Purdue x Vitality: Activewear for every body

Purdue partners with alumni-founded apparel company to bring branded Boilermaker athleticwear to all

Purdue University is embarking on a first-of-its-kind partnership with Boilermaker-owned athleticwear brand Vitality that emphasizes inclusivity, balance and community-building.

Owned by alumni sisters Taylor Chamberlain-Dilk and Chloe Chamberlain, Vitality’s brand mission closely aligns with Purdue’s spirit, and the partnership is looking to take giant leaps in collegiate collaborations.

“We’re proud to partner with Purdue University — the place that defined our college experience and provided us with the knowledge to pursue our dreams. This collaboration is a meaningful way for us to reconnect with a community we’ve always felt proud to be part of,” says the Vitality founders.

We’re proud to partner with Purdue University — the place that defined our college experience and provided us with the knowledge to pursue our dreams. This collaboration is a meaningful way for us to reconnect with a community we’ve always felt proud to be part of.

Vitality team

Launching April 12, Purdue x Vitality will feature a variety of Purdue-branded apparel geared toward both women and men. The clothing line features black-and-white sports bras, tank tops, leggings, shorts, T-shirts and long-sleeved shirts in the spirit of Purdue’s classic brand colors. These items will be sold online and in -person at the Purdue Team Store.

Vitality’s success

Sisters Chloe and Taylor didn’t necessarily plan to start a movement when they founded Vitality in 2018 with Taylor’s husband, Steve Dilk.

At the time, the three Purdue graduates weren’t even sure what they wanted their new family business to sell.

“We didn’t know what it would be at first, but we knew we wanted to start one as sisters and as a family,” says Chamberlain (BS organizational leadership ’20), the company’s chief of design.

Initially, they might not have imagined that their new business would develop a cult following on social media or that they would someday show off collections at New York Fashion Week, but that’s exactly what happened. And their rapid success is not simply the product of being in the right place at the right time during the athleisure boom of the past few years.

The company strategically found a niche with its embrace of inclusivity and sustainability, creating stylish and comfortable apparel that flatters all body types — with sizes from XXS to 4XL. Their commitment to fostering community within their customer base has clearly paid off, as Vitality’’s loyal fans eagerly grab new collections the moment they launch online.

The company’s website explains, “We’re a society of mutual support, where doers, the daring, and dreamers can draw from — and give back to — the energy of a purposeful collective.” Industry analysts and insiders have taken note of the company’s success.

Forbes Magazine selected Chloe, Taylor and Steve for its prestigious 2022 30 Under 30 list honoring top young professionals in the North American retail and e-commerce market. In the blurb honoring the three Boilermakers, Forbes marveled at how their company’s sales skyrocketed from zero to $36 million within three years.

In 2021, fashion platform Runway 7 invited Vitality to participate in its New York Fashion Week showcase for independent designers and renowned brands. Chloe created the company’s Panorama collection to debut at the prestigious event at New York’s Sony Hall.

The family business that started in their Denver garage with their personal savings has quickly become an incredibly successful story of DIY entrepreneurship. It’s a story rooted in their experiences at Purdue. “Purdue helped us become balanced people,” Chloe says. “We became communicators, leaders and entrepreneurs with the help of our educations. We want to continue to impact others’ lives and the community we’ve created. We always are working to be better versions of ourselves and to find our own balance in work, business and life. We hope others can find the same.”

Purdue helped us become balanced people. We became communicators, leaders and entrepreneurs with the help of our educations. We want to continue to impact others’ lives and the community we’ve created.

Chloe ChamBerlain (BS Organizational Leadership ’20) Chief Of Design

From Boilermaker beginnings

The sisters grew up in a household that valued fitness. Their mom was a Denver Broncos cheerleader. Their dad was a bodybuilder.

Wanting to follow in their footsteps, Taylor (BS nutrition and dietetics ’15) eventually chose a health-related major.

“Fitness was ingrained into our lifestyle ever since I can remember,” says Taylor, Vitality’s chief executive officer. “Seeing my parents compete in bodybuilding sparked my own passion to pursue that. I enjoyed learning about nutrition and thought, ‘Why not become a dietitian?’”

While in college, she launched a social media channel to inspire others through her own fitness journey, sharing recipes and training clients. She ultimately earned a personal training license, becoming a trainer at Purdue’s France A. Córdova Recreational Sports Center. In time, Taylor and her sister attempted the giant leap of building a health-related style business, by women, for women.

“After we both graduated, I started to become a fitness influencer on Instagram, and knew I had a passion to create some sort of business that could make an impact on countless people,” Taylor says. “Chloe and I saw a gap in the athletics industry for high-quality, reasonably priced athleticwear that would fit all shapes, sizes and backgrounds.”

They evaluated other athleticwear companies and knew they could make the industry more inclusive, so they decided to introduce a workout brand that appealed to all body types.

“We came up with the mission to unite men and women of all shapes, sizes and backgrounds to form a culture of inclusivity and help people find their own balance in life — whatever that may be for them,” Chloe says. That mission is embedded in their brand.

“Evolution is taking intentional steps toward being better every single day,” Steve (BS biochemistry ’15) explains. “Whether it’s a large step or a small step, what matters most is you are moving forward. We know that if we are taking steps every day, collectively as a team, and as long as we are holding each other accountable to take those steps, we are going to evolve. Vitality embodies this evolution and elevation as a brand, and we are in a magnificent position to take everything to the next level.”

Judging by the massive following the family has built for their brand, their message has connected with its intended audience and with the Purdue brand of persistence and innovation, where the sky is the limit from here.

A Boilermaker fan cave dedicated to the Purdue Grand Prix

In his Purdue-themed workout room, Travis Iles displays numerous race mementos, including his 2009 winner’s trophy

The typical Purdue fan cave likely features a few staple items. Old sports memorabilia. Campus photographs that hold personal meaning for the owner. Lots of old gold and black.

The Boilermaker-themed workout room in Travis Iles’ home in Columbus, Ohio, has all those things, but with a twist. Most of the adornments relate to a specific campus event that greatly impacted his Purdue experience and postcollege life: his four years spent driving a Sigma Chi go-kart in the Purdue Grand Prix.

Iles (BS industrial management ’10) is tremendously proud of the oversized winner’s trophy displayed in the corner of the room, a prize he received in 2009 after leading for the final 120 laps of the 160-lap race. But he also looks at the display box full of race mementos and celebratory photos with his parents and fraternity teammates and thinks back on the life lessons and long-standing friendships he gained through those years competing in “The Greatest Spectacle in College Racing.”

“I was involved in a lot on campus, but I would say the Purdue Grand Prix was definitely something really special to me,” Iles says. “If I think about the guys that I’m still friends with today, it’s almost like a subset of the fraternity. We’re all Grand Prix guys who spent so much time dedicated to a common goal.

“We learned a lot and raised the money and busted our knuckles. We just had a bunch of guys that were real passionate about it, and that’s why we’re still close today. My crew chief (Sheldon Alt) was the best man in my wedding, and I was his.”

Iles and his Sigma Chi teammates completed a successful four-year run at the Grand Prix, improving from an 11th-place finish while operating on a shoestring budget during his freshman year to becoming true championship contenders in each of the next three. He was leading the race as a sophomore before blowing an engine. (“Six-dollar part,” Iles recalls with a laugh. “That’s how it always is.”) He stalled on the grid as a junior before racing his way back to fifth place. And then fortune finally turned in his team’s favor in the 52nd running of the race.

“We were really fast all those years. My senior year, everything just kind of went right,” he says. “We took the lead on lap 40 or something and just never looked back.”

By winning the race, Iles earned an opportunity to serve as an honorary starter for an Indianapolis 500 practice session on May 15, 2009 — and he got to invite his dad and some friends to join him at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway that day.

That was one of many post-Grand Prix bonding experiences for the group of friends, who frequently returned to campus in the years after graduation for an informal homecoming on Grand Prix weekend. Because the race was such a cherished memory, they also worked to pay it forward to the next generation of Sigma Chi racers.

Their race team had to rent shop space during Iles’ junior and senior years while their fraternity house was being renovated, which created numerous logistical challenges. So he and his crew chief, Alt, decided to spearhead a campaign to build a permanent facility for the Sigma Chi team and help with other fundraising efforts even today.

