Boilermakers explore ‘Mars’ on Earth

Purdue students wearing spacesuit simulators explore the area surrounding the Mars Desert Research Station in Hanksville, Utah.

At the Mars Desert Research Station, Purdue crews live and work as if they are truly inhabiting the red planet.

Nestled between Capitol Reef and Canyonlands national parks is an alien landscape so filled with otherworldly rock formations and colorful hills, you may think you are on another planet.

And for crews of Purdue analog astronauts, you would be exactly right.

The Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS), located near Hanksville, Utah, has served as Mars on Earth for Purdue researchers since the first all-Boilermaker mission launched in 2017.

“Geologically, it’s pretty much a dream location,” says Adriana Brown, commander of MDRS Crew 289.

“It’s one of the most realistic analog Mars locations on Earth,” agrees Cesare Guariniello, commander of MDRS Crew 288.

Established in 2001 and owned and operated by the Mars Society, MDRS supports Earth-based research in pursuit of the technology and operations required for off-world human space exploration.

“Analog” astronauts assume the role of an astronaut while they are at MDRS. They conduct research and go about day-to-day life as if they are actually on Mars.

Putting learning into practice

“Many people come to Purdue because of its reputation as the Cradle of Astronauts,” says Kshitij Mall, a postdoctoral research associate and one of the primary architects behind Purdue’s successful trips to MDRS. “They come to Purdue because either they want to be astronauts or they want to be around astronauts. An important aspect of educating these people is to prepare them to go on a real mission. But you can’t do everything in a classroom. At Purdue, you have this unique opportunity to put learning into practice.”

Fieldwork opportunities at MDRS are rare. Usually, no more than 15 groups can be accommodated each year. Through persistence and excellence, Purdue secured a fixed annual rotation at MDRS and even earned the chance to send an unprecedented two crews to Utah in one season.

A global victory. A $10,000 cash prize. And an incredible opportunity.

The relationship between Purdue and the Mars Society started with teamwork, innovation and a healthy dose of competition.

Mall, a PhD student in Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AAE) at the time, was conducting research in Japan as part of an AAE and Global Engineering exchange program when he met Shota Iino. Iino, a then-graduate student at Keio University, invited Mall to form an international team to compete in the Mars Society International Student Design competition.

Team KANAU was born, and it included Mall and Iino as well as four other Purdue participants and several Japanese students. The competition required teams to design a two-person Mars flyby mission. After presenting its design to a team of six judges, Team KANAU emerged victorious, capturing the $10,000 prize.

Inspired by the camaraderie of the Mars Society competition and informed by the analog Mars exploration experiences of several individual Purdue alums, Mall recruited an all-Purdue crew to apply for one of the highly coveted fieldwork spots at MDRS.

“It was like running a startup company,” Mall says. “The mission requires crew members to fill specific roles, such as commander, health and safety officer, crew engineer, crew geologist and more. For Purdue’s first mission to MDRS, we enlisted people who are passionate about Mars as well as smart, capable and disciplined.”

Again and again and again

The first MDRS Purdue crew set the pattern for the groups that followed: perform well, make a good impression, get invited back.

Purdue research scientist Guariniello, who is readying to embark on his sixth Purdue mission to MDRS, explains: “There are so few openings at MDRS and so many people competing for the opportunity, but Purdue is invited back year after year because we consistently perform so well. Our Mars Society partners always tell us that our research and our logistics are of the highest quality.”

The work ethic and team spirit of Purdue crews play a large role in MDRS successes, too. “Crew members see something needs to be done, and they do it,” Guariniello says.

He adds, “We want to test different aspects of space exploration, and we want to work as a team in a location where nobody is there to help you out. We are encountering the same challenges and conditions emotionally and physically that you would on an actual mission to Mars. If you get in trouble, you learn how to take care of the situations that arise yourself.”

