has moved forward in big ways. Her bachelor’s degree in health care administration allowed her a seamless transition from education to health care. After earning her master’s, she was not only hired, but created a new position for herself at Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. In the fall of 2024, she plans to go back again for her doctor of health science. She’s hoping to use her voice to write for publications on African American and women’s health issues — instigating change at the government level.

So what fostered this rise in a completely new career path?

A time for reinvention

Durnell had been working for years in an education administration role but felt her career was at a crossroads. With her superintendent retiring, she knew her school system would change and she didn’t want to get left behind. She was too young to retire, so she felt her options were to either stay in her current position or go back to school and change her field.

Durnell found herself looking in the mirror and reflecting on her career, asking, “Am I happy doing what I’m doing? Can I do this for another 15 or 20 years?”

These are difficult questions for any working adult to answer, but after considering her possible future paths, she knew what she had to do. After seeing an advertisement and enacting a quick Google search, she found the perfect avenue for what she calls her “reinvention”: earning her degree from Purdue Global.

I was able to take two years off my time earning my degree. It ended up saving me thousands of dollars.

Victoria Durnell

BS, MS health care administration ’21, ’23, Purdue Global

How does a person decide to pursue a completely new field after a long career in a different area? For Durnell, it was about discovering what she was truly passionate about. She realized it was her time to follow her love for sports and exercise, which also aligned perfectly with the growing health and wellness field. She noticed most medical offices need a health and wellness professional who focuses on keeping people healthy, and she wanted to be that person. Her previous experience in education involved administration and management, and she knew she could apply those skills to this new industry — an industry that excited her.

Another, very unexpected, person in Durnell’s life followed a similar career detour, which proved to her that she could make this dream a reality.

“My gynecologist was an English teacher, and when she retired, she went back to medical school and became a gynecologist. She is still an excellent surgeon at almost 80,” she says. “It just proved to me that it’s never too late.”

Purdue Global stepped in to foster that seamless transition from one field to the next. This change was made easier for her because she was able to translate her work and life experience into credits. “My advisor let me know that, because I was in a full-blown career, I was able to take two years off my time earning my degree. It ended up saving me thousands of dollars,” she says.

Durnell started toward her degree in 2019 and was able to earn her bachelor’s degree in 2021. She jumped quickly into her master’s program, once she realized it would move her even further along in a new career. “I knew the master’s degree was going to make me more marketable. When I looked into it, I noticed that the workload was very manageable and convenient,” she says.

Durnell celebrated her graduation with a master’s degree in health care administration by 2023.

“I just wanted to share it and shout it and let people know,” Durnell says, smiling as she reflects on her experience. “I thought to myself, ‘Wow, I really did do this.’ This was a four-year journey, and I was so proud of myself.”

Durnell is grateful that she could focus on school full-time and waited until finishing her master’s degree to apply for a new position. At first, she felt intimidated by rejoining the workforce but was pleasantly surprised by the outcome.

“I didn’t know what was going on in the world of employment,” she says, “so I threw my resume out there and I was very shocked at how many callbacks I got. The Purdue name helped.”

She landed a position as coordinator of health and wellness at Big Brothers Big Sisters, a title that attracted her because she knew she could use her school and administrative experience. Not long after starting work as a coordinator, she designed a new director role for herself from the ground up. She felt strongly that they needed someone who not only coordinates but assumes responsibility for the overall physical activities of the organization throughout the year. She ensures each activity resonates with grant requirements, organizational objectives, and most importantly, the children’s aspirations and needs.

“I kept advocating for that and it was created for me,” she says, overflowing with pride.

En route to a doctorate

Durnell loves her work now, and she only wants to increase the positive effect she has on others. When advocating for her new director position, she also told her CEO that she wanted to get her doctor of health science from Purdue Global.

When she talked to her husband about going back for her third degree, Durnell says, “My husband tells me he can’t even think of a time when I didn’t have a laptop in front of me. He actually just got his PhD, so he’s really proud.”

Soon there could be two Durnells with doctorates, an exciting thing for her to think about. “He pushes me to do things like pursuing my own doctorate degree. I’m so proud of him too, but of course my competitive side is jealous he got there first,” she says, chuckling.

When Durnell received a Purdue Global email with doctorate information, she looked at the course load and felt the pieces falling into place, exclaiming, “Oh, my God, this is for me!”