“That actually is even more of an important legacy for me, that our names are on the outside of the garage. I’ve got a 4-year-old and a 2-year-old, and when we go back, we can show them, ‘This is Daddy’s go-kart shop,’” Iles says.

While most of the memorabilia in Iles’ Purdue-themed room centers around his Grand Prix experience, it’s not entirely race-related. For example, there is a plastic photo cutout of his daughter Georgia that was displayed alongside thousands of other Boilermaker fans’ photos in the bleachers at Ross-Ade Stadium during the pandemic-impacted 2020 football season. There is also a plywood Motion P logo that his dad made as a decoration for the 2013 wedding between Travis and his wife, Tracey (BA public relations and advertising ’10), whom he began dating at Purdue.

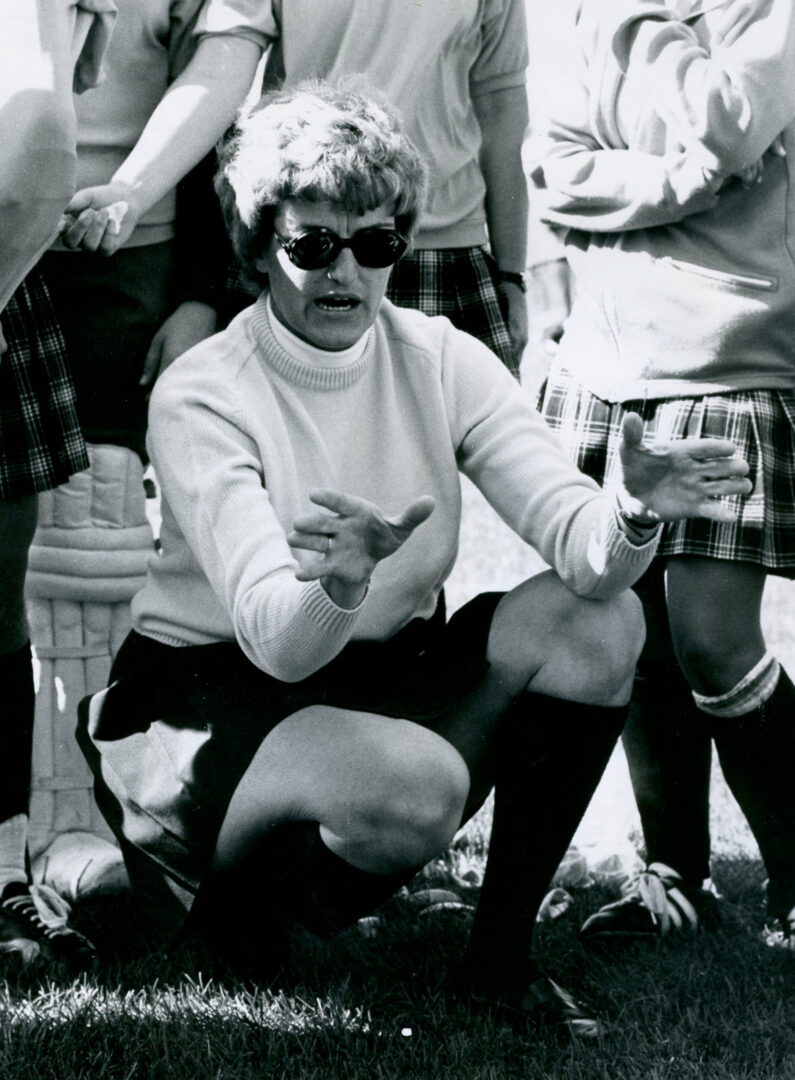

Boilermaker ties run deep on both sides of Travis and Tracey’s family, as Travis’ mom and Tracey’s parents, sister and grandfather are also Purdue alumni. In fact, Tracey’s mom, Lisa (Ross) Todd, was once the Girl in Black featured twirler in the Purdue “All-American” Marching Band and serves as a band board member today. These connections only deepen their affection for their alma mater.

“Both my wife and I and our entire family have strong and warm emotions about the time there,” he says. “When so much life happens on a piece of ground, I think that you have this immediate kind of connection to that place.”

And then there are the practical lessons he gained at Purdue that helped him build a career as a district sales manager at Abbott. Iles acknowledges that he certainly benefited from the world-class education available at Purdue, but he also recognizes how his time in West Lafayette helped him build essential skills for a career in medical sales.

He learned how to engage with people from many different walks of life as a Boilermaker student. And all those hours spent scraping together the roughly $10,000 his Sigma Chi team needed each year to keep their kart running? It turns out they helped him land his first job.

“I’ll never forget my interview for Abbott, which was in the Purdue Memorial Union. The interviewer’s question was something like, ‘What makes you think you can go and sell?’ and I was like, ‘Once you’ve been selling fraternity go-kart racing to small businesses in Lafayette, you can sell anything.’ And he kind of got a kick out of that,” Iles says. “But that’s the truth. Being persistent and being somebody that people are willing to meet with, that’s a big part of it. And that’s what we were doing when we were 20 and 22.”

Both my wife and I and our entire family have strong and warm emotions about the time there. When so much life happens on a piece of ground, I think that you have this immediate kind of connection to that place.

Travis Iles

BS industrial management ’10

An insider’s perspective on the new and improved IMS Museum

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum’s tour operations manager, a Purdue alum, shares what to expect after renovations

Visitors to the new and improved Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum will receive a musical welcome from an ensemble that Boilermakers know well.

Just as the Purdue “All-American” Marching Band helps kick off the Indianapolis 500 each year by performing “Back Home Again in Indiana” moments before the race starts, the band will now help museum guests begin their visits in an immersive video sequence that places them at start of “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing.”

“The Purdue band features largely in that new video,” says Brian Bobay (BA social studies education ’07), the IMS Museum’s tour operations manager. “There are planes flying overhead. It has three IndyCars, patterned after the front row of that year at the start of the 500 — so every year, there are actually going to be different liveries on those cars as the front row is displayed. It has a gigantic screen overhead with various things and activities that start on race day. It’s basically like you’re experiencing the start of the Indy 500.”

And that’s just one of the many exciting changes that visitors will encounter when the museum reopens April 2. The museum closed for renovations in November 2023 as part of an $89 million campaign that significantly expanded its exhibition space and allowed for much-needed technological upgrades that create an exciting, interactive guest experience.

Now the museum is ready to once again greet visitors from all over the world, and Bobay is here to share what guests can expect from the revamped facility. In this abridged Q&A, the Purdue alum discusses must-see museum additions and how he has a perfect job for a history buff and racing enthusiast:

Q: Is it accurate to say the primary reason for the renovation was to bring the museum up to date?

A: Very accurate. Don’t get me wrong, I loved the museum as it was. As a kid, I can remember going in and seeing all the cars there. But part of the problem was what I remember as a kid is exactly how it was in 2023 when we closed. Lots of cool cars, but not a lot of interactive stuff. And for little kids, there was only so much you could do.

Whereas now in the new, updated museum, there’s a boatload of stuff for anybody of any age to do. A lot more interactive stuff. There’s a specific area for little children to do hands-on stuff like slot-car racing. There’s an interactive pit stop challenge. We’ve got racing simulators. A program with an interactive, almost simulation-based thing, where scenarios play out before you. You’re essentially the crew chief: You select a scenario, and it tells you whether your car decreased position or increased position, and then you move to the next scenario.

And we still have a bunch of cars displayed in an awesome way. Everything was kind of flat in the old museum, but some of the cars now are on a 9-degree banking, like the track. Others are at about a 45-degree banking, displayed so you can see more of the cars in different perspectives.

Q: Are there other ways the museum will be different now?

A: A whole bunch of ways. (IMS owner) Roger Penske has a special area in the back of the museum dedicated to his racing team and his successes at Indy, which have been numerous.

There’s now a mezzanine. It used to be just one floor: the cars on display, and that was it. The ceiling was so high, so they built in a mezzanine that you can walk up and see the cars below you. Below the mezzanine is where the Borg-Warner (Indy 500 winner’s trophy) is displayed. Also, the basement is being utilized in the museum’s primary display area, where it used to be this gigantic off-limits thing where all the cars were packed.

We’ll have about the same number of cars on display as before, just a little bit more spread out, and different angles, different perspectives that you didn’t get to see before. There are going to be, typically, two temporary exhibits. One right now celebrates the NASCAR Brickyard 400 with eight winning cars from that race. And then another temporary display is based on the four four-time winners of the Indianapolis 500.