In applying to the program, crew members propose two or three different research projects they would like to pursue. But they are also expected to help with the research projects of other crew members. A crew journalist may also help a crew scientist take care of plants in the GreenHab. A crew geologist may also serve as the health and safety officer, which requires knowledge of CPR and first aid.

Rather than being intimidated by these responsibilities, Purdue crew members are excited. More than 50 people applied this year for the highly sought-after crew spots on the next Purdue mission to MDRS. In previous years, Mall and Guariniello have received as many as 100 applications.

Purdue is invited back year after year because we consistently perform so well. Our Mars Society partners always tell us that our research and our logistics are of the highest quality.

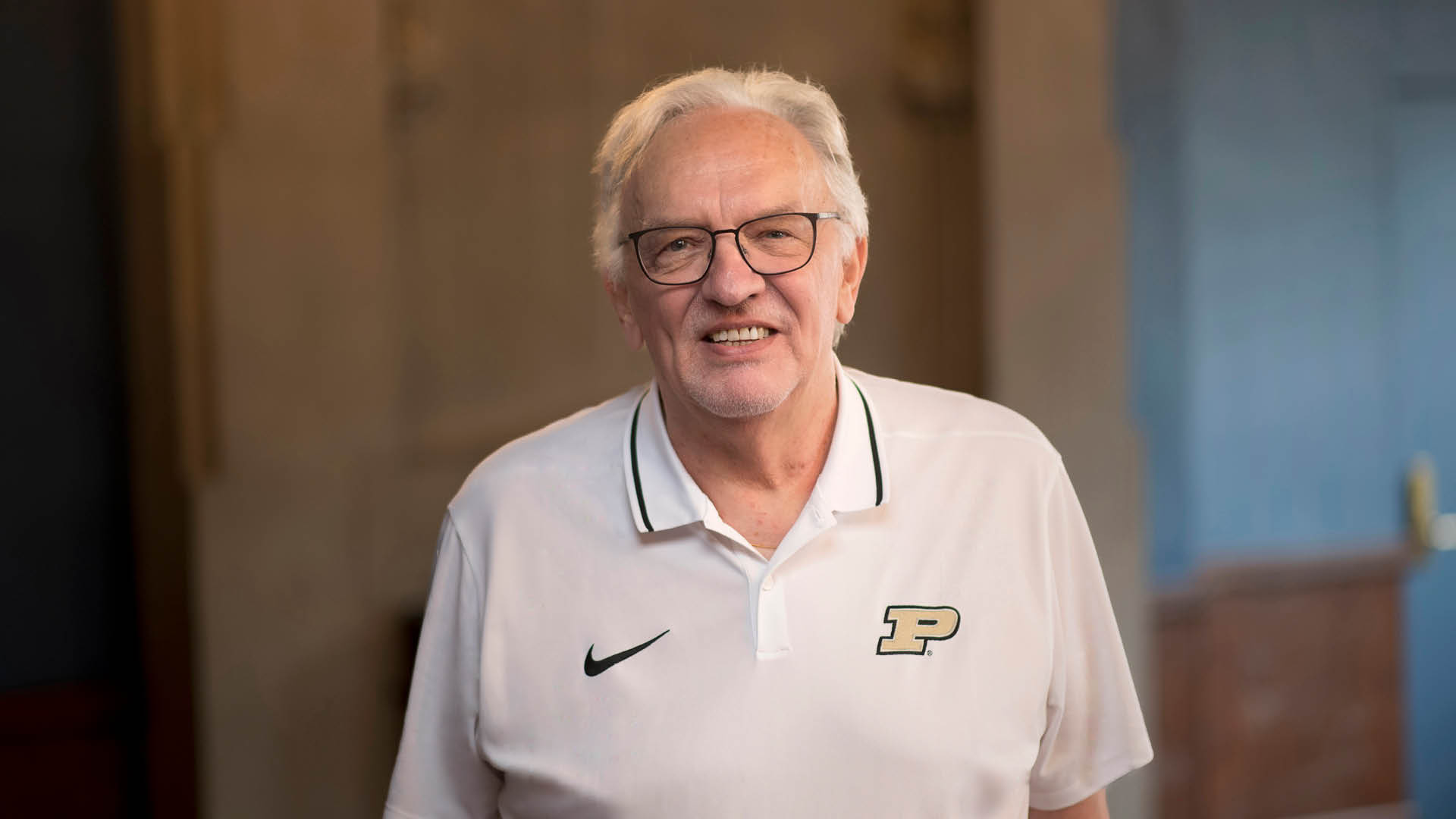

Cesare Guariniello Purdue research scientist

Two weeks. Seven analog astronauts. Four hundred gallons of water.

“We always point out that being an analog astronaut is not pretend. We don’t go to Utah to play,” Guariniello says. “This is a realistic mission, where people are in close quarters and must live together and solve challenges together. MDRS is a place to test things that would be useful for future human explorers on Mars, especially social interactions and conducting research in a remote, limited environment.”

For two weeks, Purdue analog astronauts live and work in “the Hab,” a two-story circular structure 8 meters in diameter. The Hab is stocked with limited supplies, comparable to those which astronauts would have available. Four hundred gallons of water, for drinking and cleaning, must last seven crew members two weeks.

The moment the simulation starts, crew members are confined to the Hab and the surrounding MDRS campus, which includes a GreenHab, two observatories, a science dome, and a repair and maintenance module. Crews can’t just open the front door and go outside. They must use airlocks to exit the Hab and must wear flight suits, helmets and heavy air packs while conducting research outside the MDRS campus.

Even the timing of Purdue’s missions to MDRS, during the winter break, simulates the sacrifices that astronauts make in being away from loved ones during the holidays.

“It increases that sense of isolation from Earth a bit. But I will also say that it really allows the team to bond when we’re there together,” says Brown, who served as crew geologist last year.

“I interacted with people from different departments and from all over the world — people who I had not previously encountered in my four years at Purdue. And I have stayed friends with many of them.”