In her current role, she works with grant programs, which helped her realize a desire to dive further into public health issues and possibly work for the state. Indiana has been identified as a state with health challenges like obesity, smoking and food desert areas, and Durnell has made it her mission to bring exposure to these issues.

I’m changing lives with kids and families right now, and I enjoy this work so much.

Victoria Durnell BS, MS health care administration ’21, ’23, Purdue Global

“I’m changing lives with kids and families right now, and I enjoy this work so much, so I look forward to bringing more change,” Durnell says. She also has the long-term goal to write for publications on women’s health issues, a topic that was inspired by her family. Durnell has daughters, so she wants to help bring information to her own family, and women like them, so that they can learn more about their bodies and choices.

“It is a big deal for women to be able to know these things,” she says.

She is hoping to write about the intersectionality between African American studies, women’s health disparities and diabetes.

“I’m very passionate about that, so I’m definitely planning to dive in,” she says.

Deciding to return to school for the third time wasn’t an easy decision for Durnell, but she can’t wait to see what she will accomplish. After completely changing fields and creating her own position, there really is no limit to what change Durnell will inspire in her community once she holds a doctorate.

“The opportunity to tackle some of these issues is really big, and I think to have that credential will solidify that more for me,” she says. “The Purdue Global name on my doctorate will make it even better. I can see it.”

After taking a beat to think more about the future she is manifesting for herself by starting her doctor of health science in the fall of 2024, with an optimistic smirk, she concludes, “I’ll have a doctorate. Yeah, I’m that girl.”

‘Online safety is everything to me and my family’

This dad of four is driven to protect his people. So he’s earning his master’s degree in cybersecurity with Purdue Global.

Dan Vukobratovich (MS cybersecurity, Purdue Global) isn’t pursuing his master’s degree in cybersecurity simply because he likes tech.

It’s because protecting loved ones is something he takes very seriously. In fact, he would tell you his drive to protect his people is what informs every single thing he does.

He’s always been that way. When he first began to consider career paths as a young adult, he dreamed of a job in medicine. But as a dad of young kids at the time, he could tell right away it wasn’t going to work for his family. So he trained as a volunteer EMT and firefighter. In that role, he started to see how getting paid to work triage was not off the table.

“Once I got involved in emergency services, it drew my attention to cybersecurity because I realized it was actually a lot like medicine,” Vukobratovich says. “It’s the difference between dealing with the organic side of people and dealing with the nuts and bolts and wires. But the mindset is almost identical. You’re trying to figure out what’s wrong. You’re trying to help someone to safety.”

And when he decided to earn a master’s degree in cybersecurity management with Purdue Global, his understanding of the possibilities expanded beyond what he knew he could do. He could advance his career while holding steady in the day to day. He could teach a valuable lesson to his kids. And he could use his passion for safety to help other people learn how to protect themselves, too.

When you have a degree backed by Purdue, it’s a stamp of approval for a lot of people.

Dan Vukobratovich

MS cybersecurity, Purdue Global

Pursuing an online master’s degree in cybersecurity

His drive to protect his loved ones is ultimately what led him to cybersecurity, but being able to provide in the meantime is what made Purdue Global the right choice for him. The dad of four says flexibility was going to have to be central to his experience as a student — and that’s exactly what he got.

“Sessions are always after work hours,” he says. “It allows me to provide for my family, take care of the needs of my household. The faculty have been wonderful, but the students have, too. My study groups are really accommodating because we all need that.”

Vukobratovich works as a senior IT security analyst at Purdue Information Technology in West Lafayette, so the curriculum is directly relevant to his everyday life. As he helps the university evaluate the technology for security vulnerbilities, he’s regularly applying what he learns in class in addition to setting himself up for advancement later on.

“The class I just finished the term before this one was about network defense and penetration testing. With the upgrades to software at work, we have to actually evaluate everything from a criminal point of view — how can this be compromised, and what is our best defense against those compromises?” he says. “I’m able to take that exact, direct knowledge from class and apply it specifically to what I do.”

Value for his family

His family may be his primary motivation, but Vukobratovich is quick to note that their unwavering support also enables him to keep going — in particular, his wife, a full-time cardiac nurse.

“We’ve been married almost two years now and she’s my hero,” he says. “If she knows I have something big coming up or something I need to get done, she’s there saying, ‘Just go. Do it. I’ve got the kids.’”

And that’s what powers his capacity to model a valuable lesson for his kids in the meantime. His two daughters are now adults, but his sons — ages 10 and 11 — are at a famously challenging academic moment and being able to watch their dad push through it himself is meaningful.