A lot of the other things are dedicated to the winning cars of the 500, and those are going to be more permanent on display. As far as artifacts, you’ll see a whole bunch more than you did before. A lot of that is located on the mezzanine level.

Also, there’s a section dedicated to just about every major race that has been here. There’s a section dedicated to Formula One, some to sports cars, the Red Bull Air Race that was here for a couple years, to the USAC BC39 race that we have on the small dirt track out there. Before, the museum was geared almost 100% to the Indianapolis 500, but now we have space and the means to celebrate everything that was taking place here, not just the 500.

We get visitors, literally, from around the world. I’ve probably met someone from just about every single country in my 10 years here.

Brian Bobay (BA social studies education ’07)

Tour operations manager, Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum

Q: If a museum guest were to ask you where they should go first now, where would you send them?

A: In the old museum, people came in and said, “Where should I go first?” And it was like, “Well, your choice.” You’d walk in and you had all the cars in front of you — winning cars over to the right, special exhibit off to the left, and so on and so forth.

Now it’s more of a guided path. You come in and the very first thing you see — and this is a neat thing right off the bat — is it shows the evolution of Gasoline Alley and the garage area. There are seven different garages with cars in them, and each one is period-patterned so you can see how the garages evolved as you’re walking through this exhibit. And as you look down, because the track surface went from something called taroid to brick to asphalt, the floor below you changes from era to era.

That’s what you’re immediately greeted with. Then you walk around the corner, and that’s where the Purdue band is featured in the video that simulates the start of the 500.

Q: What are some of your favorite items to show guests at the museum?

A: The Borg-Warner is always one of the more popular ones for people. And the Marmon Wasp, the winning car in 1911.

My favorite thing is to show the evolution of the cars. It isn’t one specific thing — it’s that all together you can see what came after this 1911 Indy car. It’s amazing to tell people that it didn’t have seat belts or anything, and it’s still going highway speeds at that time period. So just think of the bravery of those drivers.

I also like to tell people that the first rearview mirror is said to be on that 1911 car. The story behind that was, back in those days, cars always had a driver and a riding mechanic. Ray Harroun was the pilot of the Wasp in 1911, but it was a solo-seat car, so people complained that he didn’t have a co-pilot on board to look around and alert the driver if there’s a car around. To counteract that, Harroun installed what is thought to be the first rearview mirror up in the Marmon Wasp.

Now, if you remember, the track in 1911 was completely brick. If you’ve ever been on a car riding on bricks, the rearview mirror was probably pointless because the ride was so bumpy. But it was there, so that gave the other drivers some comfort.

Q: What would you say is the primary role of the IMS Museum?

A: We’re the custodians of the history of the place. Why is it important? Well, it’s a vital part of Indiana history. We get visitors, literally, from around the world. I’ve probably met someone from just about every single country in my 10 years here. They fly into Indianapolis, and even if they know nothing about our city, the one thing they know of is the Indianapolis 500, so they make their way here.

Also, we’re the point of contact for people for most of the year. There are four or five major racing events at IMS, but every other day of the year when people come to the track, it’s us that they’re dealing with. So even though we aren’t exactly associated with the Speedway per se, we’re the face of it at times. So it’s our job to make a good impression and to emphasize why this place is important.

Q: What does being the museum’s tour operations manager entail?

A: Essentially, I make sure the trains run on time. I’m in charge of basically about 40 to 50 tour guides and drivers. So I make sure we have the proper schedules for guides. If need be, I create tour routes and work closely with IMS.

A lot of people in Indiana don’t realize that the museum is actually separate from the Speedway. When people think of the museum, they think basically Roger Penske is running the museum. That’s not quite accurate. So a large part of my job is working directly with my IMS counterpart and seeing when we can have track access. If we can’t, what can we do beyond that? And then kind of taking that information and planning out the day from there.

Q: How long have you been interested in racing?

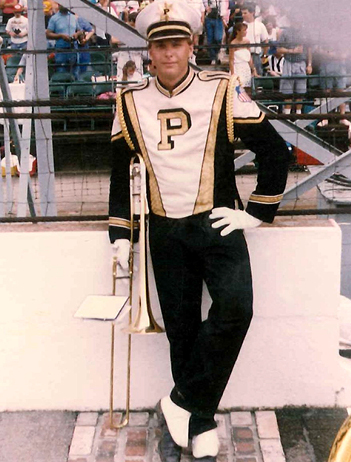

A: Basically from birth. Obviously, being from (Fort Wayne) Indiana, the Indy 500 is on every single May. My dad started taking me to time trials when I was really young. My brother (Chris, BS civil engineering ’92), played trombone in the Purdue band from 1988 to ’92, so he was always there, because the Purdue band is always there. We were always looking on TV, saying, “Hey, where’s Chris?” And he always used to bring me back a little toy car, too. So all those factors played into my love of it.

And then as I got older, I got into history, which is why I went to Purdue. The history of the entire facility is fascinating, dating back to 1909 — and some of the characters behind IMS, the history dates back even way before that.

Q: Leading IMS tours seems like a perfect job for someone who’s interested in racing and history.

A: Oh yeah. People ask if I’m working my dream job, and I say, “Yeah. It’s still a job at times — all jobs are — but yeah, I’m definitely pretty lucky.” I originally thought I was going to be a high school teacher for the rest of my life. I did that for three years and decided it wasn’t exactly for me before I eventually came here. And now a decade later, here I am.

Redefining the Boilermaker experience

Purdue’s Academic Success Building in Indianapolis will enhance hands-on learning and innovation

For students like Aurelia Chelfannisa, the benefits of Purdue University’s new Academic Success Building (ASB) in Indianapolis will make a meaningful impact in more ways than one.

The first-year biomedical engineering student is already taking advantage of a research opportunity with her professor. And she is excited that the new space will create more student research opportunities — plus offer a home away from home where she and her classmates can not only work and learn, but live and support one another.

Originally from Singapore, she chose Purdue for the world-class engineering education she could receive in Indianapolis while attending college in a big city that reminded her of home.

She is eager to have a space to strengthen the close-knit campus community.

“This building will be a Purdue campus center to hang out and meet up for group projects,” she says. “Campus living also helped me feel welcome. This new addition will help a lot of students adjust to campus life.”

When it opens in May 2027, the ASB will further expand Purdue’s footprint in Indianapolis. It will be an innovative, all-encompassing central hub for students. The building will include areas for housing and dining, seven large classrooms, a makerspace, two chemistry laboratories, conference rooms, community venues, and retail spaces.

“This is the first major new building in Indianapolis that will serve the long-term need for a real Purdue hub,” says David Umulis, Purdue’s senior vice provost Indianapolis. “A place for students to call home, participate, advance training, socialize and partner with the community.”

Increasing access to partners

The ASB embodies Purdue’s investment in its current and future students.

Nestled in the heart of the city, the facility will be surrounded by a historic neighborhood and near corporate and nonprofit partners like Elanco, Elevance Health, Eli Lilly and Company and The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis.

Zachary Lear, a sophomore double-majoring in mechanical and motorsports engineering, says that this proximity will continue to prepare him for a career in the automotive design world.

Lear, who dreams of becoming an automotive engineer for a race team, already benefits from industry access in his classes and through exposure to the motorsports club in Indianapolis. He is thrilled about the flexible, tech-forward spaces the ASB will provide.

“I feel that everyone can benefit,” Lear says. “Tech is evolving, and we need hands-on experience in working with 3D printers and the fabrication and design that’s important for engineering.”

Enhancing hands-on training

Experiential education at Purdue focuses on seven main pillars, including work-integrated learning, research and scholarly projects, and engaged campus experiences. These pillars extend to university programs like EPICS, a service-learning design program, and The Data Mine.

Kate Caward, assistant director of the Office of Experiential Education in Indianapolis, says that the ASB will directly support these core offerings, creating more opportunities for undergraduate research, partner collaboration, industry mentorship and events like career fairs and industry interviews.

“The ASB will provide space for us to grow and offer better services to our students,” Caward says.

Those efforts will open doors for students like Ishita Mukadam, a freshman in biomedical engineering who founded the Purdue in Indianapolis Medical Association to increase student networking with the medical and health care industry.

Mukadam is driven to pursue and highlight health care on campus, and she’s confident that the resources available in the ASB will help students like her reach their goals.