When are you ever going to get this chance again?

Conducting research in the field is a significant component of the MDRS experience. “It’s truly an exercise in building a project from the ground up. You come up with an idea. You look for funding sources. You plan out the details and the equipment you will need, and then you execute and write about it,” Brown says.

Research at MDRS must be useful for Mars exploration and something that can be done only in an analog environment. So crew members cannot do something at MDRS that can be done in a lab. Research also relies on using available materials. Missions to Mars will be constrained by weight and unable to carry every needed resource from Earth.

Brown adds, “It’s a huge opportunity for people who work in these fields. It can be difficult to do fieldwork in this area of study. And so it’s a unique opportunity, especially for students who study habitats in extreme environments or in human space exploration.”

Previous research projects have included evaluating human dynamics under stressful situations, performing a noninvasive search for water and mapping radiation. Participants apply to join the crew with their own research projects, but by the time the mission solidifies, projects become consolidated. Crew members may not be working on exactly what they originally proposed, but they are working on something for the greater good of the team and of the mission.

Brown says, “My experience with MDRS really had me level up as a researcher. What it really came down to for me is: When are you ever going to get this chance again?”

What next?

After earning her Bachelor of Science in environmental geoscience from Purdue last December, Brown pursued graduate work. She credits her MDRS experience as contributing toward her acceptance to the PhD in Earth and Environmental Sciences program at the University of Michigan.

“Professionally, it was so helpful to write about the MDRS experience,” she says. “I was asked about it in nearly every interview, and I have presented on it with Kshitij at American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics ASCEND 2023. MDRS stands out as a unique experience.”

Other Purdue MDRS alumni have gone on to secure internships and jobs at places like Blue Origin and NASA.

Purdue’s MDRS efforts are currently pursued independently, but there are conversations about expanding to include a certificate program or even adding an analog astronautics class that will allow students who can’t make it to MDRS to still prepare for experiencing an analog environment.

Purdue will continue to take small steps toward the next giant leap of one day sending humans to Mars.