“I want to expand how much I know, but I also want to set an example for my kids. Education is important. They don’t have a long-term vision right now, but I can show them it gets better,” he says.

He adds, with a laugh, that his wife’s excitement about what he’s doing is contagious.

“She’ll bend over backwards and then some to help make sure I can do this successfully,” he says. “She checked in with me about how it’s going. I said, ‘It’s going great.’ She said, ‘Cool. Do you think you want to get your doctorate next?’”

Her enthusiasm is precious to him, but he thinks he’ll get through the next year or so first before he starts considering the next degree. With everything put together, however, it’s grown his passion into something bigger.

“I want to spread the knowledge, teach people about it, show them how they can keep themselves safe,” he says.

An opportunity to keep his family safe and other families, too

Looking ahead, Vukobratovich is enjoying being able to think bigger.

“My focus is on critical infrastructure protection,” he explains. “Critical infrastructure is the underlying working fields that run our whole nation by running our local communities like the police department, the fire department, the military. But it also affects other things like finance, medical, transportation, logistics. Most people don’t realize how devastating an attack on these things can be. That’s why we’re seeing cyberattacks against electric companies, water companies, and I get to help keep those utilities safe.”

I want to spread the knowledge, teach people about (online safety), show them how they can keep themselves safe.

Dan Vukobratovich MS cybersecurity, Purdue Global

And in the age of AI, that unknown weighs heavy on a nervous public. Vukobratovich’s degree and skills allow him to stand in the gap.

“For a while, I taught some public classes on this material,” he says. “And I’d really like to do more of that when I graduate. I’d like to show people they can be safe online and that keeping their households and businesses safe may be easier than people think.”

In fact, he encourages those who are interested in educating others in cybersafety to consider Purdue Global. He says this is a field — even more so than most — where a respected name matters.

“People are worried right now. When they go to someone to learn how to keep themselves and their families safe, they want to know they can trust the person who’s teaching them. When you have a degree backed by Purdue, it’s a stamp of approval for a lot of people. They know the knowledge this educator is sharing is going to be accurate because they got their information from a renowned university,” he says.

In the meantime, what this degree is doing for him in the here and now is huge.

“Having the master’s degree can help me advance further within the university and support critical infrastructure,” he says. “But it also helps me work with leadership to better understand how IT and IT security can help the overall environment at Purdue.”

From here, he has nothing but inspiration and hope for the future. Vukobratovich has a vision that includes being published for his work in cybersecurity and infrastructure protection. He wants to present at a cybersecurity conference. But the possibilities are infinite.

“I’m proud of myself for discovering who I am, reinventing myself and continuing to pursue my education successfully,” he says. “A lot of men at some point need to evaluate — where am I, where’s my family at in life? — and find where that opportunity is. Your family is the one thing you really can’t replace.”

Virtual reality swim experience showcases Purdue talent in Indianapolis

Go behind the scenes of a VR game creation and learn more about Purdue’s new STEM-focused urban campus.

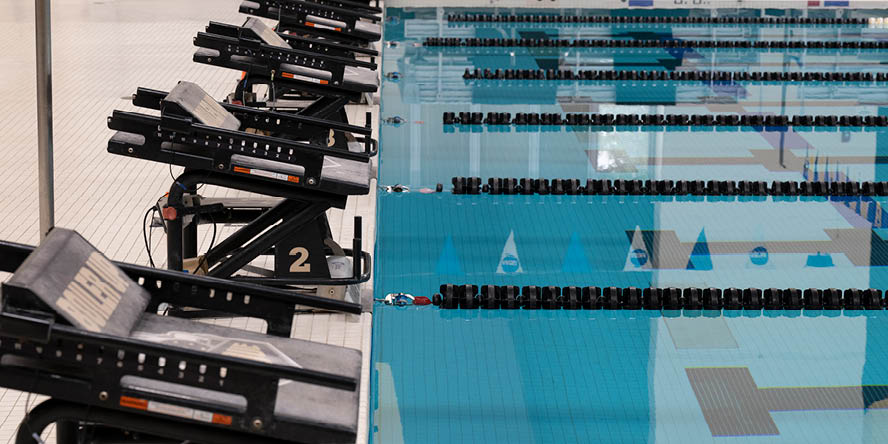

The horn sounds. You launch from the starting blocks, and the crowd goes wild. Purdue Pete cheers you on as you race down the pool. Flags are flying, and Boilermaker pride is all around you. Are your Olympic dreams coming true? Close. It’s the Purdue USA Swimming LIVE VR experience.