“I think a lot of people on campus feel a sense of community because we all chose Indy for a reason, which in a way unites us,” says Mukadam, who has already landed an internship at Neurava, a medical device startup focusing on epilepsy research. “Having a building of our own is going to be really valuable.”

And this is only the beginning. Designed to provide both formal and informal educational opportunities in a centralized location in downtown Indianapolis, the ASB represents a giant leap toward realizing Purdue’s vision for its expansion into Indiana’s capital city.

“Though this is Purdue University’s first major development in Indianapolis, it certainly won’t be our last,” says Evan Hawkins, Purdue’s senior director for administrative operations in Indianapolis. “We look forward to the positive impact our facility will bring.”

This is the first major new building in Indianapolis that will serve the long-term need for a real Purdue hub. A place for students to call home, participate, advance training, socialize and partner with the community.

David M. Umulis, Senior vice provost

Purdue University for Indianapolis

A unique opportunity to thank a fellow Boilermaker

At a Glance:

- See how a tech breakthrough (with a Purdue tie) empowers student Morgan Malaski to navigate college with diabetes.

- Discover how a Purdue alum, now Dexcom’s R&D chief, helps shape the technology Morgan relies on every day.

- From using Dexcom’s life-changing tech to interning at Eli Lilly and Company, follow Morgan’s journey as she turns personal challenges into professional ambition.

Student with Type 1 diabetes relishes meeting Purdue alum who leads R&D at the company whose CGM system changed her life

What would you say to someone whose work makes your life better?

And what would it mean if that person attended the same university you do, knowing that their efforts allow you to live independently?

When Purdue student Morgan Malaski met Girish Naganathan (MSME ’99), chief technology officer at California-based Dexcom Inc., she was thrilled to have an opportunity to answer those questions.

“I’m really grateful for that experience,” she says.

Morgan — diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at age 6 — doubts she would have been able to leave her home in Portage, Indiana, for college if not for Dexcom’s continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system that she wears each day.

Without a normally functioning pancreas producing insulin at sufficient levels to reduce the amount of sugar in their bloodstream, people like Morgan with Type 1 diabetes are at risk of developing life-threatening health complications. But thanks to the real-time feedback that Dexcom’s CGM technology provides, Morgan has been able to manage the chronic illness and thrive in her freshman year at Purdue.

That’s one of the primary reasons that Morgan’s parents, Mindy (BA education ’99) and Matt, were also excited to meet Naganathan. Armed with the real-time feedback the device transmits, Mindy and Matt’s lives also changed for the better once Morgan became a Dexcom user at age 8.

“Dexcom saves us,” says Mindy, who used to get up every two hours each night to check on Morgan before the FDA approved Dexcom for children’s use. “I could cry. The two years that we lived without Dexcom with her, it was frightening as a mom. I’m sure my cortisol levels were through the roof, just awake all the time, worried about my kid, worried that she wouldn’t wake up. But with the Dexcom, I can sleep and get through the night. It’s amazing technology, and it keeps getting better. We just love them so much.”

Naganathan, who spearheads Dexcom’s research and development efforts, spent most of his career in the consumer electronics sector, so he was unaccustomed to hearing such passionate customer testimonials before accepting his current position. That changed almost immediately after joining Dexcom, when thank-you notes began rolling in from families like the Malaskis.

“I had so many friends or colleagues write to me on LinkedIn talking about how it changed their life or how they don’t have to worry because of Dexcom,” Naganathan says. “All the stress of what goes on behind the scenes to make all this happen just fades away when you’re thinking about how the end result of what you’re working on has got this profound impact.

“It was truly humbling. I realized I’m on a path doing work that really matters at Dexcom.”

Indeed he is, and Morgan’s story is just one example of the good that can come from exceptional Boilermakers like Naganathan tackling the world’s toughest challenges. Diabetes increasingly fits that description, as approximately 30 million Americans have been diagnosed (Type 1 and Type 2 combined) with this condition that puts them at higher risk of heart disease, stroke and many other complications that can result in premature death.

A normal life at Purdue

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Dexcom’s CGM technology is that it enables users to do the everyday, average stuff that would have been much more difficult without it. With the sensor attached to her upper arm, Morgan can more easily live 90 minutes away from home and enjoy the lifestyle of a typical college student.

She’s studying biology and supports the College of Science as a student ambassador. She and her roommate signed up to play intramural soccer. And she joined the Higher Ground Dance Company, which allows her to participate in a favorite activity since childhood.

She’s able to do all of that with a relatively low degree of stress because she knows her Dexcom CGM system will check her glucose levels every five minutes and alert her if it’s too low or too high.

“The biggest advantage, and what allows that freedom, is just having that information,” Matt says. “Whether you’re actively looking at it or not, if it’s not where it’s supposed to be, it’s going to beep. Then you know you’re not in the right place. And so just having that information prior to going into a dance session where you know you’re going to be dancing for 45 minutes, an hour straight — ‘If I’m getting low, I should have something to eat before I start this.’ Knowledge is power.”

“And it’s just nice to have backup in that situation,” Morgan adds.

This fall, she’ll take part in her guaranteed internship with Eli Lilly and Company through the Lilly Scholars at Purdue program in another twist in her story as a Boilermaker with diabetes. The internship at the Indianapolis-based company will give her an opportunity to evaluate a longtime career goal of working in R&D in the pharmaceutical industry. And it will allow her to do so at the company that was the first commercial manufacturer of insulin.

“That’s like a God wink,” Mindy says of the meaningful connection between the internship program and her family’s journey with the chronic illness Lilly is best known for combating.

“It will be a full-circle moment,” Morgan agrees. “Since I was little, I knew I wanted to give back to the people who have developed and researched and manufactured things that either make my day-to-day easier or literally keep me alive.”

There is another notable way that work being done at Purdue might someday make Morgan’s daily routine easier, and it might not seem especially obvious.

A Dexcom monitor relies on two primary semiconductor devices to operate effectively: the analog front end that deciphers minuscule changes in a person’s blood glucose levels, plus the Bluetooth chipset that transmits the readings to a mobile device. The groundbreaking semiconductor research being done at Purdue could someday help Dexcom engineers create devices that are smaller, more accurate, more comfortable to wear, more feature-packed or that benefit from any number of additional innovations.

“Semiconductors are critical,” Naganathan says. “Without semiconductors, the system cannot work.”

Since I was little, I knew I wanted to give back to the people who have developed and researched and manufactured things that either make my day-to-day easier or literally keep me alive.

Morgan Malaski

Purdue freshman and Dexcom user

‘You get used to beeps very quickly’

Although the Malaskis previously had no family history of diabetes, Morgan is actually not the only person in their household to be diagnosed with the disease. Her 14-year-old brother, Myron, was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at age 10 and also uses a Dexcom CGM today.

Their parents by now are accustomed to smartphone notifications, either from Morgan’s insulin pump or from the Dexcom Share feature that allows them to view the activity on each child’s glucose monitoring devices.

“Around our house, you get very used to beeps very quickly,” Mindy says. “It gives us a little insight into what’s happening in that situation so that even now with Morgan being down at Purdue, if we get an alert on our phone, then we can see it and hear it. Because when she beeps, we beep.”

Morgan began using the insulin pump during high school, thereby introducing another layer of precision to her daily fight against diabetes. The pump syncs with her Dexcom system and can respond autonomously, administering the exact insulin dosage necessary according to the monitor’s readings.

“That’s another part of Dexcom that was a great next step for us,” Matt says. “We had the knowledge. Now we have something that could be done with it more actively, more precisely than we could do with the normal method of delivery, which was an insulin pen and needles. You have a certain amount of inherent being off when you’re doing it that way because you have to either give (insulin) in a full unit or in a half unit, whereas this gives such small doses that it can do zero-point-whatever that the algorithm determines is necessary to get within the range it’s supposed to be.”

That range is a constantly moving target, however.

Morgan is able to occasionally indulge in a sugary dessert or a carb-heavy meal like pizza, but she does so with the knowledge that diabetes never takes a break. While she can take proactive steps to counteract the effects of whatever she consumes, the need for vigilance is ever present.

That constant battle is why Dexcom frequently refers to its customers as “Dexcom Warriors.”

“Dexcom is the ammunition for them to truly fight against it,” Naganathan says. “It informs them. It gives them protection. It gives them alerts. It wakes them up. It indicates to them when they’re going to go high or low. And they can go about living their lives without thinking about the disease because there’s a device that’s working on their behalf, thinking about the disease, that’s the most accurate device in the world.”

We want to support all of our patients. But when you bring it close to home to say it’s enabling somebody to go to the same school that you attended, it removes one more degree of separation and brings that closeness.

Girish Naganathan (MSME ’99)

Chief technology officer, Dexcom, Inc.

Tough conversations, important tests

Sending children away for college is a high-stress time for any parent, and that was especially the case for the Malaskis.

They credit participation in a study at Chicago’s Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital — where their kids were treated for diabetes — for giving them the tools necessary to help Morgan and Myron become more independent. The Malaskis say the Transition Readiness: A Family-Centered Experience (TRACE) study provided space to have tough conversations with their children about being away from home and managing their own medical care.

“The study provided us more meaningful avenues to have those conversations where it wasn’t adversarial,” Matt says. “It was just ‘Here are our thoughts. What are your thoughts? Where can we come to a consensus of what these next years are going to look like?’”

One result of those conversations is that Matt and Mindy agreed to wait 15 minutes after receiving a Dexcom notification before reaching out to make sure Morgan addressed the situation. After the 15-minute mark, they are free to repeatedly contact her until they know she has taken corrective steps.

“It gives them peace of mind that they can see it too,” Morgan says. “If they need to call me, they call me.”

Sleepaway dance camps at Ball State University each summer also helped settle the Malaskis’ nerves, providing short-term opportunities for Morgan to prove she was ready for the responsibilities of college.

“That was entrusting Morgan with ‘You want to go away for school, here’s your chance. You know what you need to do. You need to text us. You need to keep us in the loop.’ And she was very good about it. So we did feel confident when she was ready to go away to Purdue,” Mindy says.

Morgan has always been a responsible kid, so her parents weren’t surprised that she passed another independence test with similar success at Purdue, largely thanks to the Dexcom technology.

And when she and her family had a chance to meet Naganathan and thank him for the system that changed their lives, they seized the opportunity.

“It’s really cool to meet one of the people who helps make my life so much easier,” Morgan says.

Naganathan always enjoys the warm-and-fuzzy feelings that come from hearing about a Dexcom user’s positive experiences. However, he acknowledges that these testimonials seem extra meaningful when they have personal connections — like with a certain Boilermaker who thanks to Dexcom is better prepared to fulfill her potential and live a happier, healthier life.

“We want to support all of our patients,” Naganathan says. “But when you bring it close to home to say it’s enabling somebody to go to the same school that you attended, it removes one more degree of separation and brings that closeness.”

5 legendary Purdue women every Boilermaker should know

Purdue historian discusses legacies of Amelia Earhart, Lillian Gilbreth, Mary Matthews, Helen Schleman and Dorothy Stratton

Most Purdue people know Amelia Earhart was a Boilermaker.

But what about the other trailblazing women whose influence changed Purdue for the better? Do alums know about the former dean of women for whom Schleman Hall is named? Do students know why the Veteran and Military Success Center is named for Dorothy Stratton or that Matthews Hall is dedicated to the first female academic dean on campus?

These are the stories that historian and author Angie Klink (BA communication ’81) especially loves to tell.

“Amelia Earhart gets a lot of press, and we love her, but there are so many other stories to tell that go untold because people don’t even know they exist,” Klink says. “I’m always trying to get the story out there that’s fresh and new and that no one knows about. That’s important.”

As is the case with several of her other works, Klink’s new book — “Purdue’s Female Founders: The Untold History of Trailblazing Women Faculty,” which Purdue University Press will publish in fall 2025 — shares the stories of Purdue women and their persistent pursuit of their ambitions. It covers multiple generations of important historical figures, from artist and professor Laura Anne Fry in the late 19th century to Christine Ladisch, who became the inaugural dean of the College of Health and Human Sciences in 2010.

Many Boilermakers don’t know these women’s stories, but they should, Klink says.

“That’s why it’s important to write these stories down, because other generations have no idea whose shoulders they’re standing on,” Klink says.

As Purdue women icons, no shoulders are any broader than those of Earhart, Stratton, Lillian Gilbreth, Mary Matthews and Helen Schleman. For those who want to learn about their monumental impact on the university’s evolution, Klink is happy to share why these are five women every Boilermaker should know.

AMELIA EARHART

The iconic aviator’s time at Purdue was relatively brief — from 1935-37 — but her influence is evident across campus even today.

There’s Amelia Earhart Residence Hall, which features a statue of the pilot outside the front doors. There’s the Amelia Earhart Faculty-in-Residence Program that allows participating faculty to mentor students while living in a Purdue residence hall, as Earhart did nearly a century ago. There’s the Amelia Earhart Scholarship for students who exhibit special leadership and determination. And who else could Purdue have named the new terminal building after when it brought back commercial air service to the Purdue University Airport?

After all, Klink says, it was the airport that helped convince Earhart to accept a position at Purdue.

“Purdue was the only college in the country that had its own airport, and that was what drew her here,” Klink says. “Plus, she wanted to influence careers for women. She really saw it as an opportunity to help women students.”

For a few weeks each semester, Earhart lived on campus in Duhme Hall and worked as a career counselor for women students and advisor to the aeronautical engineering department. “Career counselor for women” was not exactly a job that existed anywhere else in 1935, but Earhart had already proven what women could accomplish when they pursued their dreams — and her ideas resonated with the women she befriended at Purdue like Stratton and Schleman.

“The women students were in awe of her,” Klink says. “Who wouldn’t be? She was an international celebrity.”

(Amelia Earhart) wanted to influence careers for women. She really saw it as an opportunity to help women students.

Angie Klink (BA communication ’81)

Purdue historian and author

Purdue’s airport was home base for Earhart’s preparations for the around-the-world flight attempt in 1937 where she went missing. The Purdue Research Foundation even financed Earhart’s purchase of a Lockheed Electra 10E airplane — she called it the “Flying Laboratory” — that she piloted during her ill-fated flight.

After her disappearance, Earhart’s husband, George Palmer Putnam, offered a collection of her personal papers to the university because of her love for Purdue and Putnam’s appreciation of its support.

The Amelia Earhart Collection is housed at Purdue Archives and Special Collections. Featuring nearly 5,000 items, from her flight helmet and goggles to her pilot’s license and will, it is the world’s largest collection of Earhart-related papers, memorabilia and artifacts.

LILLIAN GILBRETH

When describing Gilbreth’s place in history, Klink prefers to wait until the very end to mention the most common way she’s known to the general public. Leading with it feels … cheap.

Klink would much rather share how Gilbreth became the nation’s first female engineering professor when she accepted a position with Purdue’s School of Mechanical Engineering in 1935. She became a full professor five years later and contributed to the departments of industrial engineering, industrial psychology and home economics, and she also consulted on careers for women through Stratton’s dean’s office.

Klink would rather discuss Gilbreth’s landmark time-and-motion studies first conducted alongside her husband, Frank, and then well after Frank’s death from a heart attack at age 55.

She’d prefer to share that Gilbreth was a pioneer in the field of industrial management, injecting psychological considerations into management theory and thereby demonstrating tactics that companies could employ to become more productive and efficient.

But if all else fails and the other party is still unaware of Gilbreth’s story?

“If they’re still looking out into the stars like they don’t understand, I’ll say, ‘Or have you heard of “Cheaper by the Dozen”?’” Klink says with a chuckle.

That’s right; not only was Gilbreth “America’s First Lady of Engineering,” but her family was the subject of two semi-autobiographical books written by children Frank Jr. and Ernestine — “Cheaper by the Dozen” and “Belles on Their Toes” — that shared what it was like growing up in a household with 12 kids and two parents who test their efficiency theories at home. Both books were turned into movies in the 1950s, and “Cheaper by the Dozen” was remade in 2003 with Steve Martin and Bonnie Hunt in the lead roles.

“To be that organized and have that many kids, the woman had a lot of energy,” Klink says. “She had a lot of drive. She knit and crocheted and made lace and walked so many steps a day. She was just an amazing person. Obviously, she used her time-and-motion studies on her own personal life.”

(Lillian Gilbreth) was just an amazing person. Obviously, she used her time-and-motion studies on her own personal life.