Purdue students and faculty in Indianapolis designed the VR experience to celebrate the U.S. Olympic Team Swimming Trials being held in Indiana’s capital city. Game participants are fully immersed in a 3D race in which they swim for a spot on an Olympics-inspired podium.

How the game is played (and made)

“The Purdue USA Swimming LIVE VR experience is interactive and fast,” says Jason Guy, clinical assistant professor of computer graphics technology. “Our goal is for any person of any age or ability to have fun. People can jump in and out of the game quickly.”

Creation of the multiplayer game was accelerated, too. It can take years to design a VR experience. But in just four weeks, Guy — along with students Andres Garcia de Quevedo, a junior animation major, and Lukas Wise, a senior computer graphics major — concepted, designed and built Purdue’s VR swim.

“The process of game creation is complex,” Wise says. “We break it down piece by piece and tackle each component individually. A lot of prep work goes in each step, so you need a solid plan before you start.”

User experience was a key consideration: Should the camera view be overhead and encompass the entire pool? Should it be a third-person view from behind the swimmer? What action should a player perform to advance their avatar? These are all questions that Guy, Wise and Garcia de Quevedo explored while designing the game.

“Andres did the menu setup,” Guy says. “This is what the players see when they first load into the game. And Lukas worked on the animations, getting the avatars to swim across the pool.”

Purdue Pete cheering you on? That’s all Guy. “I built Pete using Autodesk Maya, which is a 3D computer graphics application,” he explains. “Then I uploaded the screenshots into Unreal Engine 5, which is driving this game.”

Unreal Engine allowed Guy, Wise and Garcia de Quevedo to control lighting, perspective looping, the cheering animation of Purdue Pete, the Motion P on the bottom of the pool, the soundscape, as well as core functionality.

“Core functionality — pressing this does that — is always going to be the hardest aspect of game design in my opinion,” Wise says.

Purdue’s VR experience uses Meta Quest headsets, which go over a player’s eyes and ears. “They’re self-contained,” Guy says. “You don’t need a computer to run the game. It’s all in the headsets themselves.”

Wise and Garcia de Quevedo built the VR swim experience as part of a summer independent study they are doing with Guy. Hands-on learning experiences such as this are a big part of what drew them to Purdue in Indianapolis.

Industry experts, career-ready students in Indianapolis

“My professors are excellent,” Garcia de Quevedo says. “And they’re extremely supportive. I had a solid understanding of art and Adobe before I went into college, but my professors showed me how to use those skills to create something meaningful. They have pushed me to be the best I can be.”

Chris Rogers, site director and associate professor of computer graphics technology, says that having smaller class sizes allows him to forge these types of relationships with students. “I hold one-on-one sessions with students, even if it’s for just 15 minutes, to check in with them about class, but also to review their portfolios or hear about their career goals or internship interests.

“My area is video production and motion design. I love being able to help students along on their journey, and then, ultimately, hearing that they landed an amazing job and are really excited about what they’re doing.”

Creating connections between students and industry partners is equally important to Rogers.

“Conner Prairie is going through a major redesign of their entire experience right now,” he says. “The master planner for that project is one of our graduates, and we’re looking at new projects to do with them going forward.”

The process of game creation is complex. We break it down piece by piece and tackle each component individually. A lot of prep work goes into each step, so you need a solid plan before you start.

Lukas Wise Purdue computer graphics student in Indianapolis

He also points to recent associations with the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites and the Harrison Center, as well as a long-standing relationship with The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis.

“We are continually exploring opportunities that are unique to Indianapolis,” Rogers says. “Armando Lanuti, president of Creative Works, is on our advisory council. And we have cultivated a close relationship with the leadership of 16 Tech.”

Purdue’s Indianapolis location plays a key role in experiential learning, which is a point of emphasis for the urban campus.

“We’ve done many projects where we’ve partnered with outside entities,” Rogers says. “Being in the city, there are so many opportunities around tourism, sports and culture.”

“I am a huge fan of Indianapolis,” agrees Wise. “I love learning in an urban environment.”

Garcia de Quevedo says that the city helps him stay focused on outcomes. “I am career oriented and want to get my work done; Indy has been instrumental in that process.”

Collaborative, hands-on learning