Angie Klink (BA communication ’81)

Purdue historian and author

In 2018, Purdue’s College of Engineering introduced the Gilbreth Postdoctoral Fellowship program to prepare recent PhD recipients for careers in engineering academia through interdisciplinary research, training and professional development.

MARY MATTHEWS

Matthews and her adopted mother, Virginia Meredith, are both important figures in Purdue’s history.

Meredith, known as the “Queen of American Agriculture” in the late 19th century, became the first woman appointed to Purdue’s Board of Trustees in 1921. The university’s Meredith Hall is named in her honor.

Her adopted daughter became the first female academic dean at Purdue in 1926 when she launched the School of Home Economics. She opened the first nursery school in the state of Indiana that same year at Purdue.

Matthews’ commitment to sharing the latest home science with women at Purdue and beyond defined her tenure at the university.

Klink’s book “Divided Paths, Common Ground” shares the story of Matthews and Lella Gaddis, whom Matthews hired to lead Purdue’s home economics Extension service and share knowledge about nutrition and food safety with rural women who had no connection to a college campus.

“A lot of these things were vital for public health,” Klink says. “Mary was teaching it here on campus and Lella was taking it out to the countryside. A lot of the women were isolated on farms and they just learned from what ancestors handed down, and they’d been learning things that aren’t benefiting society at that time healthwise and efficiencywise.”

A lot of the women were isolated on farms and they just learned from what ancestors handed down, and they’d been learning things that aren’t benefiting society at that time healthwise and efficiencywise.

Angie Klink (BA communication ’81)

Purdue historian and author

After arriving at Purdue in 1910 as an Extension home economics instructor, two years later Matthews became head of the Department of Household Economics in the School of Science with 50 students under her guidance. By the time she became founding dean of the School of Home Economics in 1926, the program had 369 undergraduate students spread across five departments.

When Matthews retired as dean in 1952, Purdue offered 150 courses in home economics (it had four in 1926) and boasted the second-largest enrollment of any U.S. home economics school.

Constructed in 1923, the original home economics building now known as Matthews Hall was named in her honor in 1976.

HELEN SCHLEMAN

One could reasonably argue that no individual did more for Purdue women than Schleman (MS liberal arts ’34).

She remains influential to many Boilermakers with whom she interacted across the generations, even if she didn’t garner the national celebrity of an Earhart or Stratton — her close friend and mentor who brought Schleman aboard as her right-hand woman while leading the women’s reserve of the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II. However, Schleman’s persistence — and absolute refusal to accept the status quo — during a 20-year stint as Purdue’s dean of women (1947-68), and later in retirement, created a legacy that is unmatched in the university’s history.

As a Purdue administrator in the 1950s and ’60s, Schleman sometimes faced pushback within university circles for staunch feminism that conflicted with the conservatism of postwar America. But she was the driving force behind numerous activities that chipped away at the traditional gender dynamics in place at Purdue and across society in that era.

“She was always ahead of her time,” says Klink, whose book “The Deans’ Bible” details the special bond that existed between Schleman and four other Purdue deans: Stratton, Barbara Cook, Betty Nelson and Beverley Stone. “She said she was born too early, but really she wasn’t. She was born saying and doing these things when it was really, really needed to try to wake people up.”

Schleman won out in a long fight to eliminate Purdue’s curfew for female students, making Purdue the first Big Ten university and one of the first in the nation to do so. She also led the fight for equal hiring, pay and benefits for Purdue’s female faculty and administrators, and she was ultimately successful in a court case that ensured participants in the university retirement plan would not be discriminated against on the basis of gender.

While serving as dean of women, Schleman invited all incoming freshman female students to her office, where she would offer an individual welcome and encourage them to complete a degree that would allow them to be self-sufficient if necessary.

(Helen Schleman) said she was born too early, but really she wasn’t. She was born saying and doing these things when it was really, really needed to try to wake people up.

Angie Klink (BA communication ’81)

Purdue historian and author

“She’d say, ‘You need your degree. Because what if, God forbid, your husband dies, or you get a divorce? You don’t think you are now, but what if that happens? You need money to fall back on, a “Go to Hell Fund,” because of those catastrophes that can happen,’” Klink says. “That was unheard of in the day, to ask a woman that, or even to expect a woman to really have that little nest egg of her own put away for emergencies.”

In 1968, Schleman founded and led Span Plan, which supports undergraduate nontraditional students — such as parents who delayed enrolling in college until after their children started school — as they enter the world of higher education. The program remains active at Purdue to this day.

DOROTHY STRATTON

During her nine-year stint (1933-42) as Purdue’s first full-time dean of women, Stratton saw women’s enrollment nearly triple. This was in part due to her efforts to create opportunities for Purdue women.

She managed construction of residence halls for women, pushed for women’s restrooms in all campus buildings and created a women’s employment placement center. She also attempted to implement a liberal arts-style curriculum geared toward women that would provide an alternative to studying home economics.

However, her activities away from Purdue provide the first several paragraphs of her biography as a national historical figure.

After America entered World War II, Stratton joined the U.S. Naval Women’s Reserve with encouragement from her dear friend Gilbreth, whom she called “Dr. G.” When the U.S. government created the women’s reserve of the Coast Guard, Stratton was transferred to become the program’s first director and the first woman commissioned as an officer in the Coast Guard.

“They contacted her and said, ‘We need a woman to head up the Reserve of the Coast Guard, and you’re going to do it,’ maybe because she’d been dean of women,” Klink says. “She was very courageous and smart.”

Stratton led the U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserve, which she named SPAR (an acronym for the Coast Guard fighting motto “Semper Paratus, Always Ready”), through the end of the war and eventually achieved the rank of captain. Responsible for recruiting, training and utilizing women in SPAR — which was racially integrated from the beginning, not a military norm at the time — Stratton led more than 10,000 women who enlisted during the war. In 1946, she was awarded the Legion of Merit for her contributions to women in the military.

One of (Dorothy Stratton’s) adages she often repeated was ‘To be interesting, do interesting things.’ Well, she did, fearlessly.

Angie Klink (BA communication ’81)

Purdue historian and author

In 2008, the Coast Guard named a national security cutter the USCGC Stratton in her honor. It was the first national security cutter to be named after a woman. First Lady Michelle Obama christened the ship in 2010, saying, “As a woman, and as a mother of two daughters, as an American, I stand in awe of her life of service. And after all these years later, whether you’re a woman or a man, Coast Guard or another service, whether you’re military or civilian, every American can be inspired by her example.”

In 2023, Purdue added Stratton’s name to its Veteran and Military Success Center.

Stratton’s societal contributions didn’t end when she left the military. In 1947, she became the first director of personnel at the International Monetary Fund. She spent three years in that position before serving for the next decade as executive director of the Girl Scouts. Stratton was also the United Nations representative of the International Federation of University Women (now known as Graduate Women International) and served on the President’s Commission on Employment of the Handicapped.

In the 1980s, Stratton moved back to West Lafayette and shared a home with Schleman, her dear friend of more than 50 years. She died in 2006 at age 107.

“One of her adages she often repeated was ‘To be interesting, do interesting things,’” Klink says. “Well, she did, fearlessly.”

It’s important to write these stories down, because other generations have no idea whose shoulders they’re standing on.

Angie Klink (BA communication ’81)

Purdue historian and author

Bringing a treasured Indy 500 tradition to the Purdue Grand Prix

Mimicking Indy’s iconic Yard of Bricks, Purdue’s track now features a row of original IMS bricks at the start/finish line

Out of the hundreds of racetracks in the U.S., only two have racing surfaces that include original bricks from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

One, of course, is IMS, where the start/finish line features the legendary Yard of Bricks — the only portion of the brick-covered track installed in 1909 that remains part of the current racing surface. These bricks hold such a special place in racing lore that winning drivers traditionally bend down to kiss them after a successful run at The Brickyard.

The other is the Purdue Grand Prix track, thanks to a generous donation by Doug Boles, president of IMS and IndyCar, and three Boilermaker alumni who facilitated the brick donation and installation last fall.

“How cool is that, to be the only other track to have the original Culver brick in it?” asks Al Wurster (BS building construction technology ’85), a Grand Prix alum who first approached Boles with the idea three years ago. “The rich history of the Motor Speedway and what that brings to Purdue is pretty cool.”

Luckily, Boles was receptive to Wurster’s pitch, agreeing to donate some of the track’s few remaining original bricks to form the start/finish line at the Grand Prix track. On March 12, Boles attended a ceremony where representatives of the Purdue Grand Prix Foundation installed the final IMS brick in the row.

“For me, this is just a way to remind people that the Indy 500 doesn’t exist without Purdue University and the people that have graduated from Purdue University,” Boles says, citing the many historical connections between Purdue and one of the world’s most famous auto races. “This is just one more way to say we belong together, Purdue and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.”

Although they are no longer visible except along the Yard of Bricks, the vast majority of the original 1909 bricks are still in place on the IMS track. They’re buried beneath several layers of newer racing surface from when the track was paved with asphalt in 1961 and resurfaced numerous times since then.

The bricks now at Purdue came from the small stash that IMS keeps in storage, adding a powerful new link between the Grand Prix track and its big brother in Indianapolis.

For me, this is just a way to remind people that the Indy 500 doesn’t exist without Purdue University and the people that have graduated from Purdue University.

Doug Boles

President, Indianapolis Motor Speedway and IndyCar

Old rivals reunite

Way back in the 1981 Purdue Grand Prix, race leader Bill Shumaker’s go-kart collided with Dave Fuhrman’s during a pass attempt, launching Shumaker’s kart end over end five times before it crashed into the fence that separated the spectators from the track. Fuhrman went on to win the race, while Shumaker was fortunate to be OK following one of the more violent Grand Prix wrecks that had occurred to that point.

“During the ’81 race, he was faster and I was luckier,” recalls Fuhrman (BS aviation technology ’81), now president of the Purdue Grand Prix Alumni Organization. “His kart tumbled into the crowd, and he was out of the race at that point. That was the defining moment of the race, when we came together, and he couldn’t continue, and I did.”

On an October afternoon more than four decades later, the former racing rivals found themselves side by side on the Purdue track once more. Only this time, they were creating a much happier form of race history, helping to install a single row of IMS bricks across the track at the start/finish line — leaving one central space for the final brick that was installed March 12.

Fuhrman first had the idea several years ago when the alumni organization raised funds to have the Grand Prix track resurfaced.

“I thought it would be a perfect opportunity with the new pavement down to try to request that the Speedway provide some pedigree bricks to put at the Purdue start/finish line to replicate the Speedway’s,” he says.

So he took the idea to Wurster, who served as chair of the 500 Festival in 2006 and still maintains connections with Boles, the iconic racetrack’s head honcho.

Fuhrman also approached Shumaker (BS building construction technology ’81) and his brother John (the 1983 Grand Prix winner), owners of Globe Asphalt Paving Co. in Indianapolis, about lending their expertise to the project.

“They were the people that originally paved the new Grand Prix track that we’re on now,” Fuhrman says. “Over the years, they’ve also been instrumental in repairing damage and things like that on the track. Bill was all excited and volunteered and donated the materials and the expertise and the equipment to actually lay the bricks into the track.”

Adds Shumaker, “They reached out and asked if I’d be willing to do it. All along I said I would and that ‘if you get the bricks, I’ll put them in.’”

Sure enough, they did. But it was a process that required patience.

Retrieving the bricks

Believe it or not, the guy who oversees the world’s largest sports venue has a jam-packed calendar.

When Wurster first brought the brick donation idea to Boles a few years ago, the racetrack’s president agreed to help. However, like a rainy practice day in May, there were several starts and restarts before they were finally able to find a time where Boles could meet Wurster at the secret bunker where IMS keeps its stash of remaining original bricks.

Because of the historic (and monetary) value of the room’s contents, only a select few have been granted access.

“I’ve been told by Mr. Boles that that location is undisclosed,” Wurster says with a chuckle. “As well as how many bricks they have. I can’t disclose that either.”

In 1909, the track owner hired Wabash Clay Co. in Veedersburg, Indiana, to install 3.2 million bricks — enough to cover the entire 2.5-mile oval. Wabash’s bricks, known as “Culver blocks” after patent holder R.D. Culver, made up roughly 90% of the bricks installed at IMS. The remaining bricks came from subcontractors that Wabash needed to help fulfill the IMS order, which took 63 days to install.

All the bricks installed at Purdue are Culver pavers, some of which were unusually shaped or warped — likely because of the combination of their age and the inconsistency of the brickmaking process in the early 20th century. Wurster grabbed a couple extra just to make sure they had enough that would lie flat across the start/finish line.

“In today’s age, when placing bricks on any project, you expect all the bricks to be exactly the same size,” Shumaker says. “But these things definitely aren’t. I’m not sure when they were made — turn of the century or something back then — but we had to leave a little more room for them in the concrete brick bed. They may not sit perfectly flat across the top, but we tried to average everything out so when cars go across them, it’s still pretty smooth.”

Fuhrman selected a special brick out of the batch to sit at the center of the row. Because of the diamond-cut surface on the brick, he believes it once fulfilled an important purpose at IMS.

“As far as I know, the only place at the Speedway that the brick had diamond cut was at the start/finish line,” Fuhrman says, “so I think it has an actual pedigree to the start/finish line at the Speedway.”

Extending the Purdue-IMS partnership

Purdue’s relationship with IMS and its signature race, the Indianapolis 500, stretches back more than a century.

The Purdue “All-American” Marching Band has been the race’s official band since 1919, known for performing “Back Home Again in Indiana” moments before the race begins each year. The garage is well stocked with Purdue engineers who learned their trade at the only ABET-accredited motorsports engineering program in the country. And there are countless other Boilermakers who work behind the scenes to make “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing” a success.

The Grand Prix’s slogan even mimics that of the Indy 500.

“When you talk about synergies, (the Grand Prix is) allowed to use the term ‘The Greatest Spectacle in College Racing’ for our race,” Wurster says. “So that tells you how deep that goes, in my opinion, with the Motor Speedway.”

Purdue student Wil Rohrbach, president of Purdue Grand Prix Foundation, believes the timing of the Grand Prix race each April helps it complement the monthlong festivities that take place in May for the 500.

“It is pretty unique to Indiana to see people connected by racing and remembering where they’re from, their hometown roots,” says Rohrbach, a junior from Fort Wayne, Indiana, majoring in agricultural economics. “A lot of people go to the race at Indy every single year. And then especially if they grew up near Purdue, they would come here first in April and then go down to the Speedway in May. I view it like we’re an appetizer to the big race at the Speedway.”

Now, because of the behind-the-scenes work by three Grand Prix alums, the connection between the appetizer and main course is further blended — adding a new layer of tradition for future Boilermakers who will also view the Grand Prix as one of the highlights of their college experience.

“It’s an affirmation that the Purdue race does have significance in the state,” Fuhrman says. “Obviously, the size is significantly different, but the emotions and the competitiveness are very similar to the 500. Our state has a lot of iconic places, and the Speedway is at the top of that list. And if the Purdue Grand Prix can be part of that, even better.”

How cool is that, to be the only other track to have the original Culver brick in it? The rich history of the (Indianapolis) Motor Speedway and what that brings to Purdue is pretty cool.

Al Wurster (BS building construction technology ’85)

Purdue Grand Prix alum and chair of the 500 Festival in 2006

International stage for Purdue’s Krivokapic

Purdue men’s tennis star Aleksa Krivokapic competes in China for his native Montenegro

The tears welled up as the music played. Aleksa Krivokapic couldn’t hold back as the national anthem of Montenegro — his national anthem — played during the Davis Cup in January.

“It was special,” he says. “It made me feel proud.”

Krivokapic takes a deep sigh and looks at the ceiling as he gathers his thoughts about one of the most significant events of his life.

Who can blame him for getting emotional?

Krivokapic grew up in Montenegro, swatting tennis balls against anything, dreaming of being paid to play tennis one day. With each batted ball, a young, scrawny Krivokapic got better. And better. Good enough to the point where the notion of one day being a pro didn’t seem out of reach. The dream could be reality … maybe.

Playing in the Davis Cup gave him a taste of facing off vs. pros. For now, Krivokapic polishes his trade at Purdue.

“I ended up deciding to play college tennis instead of going pro,” he says. “We didn’t have the finances to go pro.”

After winning the Big Ten Individual Championship in November, he has earned his keep as Purdue’s No. 1 singles player, forging a 4-3 record thus far. But his junket to China to represent his homeland in the Davis Cup still resonates.

What a thrill.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “To be there and to compete. It was an experience I never will forget.”

While in China, Krivokapic got to play against top competition, as Krivokapic took part in singles and doubles.

Montenegro came up short and failed to advance. But that wasn’t the point. The big takeaway was the opportunity to play on that stage against that level of competition. It’s about getting better.

“It was tough,” he says.

Krivokapic shrugs his narrow shoulders and leans against a wall inside Purdue’s Schwartz Tennis Center. Fellow tennis players whirl by to workouts on a frigid February morning in West Lafayette.

“We battled hard, and I got confidence playing against some good players, enough confidence to believe I could one day play professionally,” he says.

The pros can wait. Krivokapic still has runway ahead of him at Purdue. He is just a junior, still authoring his story in West Lafayette. How will it end?

“I am enjoying my time here,” he says.

It’s a long way from mid-north Indiana to Krivokapic’s home in Podgorica, Montenegro, the nation’s capital and largest city that teems with over 100,000.

Across the ocean, Krivokapic’s father is a television producer, while his mother is a lawyer for a bank. Young Krivokapic was a thin whip-of-a-kid living in a nation that adores soccer, water polo, handball, tennis and basketball. Oh, how it loves basketball.

Krivokapic was splitting his time between tennis and basketball when, as a 10-year-old, his father sat him down for a talk. It was time to choose a sport and path: What’s it gonna be, Aleksa? Basketball? Tennis?

“My father guided me to continue with tennis,” he said.

But Krivokapic still wonders … what if? What if he had gone with basketball? When the 6-foot-5 Krivokapic closes his eyes, he can envision himself draining 3-pointers, euro-stepping in the lane and finishing with a reverse layup.

“Yes, I do think about that,” Krivokapic says, flashing a toothy grin. “I’m still pretty good when I play.”

What team couldn’t use a 6-5 wing shooter with an impossibly long wingspan?

Exactly.

But, Krivokapic’s hoop dreams have become hardcourt dreams. And he hasn’t looked back.

“I have no regrets,” he says.

It’s a long way from Montenegro, a country in southeastern Europe on the Balkan Peninsula, to the United States. He misses his family in Montenegro, across the Adriatic Sea from Italy. Oh, how he misses their embrace.

And when Krivokapic feels especially sentimental, he yearns for some of his grandmother’s cooking. Any go-to dish “Baba” serves is anchored by potatoes and meat.

“Whenever I am home, Baba asks me what I want to eat. ‘What do you want?’ she says. “I love her. She takes good care of me.”

By the looks of Krivokapic, he could use more of Baba’s home-cooking to thicken up his stretched-out carriage.

“Look at me,” he says with a soft Montenegro accent, holding his arms up.

But Krivokapic needs to remain nimble and able to cover the entire court with a game highlighted by a strong serve that caught the attention of talent scouts and recruiters.

“Those are things I do well,” he says. “Those are the strong points for me.”

Those traits have taken Krivokapic a long way. He first touched down in America in Chicago at DePaul, where he spent his 2023 freshman season.

“I didn’t take an official visit,” he says. “So, the first time I ever stepped in America, it was when I got off a plane in Chicago and went to DePaul. There are a lot of distractions in Chicago.”

Krivokapic smiles. It’s something he does often.

“He’s a very nice guy,” says Purdue tennis coach Geoff Young. “He’s got a good sense of humor, and I think he’s fun to have on the team. He brings a lot of life to the locker room; he’s funny, and he really wants to be a good tennis player.

“He’s been very open to learning and trying some new things, and it’s really helped him improve, even in the short time he’s been here at Purdue.”

But his growth hasn’t just been individual – his impact on the team has been just as important. “Aleksa is a kind of teammate who you can always count on,” says teammate and freshman rising star Maj Premzl. “He leads by example with his work ethic end competitiveness and pushes everyone to be better. Off the court he is supportive and brings great energy making sure we stay motivated and stay connected as a team.”

After a year with the Blue Demons that saw Krivokapic earn Big East Freshman of the Year honors after going 10-4 in singles play and 4-0 in Big East action, he entered the transfer portal and moved on to Purdue, where he has been the last two years.

“I was looking to develop my game and play at a higher level,” he says. “Purdue has been a good choice for me. I like it here.”

Krivokapic’s game is highlighted by his aggressive style, which often involves him attacking and being the aggressor at the net.

“He’s got a very good serve, and he’s very tall, and he has good touch, good feel for the ball,” Young says. “He’s pretty good on the volley, but really good at the net. He’s good on ground strokes, as well.

“But I think he’s learning that to maximize this game, he has to move forward as much as possible and finish the points at the net.”

Krivokapic’s Purdue debut last year was muted by an abdominal injury that limited him, but he still managed to notch seven wins across the fall and spring seasons before succumbing.

“That was tough,” says Krivokapic, pointing to his midsection. “But I am OK now.”

Is he ever. Krivokapic is the anchor of a surging Boilermaker men’s tennis program that will get tested when it treks to southern California this weekend to take on USC and UCLA in the Big Ten opener.

Krivokapic folds his arms, nodding hello to a passerby as he gathers his thoughts.

“The Davis Cup was an amazing experience,” he says. “It is a very prestigious event. It’s like the World Cup for soccer. To get a chance to compete in it was special. We didn’t do well as a nation but battled and played hard.”

Back home in Montenegro, Krivokapic’s family watched on TV. Even Baba.

“Pretty neat,” he says.

“When they raised our flag and played the anthem, it made me so proud of my country and where I am from. It was such an honor to be on that stage and to play and compete on that level. I’ll never forget it.”

Written by Tom Dienhart

The making of Mackey magic

It takes careful planning and extensive teamwork to create a memorable fan experience at Mackey Arena

It mirrors Coach Matt Painter’s renowned men’s basketball program.

The behind-the-scenes crew that makes the Mackey Arena experience unique for Purdue fans through its thoughtful game presentation follows the exact credo of the 20-year Boilermaker coach: Build a great team with experience and youth, trust one another, dare to be creative, communicate and, most of all, DO YOUR JOB.

“You are surrounded by creative and innovative people that do their jobs at the highest level,” says Marlee Thomas, game host for the past four seasons. “It makes you always want to be at your best.”

Being at one’s best is an everyday task. And for the award-winning team of dozens of video, audio, musical and graphical talents that help make Purdue’s 58-year-old facility vibrant and fresh, it is a challenge accepted with an eye for constant improvement.

And there’s more.

“We have learned to be the owner of our space,” says Andrew Stein, director of photography services, who travels with videographer Andrew Bay to all road games. “Trust is a big word that helps us perform as a team.”

Painter is a master delegator

Much like with his coaching staff, Painter is a delegator. He has no interest in delving into the details of the marketing and presentation of Boiler Ball.

“Coach Painter doesn’t want to be involved in the minutiae of what we do,” Bay says. “He knows it matters. He sees the value. For example, he is comfortable letting me in the huddle to shoot during a crucial timeout, letting me do my job while trusting I will always have the best interests of his program at heart.”

As Purdue’s associate athletics director in charge of marketing and fan experience, Chris Peludat is the ringleader of what the Mackey faithful see, hear and feel. He says Painter doesn’t say much about the job his crew does, but when he does, it makes an impact.

“There’s a recent quote that says it all,” Peludat says. “He said that in the past 10 years, our team has been able to make every game in Mackey at a level like only big games in the past used to be. The coach knows that is what we’re shooting for and how we base every decision on how we proceed.”

And the coach couldn’t be more spot on.

Like Painter’s team, it’s all about the process for the game-day folks. Director of men’s basketball operations and administration Elliot Bloom, who is attached at the hip to Painter, has been integral in setting the vision and tone for the game-day experience. A Purdue graduate, Bloom saw the best of the best men’s hoops environs with stints at Kansas and Duke before returning to Purdue 23 years ago, spending the first seven in a sports information role. Bloom knows it when he sees it and has seen it from the Boilermaker bench for the past 16 years.

We never take for granted that attending games is a time and financial commitment for our fans.

elliot bloom director of basketball administration and operations

“Winning at an elite level is the most important thing,” Bloom says, “But nearly as crucial is creating an atmosphere where fear of missing out for people is real.”

“You have to create magic in that building and do some things that people think, ‘Do I want to go to that Wednesday game that tips at 8:30 p.m.?’ When they pick up social media the next morning, we want them to say, ‘I knew I should have gone. What was I thinking?’”